Written by

Published

Category

Key topics

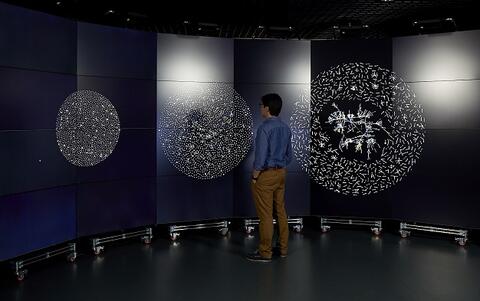

Data science studies the use of massive data sets analysed through new technologies, allowing us to uncover truths about society and businesses that were previously hidden. It enables us to implement automation, insights and intelligence at a scale previously unattainable

We are at the dawn of a new era of unruly change: data science and machine learning are reshaping business and society.

Data science is still evolving, but, in the last decade, it has come to be about building, exploring and exploiting modern data sets. Thanks to the internet and our mobile phones, modern data sets are treasure troves of potential insights about how people and things interact. Unsurprisingly, this knowledge brings both opportunities and worries.

To many, data-driven artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning technologies sound overwhelming; to others, it just sounds like sci-fi hype. There is a lot of talk about how data science, AI and machine learning will change organisations, careers and the world of work.

Facing changes many believe will prove historic, I have become interested in cutting through the hype to help businesses adopt and adapt to new capabilities. To that end, we are developing and using tools of data science and natural language processing (NLP) to examine job descriptions and organisation structures.

With this approach, we can build organisation-wide views of task-level interdependencies of work and organisation designs. Thanks to these new views of work and organisations, we are already seeing cool surprises – such as a far higher proportion of cognitive, communicative and relational work than we expected versus more embodied physical work that has historically been automated first.

As data science and AI supply technologies applicable to improving productivity on non-physical work, the next generation of technology-driven change to organisations and work is likely to bring substantial new changes. Just thinking about how so much work has been adapted to remote working during the pandemic, we already see how profound the changes will be. Making the most of these new technologies will take new thinking as systems start to affect not just lower paying jobs, but also better paying, higher skilled jobs that require significant training.

Applying data science in business

We are also exploring the human side of these changes: what are the individual, organisational, cultural and ethical implications of turning various aspects of work over to machines, and then collaborating with them?

Now is the time to consider how we want to accommodate and manage new layers of automation, insights and intelligence, without making the mistakes of the past. If we do this without conscious design and analysis, we’re going to replicate human processes with all the imperfections and weaknesses they entail. What wisdom around managing individuals and teams do we want to apply to managing systems and automation? If we don’t ask the people who are writing and implementing the algorithms to start thinking about this, then we’re in trouble.

As employers, educators, and policymakers grapple with these new developments, it’s common to hear talk about the skills gap in maths, science and engineering, but this isn’t quite what it seems: data science does demand new skills and training, to be sure, but equally, companies need to make use of the insights of their data scientists. All too often, even powerful insights do not have the impact people would want. Getting new tools and ideas into production systems is hard – that’s where you’ll find the bottlenecks.

Big data then, data science now

Before we called it “data science”, we saw so-called “big data” applications in digital marketing and the shift from bricks-and-mortar retail to e-commerce. These applications took off as people figured out how to use data gleaned from internet searches and surfing behaviour. Momentum built further as the internet made the leap to our mobile phones and social media platforms took their place alongside search engines as gateways to all kinds of content.

As the adtech world paved the way, we saw similar transformations in several other industries – for some time, you will have heard about fintech, proptech, cleantech, smart cities and so on. Data science is being used to catch and stop fraud, help you find your next flat or house, and even clean up the environment and make cities more liveable.

Data science is being used to rethink not only the work companies are doing, but also the boundaries of firms themselves and the architectures of industries. Already we are seeing profound changes in healthcare — just look at the way the vaccine is being rolled out in the UK. In a flash, the coordination and delivery of healthcare is being accelerated by the use of apps and mobile phones.

In changes that seem both weird and wonderful, people are also starting to talk to disembodied voices coming from the cloud – as in the data and computer somewhere at the end of the internet. This is thanks to a furious pace of development in NLP and understanding. Unlike the super-technical changes brought by adtech, fintech and so on, developments in NLP hold the promise of profoundly changing how we work with each other and machines.

Data science at Imperial College London

But we can’t trust AI-based systems if we don’t know about the data and model behind it. Is the data ethically sourced? Is it representative? Is the model validated for the conditions we face? Are systems replicating human behaviour that needs to be challenged and changed? Can we distinguish between unscrupulous modellers and those doing more thoughtful work?

And so, in a way, we are back to the challenges of Victorian times: struggling to build and humanise new technologies to keep the best of what they do, while eliminating deals and work practices that are deceptive and abusive.

One of the cool things about Imperial is that we invite our students to confront this turbulence, rather than keeping these fascinating problems to ourselves as academics. Even as we equip them with real-world skills, we also help them understand and grasp the possible. One of the best ways to do this is to offer opportunities to put newly acquired knowledge to work on real-world problems.

In the data science context, our Data Spark scheme does just that. Although we started with Business Analytics students, we are expanding to other business degrees and students across Imperial. Working in teams with an academic mentor and a client sponsor, students work on a particular issue and deliver their results directly to the organisation with the problem. To date, teams have completed projects in the not-for-profit sector, financial services, healthcare, energy, aerospace, and professional services such as consulting, law and accounting.

And rather than keeping these experiences to the select few who come to join us as students here in London, we’re working hard to reach a broader demographic. In our view, even prestigious universities have an obligation to serve the wider world. Our new Data Science Intensive course – in partnership with French company Le Wagon – is helping to cast the net wider still. That course is for early career changers with a level of maths and programming. They’ll learn the fundamentals of data science and how to code their own projects, and then have a chance to get their hands dirty with project work.

I love the idea of giving our students an extra experience that helps them succeed in the marketplace. We’re helping students grasp the possible and see the future. But that goes both ways. The best way to see the future is to understand what younger eyes are seeing.