Why alcohol makes your brain feel good... and very bad

by Kate Wighton

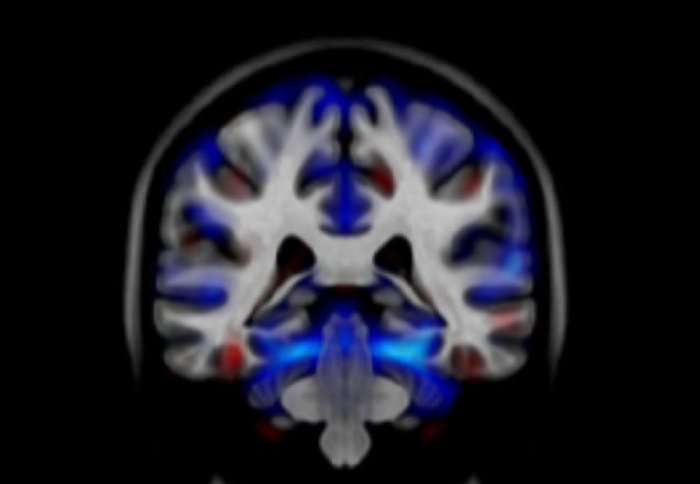

Brain scan of alcohol dependent person revealing areas (in blue) with less grey matter

Christmas festivities are now in full swing, with bleary heads aplenty. But what is the effect on our brains?

Scientists are only now beginning to unravel exactly why alcohol can prove so toxic to our brain cells.

“There has always been an assumption that alcohol rots your brain, but we need to know exactly how it does this,” explains Professor Anne Lingford-Hughes, chair in addiction biology from Imperial College London, who is at the forefront of research into alcohol’s effects on the brain.

The frontal lobe is exquisitely sensitive to alcohol - this is why people quickly become disinhibited.

– Professor Lingford-Hughes

Expert in addiction biology

“Not only are we increasingly realising that alcohol effectively shuts the whole brain down – and can even trigger inflammation within the brain - but we’re also seeing how long these effects last. This knowledge is crucial to understanding alcohol dependency, and giving people effective treatments.”

Here Professor Lingford-Hughes explains what happens to our brain when we have a drink.

Why that first sip tastes so good

That first swig of wine or beer rapidly causes changes in two types of brain chemicals. These orchestrate much of alcohol’s effects on our thoughts, feelings and coordination.

"One of these chemicals, called GABA, acts like a sedative to calm the brain down, while the other, called glutamate, excites the brain and makes it more active," says Professor Lingford-Hughes.

Alcohol quickly increases GABA function, which is why a drink relaxes us.

The reason karaoke is easier with a drink

One of the brain areas first affected by this imbalance in GABA and glutamate is the frontal lobe, explains Professor Lingford-Hughes, which is found just behind the forehead, and governs traits such as attention, planning and impulsivity.

"The frontal lobe is exquisitely sensitive to alcohol - this is why people quickly become disinhibited. As they drink more, their ability to think straight and integrate all of their thoughts become lost."

And then texting becomes trickier

One of the next areas of the brain to be affected is the cerebellum, which sits at the base of your brain at the back of the head, and is crucial to controlling movement.

"If you paralyse this through alcohol, your movements become uncoordinated, and your speech slurred. The muscles across your whole body become affected - even in your eyes. This is why your vision becomes blurred – although your eyes are still seeing fine in terms of vision, your eye muscles aren’t working properly so each eye isn’t looking in the same direction.”

Foggy memory and black outs

Those fuzzy memories from the night before are due to an imbalance in the part of the brain caused the hippocampus, which is vital for memory. “This area of the brain is sensitive to changes in glutamate, and so when levels start to swing out of control, it struggles to lay down new memories.”

In recovery

When we stop drinking, our brain struggles to re-adjust to the situation.

“Once alcohol is out of the blood stream, GABA function falls, but glutamate – which excites the brain - is still very high. This can lead to anxiety, shakiness and poor sleep. If you have been drinking very heavily, this sudden change can even lead to fits. Levels of another neurotransmitter in the brain – dopamine – are also affected which can lead to low mood.”

And high glutamate levels are bad news for our brain cells.

“Large amounts can prove toxic, as it seems to destroy all the delicate connections between brain cells - rather like pruning back a shrub until just a bare stump is left.”

As a result, explains Professor Lingford-Hughes, the after-effects from the festivities can last long into January.

“If someone has had a heavy Christmas they’ll feel pretty rough as the alcohol is going out of their system and their brains begin to readjust. We’re still unsure how long this takes but it could be a number of days, if not weeks. It will certainly take longer the older you are, as the brain takes longer to recover.”

Although Professor Lingford-Hughes is not suggesting everyone abstains from alcohol over the festive period – for the sake of your brain cells she urges sticking to sensible amounts.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Kate Wighton

Communications Division