Inside Imperial's Surgical Innovation Centre

A multidisciplinary centre at Imperial is pushing the boundaries of surgical innovation for the benefit of patients.

Anyone who has visited the fascinating Hunterian Museum in Bloomsbury will know the central role that John Hunter and colleagues played in the birth of modern surgery – pioneering medical procedures and advances at hospitals across London in the 18th Century.

Imperial has made its own contributions to that continuing story, for example in the 1950s at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School, where the world’s first heart-lung bypass machine was invented, built and then successfully used at Hammersmith Hospital.

Today Imperial’s academics and collaborators are booking themselves space in the Hunterian’s galleries of the future with advances that would astonish Hunter and his contemporaries. Within the Surgical Innovation Centre, spearheaded by Professor the Lord Darzi and formally opened by HRH The Prince of Wales last month, collaborative research, medical education and patient care flourish alongside each other as cutting-edge technology and multi-disciplinary teams combine to develop new surgical techniques.

Research

Dr Nisha Patel (Surgery and Cancer) is a gastroenterologist and Clinical Research Fellow at the Centre and is keen to emphasise the interdisciplinary nature of the innovation process and the diverse specialisms of the clinicians and engineers who make up the team.

Dr Nisha Patel (Surgery and Cancer) is a gastroenterologist and Clinical Research Fellow at the Centre and is keen to emphasise the interdisciplinary nature of the innovation process and the diverse specialisms of the clinicians and engineers who make up the team.

“I work together with surgeons from urology, orthopaedics and neurosurgery, as well as engineers focused on vision and imaging, kinematics and product design. We interact on a week-by-week basis and since we’re all housed in the same unit, we come up with projects and devices in a shorter period of time than we would otherwise achieve separately.”

The team has access to a number of 3D printers for making medical device prototypes, which they test out in an iterative process on the bench-top and with simulators.

Nisha is currently working with Imperial engineer Dr George Mylonas (Surgery & Cancer) on a robotic prototype device called CYCLOPS that attaches to a regular endoscope to facilitate the removal of colorectal polyps and early cancers. The unique aspect of CYCLOPS is the inclusion of an inflatable ‘anchor’ component that allows a greater level of manipulation and stability in tight spaces. Crucially this allows procedures to be performed through natural orifices, with no external incisions and therefore no scarring.

Lord Darzi and Prince Charles with Drs Nisha Patel and George Mylonas (L-R)

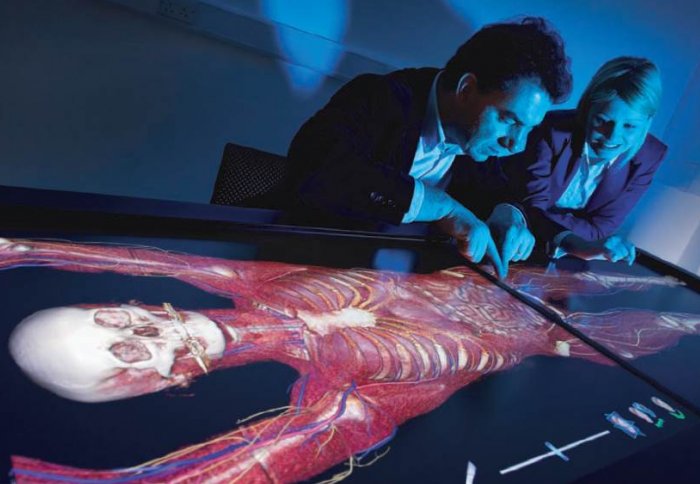

Advanced imaging methods are also playing an increasing important role in surgery. Nisha and team are currently building a surgical platform that displays endoscopic video feeds in 3D, with data from a patient’s CT or MRI scans overlaid in augmented reality fashion, for example showing the outline of the colon for use while performing rectal surgery.

“It’s like having sat nav for the body; you literally see where you are and where you are going which is really useful and improves your perception of how the tissues and surgeons are interacting,” says Nisha.

“I think convergence of technologies will play a big role in surgery in the future and do think there’ll come a time when I might be doing an endoscopy wearing something like Google Glass, with all the data and viewpoints displayed.”

Education

A key part of the Centre’s vision is in providing world class education and training to the next generation of surgeons – who will have more tools at their disposal than ever before.

The Centre has a suite of simulated clinical environments, including a ward, operating rooms and high-tech surgical theatre, allowing training and staff assessment across a range of professional disciplines.

Sarah Huf is a Clinical Research Fellow and Trainee in General Surgery at the Surgical Innovation Centre and lauds the benefit of this approach.

“Often at work you have to negotiate a busy ward with many interruptions, all whilst trying to keep focused on the task at hand. Replicating these distractions in the simulated ward can help us practice prioritisation and maintaining focus, as well as helping us to prepare for stressful situations we encounter for real,” she says.

The centre also contains a facility called ORCAMP, a simulation tool for training and assessment in a highly realistic operative environment, with hybrid operating room functionality. By simulating real equipment in combination with life-like medical scenarios, the goal is to rehearse realistic operation behaviour, both for the team and the individual operator.

The centre also contains a facility called ORCAMP, a simulation tool for training and assessment in a highly realistic operative environment, with hybrid operating room functionality. By simulating real equipment in combination with life-like medical scenarios, the goal is to rehearse realistic operation behaviour, both for the team and the individual operator.

One key advantage is that many of the simulation models are actually manufactured within the Centre and there is a close working relationship between the trainees and the model designers.

“Ultimately it’s about the opportunity to practise in a safe environment – whether you are a beginner practising basic skills in laparoscopic dexterity or fine tuning a specific surgical step,” says Sarah. “So when it comes to performing in the operating theatre you are prepared, which is better for us and more importantly safer for the patients.”

Patient-focused

The work of the Surgical Innovation Centre is a beacon within the Imperial College Academic Health Science Centre, a joint initiative of Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. This partnership aims to improve the quality of life of patients and populations by taking new discoveries and translating them into new therapies as quickly as possible. Over the past year, nearly 2,000 patients have been treated at the Surgical Innovation Centre, including those receiving pioneering gastrointestinal interventions, highlighted below.

case I - bariatric surgery in the surgical innovation c entre

Gastric bypass surgery, a treatment for morbid obesity, reduces the size of the stomach to that of an egg and connects it to the small intestine. This changes chemical messengers from the intestines to the brain so that the patients feel less hungry, eat less and regain a healthy weight. One patient who has benefited at the SIC is Allyson Frost, a mother of two. “This is the best thing I’ve ever done,” she said. “I finally have my life back. I had tried all of the diets available and while they worked for short periods of time the weight always crept back on. My doctor suggested that a gastric bypass was the best option for me. My operation went well and with the help of the staff, who really made me feel like an individual rather than a number, I was home within two days. Within five months I have hit my target weight, which I am so pleased about.”

case II - scarless cancer surgery at the surgical innovation centre

Julia Lonsdale, a nurse, had her bowel tumour removed through a small incision in the belly button using a technique called Single Incision Laparoscopic Surgery (SILS). Julia said: “I was sent a bowel cancer testing kit through the post by my local GP surgery just after my 60th birthday. I sent off my sample and was asked to attend for a colonoscopy. The colonoscopy revealed a very small, cancerous polyp. I was quickly offered the SILS operation which was marvellous. They removed all of the cancer through a tiny incision in my belly button. This meant that I didn’t have a huge open wound which takes a long time to heal and is susceptible to infection. I was able to go home after three nights with no scar, very little pain and a very short recovery time, which was brilliant.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Andrew Czyzewski

Communications Division