Intangible assets are key to modern economic activity – but how should we value them?

Counting investment has long been one of the key ways economists and accountants make sense of growth, wealth and capital assets. But whereas the majority of investment in these assets were once tangible, such as buildings, plants and vehicles, intangible assets, including software, R&D and design are now a cornerstone of the economy.

Figures show the volume of annual investments in “intellectual property products”, including titles for patents, trademarks and designs, which help organisations protect and value their IP intangibles, has increased by a staggering 87 per cent in the European Union (EU) in the last 20 years. Meanwhile tangible investments increased by just 30 per cent, according to a recent study conducted by the European Commission.

These “intellectual property products”, such as R&D, software and artistic originals, are only part of what companies spend on intangibles. They also invest in other “knowledge” assets such as design, market research, training and new business processes. As a result, major efforts are being made to incorporate a broadening range of intangibles into national accounts. But despite their growing importance, the challenge of assigning value to non-physical assets still looms large.

The problem with intangibles

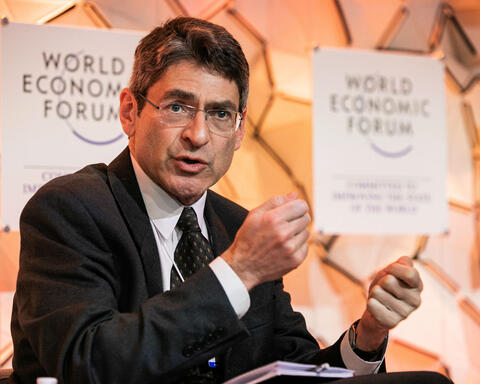

Through his research, Professor Jonathan Haskel, Chair in Economics at Imperial Business School and a member of the Monetary Policy Committee at the Bank of England, has instigated significant changes to address some of the issues faced by those responsible for valuing intangible assets.

Among these is the issue of protection: while firms can exclude competitors from using their buildings, the same does not apply to their designs. This is particularly evident in the smartphone market, with almost all mobile handsets now a variation on the iPhone. Another is that intangible investment cannot usually be recovered and is therefore considered a “sunk cost”. For example, Nokia can sell its building but not its software.

More positively – although still problematic for the accountant – intangibles can often be combined with other non-physical assets to increase their value. For example, combine the Harry Potter script, CGI software and theatrical design, and you have a very lucrative film series.

Additionally, there is the problem of transparency: if a company secretly conducts an R&D project, then any results will not be counted among its assets.

Jonathan’s work on intangibles over the past decade or more has been very valuable to the ONS

With so much potential – and so many possible eventualities – it can be hard to pin down how much an intangible asset is worth.

Meanwhile, guidance on national accounting advises including some intangibles, such as R&D, software and databases, entertainment, literary and artistic originals, as capital investment, but not others, including brands, organisational structures and human capital.

The problem is that not counting certain intangibles has a serious knock-on effect, potentially “leading to a reduced understanding of the economy, especially as it becomes increasingly service-based", according to Jonathan Athow, Deputy National Statistician at the Office of National Statistics (ONS).

Professor Haskel’s work, including the best-selling book Capitalism without Capital, recommended by Bill Gates and named one of the best books of 2017 by both The Economist and the Financial Times, has shown that better measurement methods are crucial to resolving these complex problems.

Changing the method

Taking a real-life example, according to ONS figures, investment in artistic originals for TV, radio, music and film – key areas of the country’s creative economy – was believed to have remained consistent between 2009 and 2016 all because of a lack of reliable data.

In an attempt to correct this, the Independent Review of Economic Statistics carried out by Professor Sir Charles Bean in 2016 referenced Professor Haskel’s work, calling for the UK Office of National Statistics to “continue to develop the measurement of intangibles, including through close collaboration with academics and other experts”.

Based on Professor Haskel’s research, improved measurement methods, which considered production costs, royalties and film-level revenue, and ownership data, were implemented.

This has led to significant developments in the valuations of intangibles, with the ONS including revised data on the value of investment in entertainment, literary and artistic originals in the 2013 National Accounts, increasing GDP forecasted in 2009 by around £3 billion. In 2019, Professor Haskel’s methodology led to the inclusion of £6.2billion of previously unidentified investment in books, film and music in the National Accounts.

Figures show the volume of annual investments in “intellectual property products” has increased by a staggering 87 per cent in the European Union

The work has also been extended through the EU-funded SPINTAN project, which aims to build a public database of intangibles for a variety of EU and non-EU countries, and to analyse the impact of public sector intangibles on innovation, well-being and “smart” growth.

Using Professor Haskel’s work as a springboard, the ONS has also invested in developing experimental estimates of more intangibles than are currently in the National Accounts, leading to two publications of experimental statistics on intangibles in the UK.

"Jonathan’s work on intangibles over the past decade or more has been very valuable to the ONS, and I believe to the international community of economists and national statistical institutes," Jonathan Athow, Deputy National Statistician at the ONS.

"It is crucial that economic statistics continue to evolve to reflect the economy of the day, and the increasing importance of intangibles is a key aspect of this evolution. Jonathan’s work has helped to bring the importance and complexity of intangibles to the attention of the ONS and other NSIs [National Statistical Institutes], which has in itself has been extremely useful."