Solar storms can be predicted a day in advance, shows mission to the Sun

Imperial kit aboard the Solar Orbiter mission to the Sun has been able to measure a solar eruption and predict its impact on Earth a day in advance.

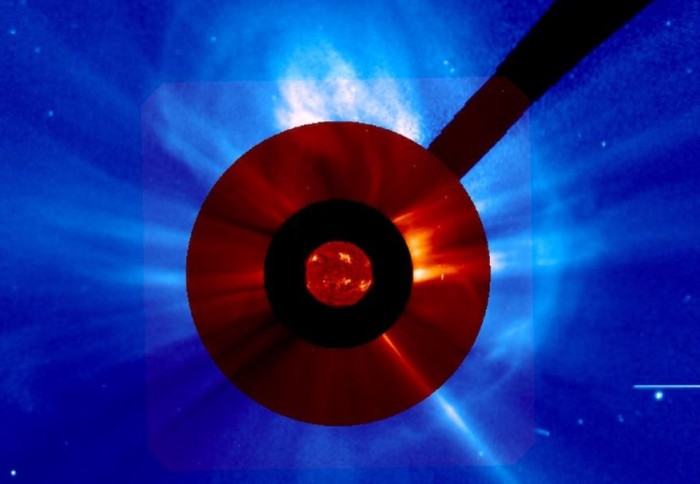

Solar storms occur when solar eruptions (or ‘coronal mass ejections’, CMEs) strike the Earth’s space environment. These powerful ejections of particles and magnetic field can interrupt satellites and power grids, affecting our way of life.

Several spacecraft orbit near the Earth that can detect these events, but because of their orbits, they can only give about 45 minutes’ notice of an incoming event. Solar Orbiter, while flying about halfway between the Earth and the Sun, was able to improve this forecasting power to give more than a day’s notice.

This was thanks to the spacecraft’s magnetometer, an instrument built and managed by researchers from the Department of Physics at Imperial that measures the magnetic field coming from the Sun. The team posted their predictions on social media, allowing aurora-hunters to get advanced notice of an opportunity to photograph some spectacular northern lights.

Predicting solar storms

Part of Solar Orbiter’s mission is to show how the solar wind changes as it moves out from the Sun towards Earth. Coronal mass ejections are a violent outburst from the solar wind, and the measurements of these taken by the magnetometer halfway between the two were remarkably similar to those taken many hours later by spacecraft nearer the Earth, showing these solar eruptions may not change much over this distance.

For the first time ever, the data from Solar Orbiter will allow us to work out what we could do with such a mission further from the Earth. Professor Tim Horbury

This is good news for extreme event prediction, since the measurements taken halfway between the Sun and Earth could be used to make accurate predictions of what will arrive at Earth. However, more events are needed to confirm this.

In order for a spacecraft to sit permanently in a position halfway between the Sun and Earth it would need to be propelled by a solar sail, which would require extremely light instruments. The results from Solar Orbiter show that investment in such technology development would be worthwhile.

Researchers at Imperial are also working on such light instruments, and have made a small version of the magnetometer for the RadCube technology-testing mission.

Principal Investigator for the magnetometer, Imperial’s Professor Tim Horbury, said: “For the first time ever, the data from Solar Orbiter will allow us to work out what we could do with such a mission further from the Earth, and demonstrate the kind of capability it could have.”

Real-time data

Solar Orbiter is having a complicated journey as it uses several ‘gravity assist’ manoeuvres around Venus and Earth to get closer to the Sun over the next couple of years. It is only while flying directly between the Sun and Earth for several months this year that this kind of prediction was possible.

This sustained alignment wasn’t planned, but once the team saw it was going to happen, they rapidly changed their procedures so they could analyse the data in near-real-time.

This required the work of MAG calibration engineer Virginia Angelini and MAG software engineer Edward Fauchon-Jones, who created algorithms to quickly clean the data (removing interference from the spacecraft itself) and send it to the team ready for analysis by the end of every ‘pass’ (eight-hour slot when the instrument collected data).

The data was then analysed by PhD student Ronan Laker in order to make predictions of the conditions of the solar wind once it reached Earth.

Professor Horbury said: “If you actually stop and try and write down all the steps that are happening with the processing in the background, it's extraordinary. If we'd said at the beginning when we were proposing the instrument and the mission, that this is what we would do, no one would believe us. The fact that it all hangs together is just amazing.”

The team are now prepared to take similar data the next time Solar Orbiter is aligned between the Sun and the Earth, and hope other instruments aboard the spacecraft will take inspiration and collect similar real-time data in order to fill in the picture of what happens when CMEs speed towards Earth.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division