Daniel Carrivick

(Geology 1998-2002)

Daniel shares his life risking tales of conquering mountain peaks and building bridges

Back in November 2000 a couple of friends at Imperial told me they were planning to go mountaineering in the Indian Himalaya the following summer and asked me if I wanted to join them. Never being one to miss an opportunity, I jumped at the chance. Little did I know then that it would be the first of many expeditions I’d undertake while at Imperial College.

We applied to Imperial College Exploration Committee for approval and funding. I remember going to meet the Committee to discuss our expedition plans. We went in full of confidence; convinced the Committee would support us. Some twenty minutes later we emerged from the grilling, having had our feet brought firmly back down to the ground. It was clear we were going to have to do a lot of rethinking if our dream of climbing in the Himalayas was to come true.

Our second meeting with the Exploration Committee went slightly better. We brought more experienced people to the team and scaled down our objectives. Even so there was a lot of work still left to do. The Committee gave us provisional approval, which made all the effort worthwhile. Six months later, we were on a plane to Delhi.

Having set up advanced base camp (ABC) there was only enough food and equipment for two people to make a summit bid. So I, and three other people, did our bit for the team and headed down to collect more supplies while the two remaining people made the first ascent of Tagne (6111 m). Our attention then turned to a neighbouring unclimbed peak. Halfway to the top I turned around, suffering from diarrhoea and concerned about the deteriorating weather coupled with the teams’ slow progress. That evening I waited anxiously in the tent for the others to return – they had continued on up towards the top and were long overdue. To my relief, they finally staggered in at 11pm, some twenty hours after setting out. They were hungry and exhausted but pleased to have made it to the summit of the 6030 m peak, which they later named Sagar, meaning ocean wave. I then attempted to climb Tagne with one other member of the expedition. Running out of time and faced with a difficult section, we turned round just yards from the top. The expedition was an amazing experience and although I didn’t reach any summits, I was pleased with how the team worked together to achieve its aims. Tragically, on the trek out, one of our horsemen was swept away while crossing a glacial melt water river, leaving us all a bit shaken.

Having set up advanced base camp (ABC) there was only enough food and equipment for two people to make a summit bid. So I, and three other people, did our bit for the team and headed down to collect more supplies while the two remaining people made the first ascent of Tagne (6111 m). Our attention then turned to a neighbouring unclimbed peak. Halfway to the top I turned around, suffering from diarrhoea and concerned about the deteriorating weather coupled with the teams’ slow progress. That evening I waited anxiously in the tent for the others to return – they had continued on up towards the top and were long overdue. To my relief, they finally staggered in at 11pm, some twenty hours after setting out. They were hungry and exhausted but pleased to have made it to the summit of the 6030 m peak, which they later named Sagar, meaning ocean wave. I then attempted to climb Tagne with one other member of the expedition. Running out of time and faced with a difficult section, we turned round just yards from the top. The expedition was an amazing experience and although I didn’t reach any summits, I was pleased with how the team worked together to achieve its aims. Tragically, on the trek out, one of our horsemen was swept away while crossing a glacial melt water river, leaving us all a bit shaken.

Photo above right: Camp with Sagar in the background.

The following year in summer 2002, I joined other friends at Imperial to explore unclimbed peaks in the Cordillera Apolobamba, Bolivian Andes. An ascent of a 5480 m unclimbed peak was made before the weather turned dumping lots of fresh snow. Then in a brief weather window we climbed Nevado Nubi (5710 m), wading endlessly through thigh deep snow to reach the top. I remember hurriedly getting down off the mountain, as a huge thunderstorm passed overhead, bombarding us with hail. With poor snow conditions we focused on the rocky peaks south of base camp. While scrambling, a falling rock broke our expedition leaders’ toe and we had to evacuate him on horseback. It took us five days to get him to hospital in La Paz by which time his foot had swelled beyond all recognition. With our leader heading home, we made an ascent of Illimani (6438 m), the highest peak in Bolivia.

The following year in summer 2002, I joined other friends at Imperial to explore unclimbed peaks in the Cordillera Apolobamba, Bolivian Andes. An ascent of a 5480 m unclimbed peak was made before the weather turned dumping lots of fresh snow. Then in a brief weather window we climbed Nevado Nubi (5710 m), wading endlessly through thigh deep snow to reach the top. I remember hurriedly getting down off the mountain, as a huge thunderstorm passed overhead, bombarding us with hail. With poor snow conditions we focused on the rocky peaks south of base camp. While scrambling, a falling rock broke our expedition leaders’ toe and we had to evacuate him on horseback. It took us five days to get him to hospital in La Paz by which time his foot had swelled beyond all recognition. With our leader heading home, we made an ascent of Illimani (6438 m), the highest peak in Bolivia.

Photo above: On the summit of Illimani in 2002.

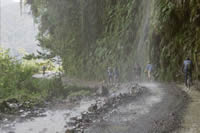

We then planned to climb in the Cordillera Real but road blockades set up by demonstrating bus and taxi drivers meant we couldn’t get out of La Paz. When the strikes ended there was not enough time to do any more climbing so we ended our expedition by rafting the Coroico River and cycling down the world’s most dangerous road – a 65 km single-lane dirt track which clung to the side of sheer drops, dropping over 3600 vertical metres from barren snow capped mountains down to lush rainforests.

We then planned to climb in the Cordillera Real but road blockades set up by demonstrating bus and taxi drivers meant we couldn’t get out of La Paz. When the strikes ended there was not enough time to do any more climbing so we ended our expedition by rafting the Coroico River and cycling down the world’s most dangerous road – a 65 km single-lane dirt track which clung to the side of sheer drops, dropping over 3600 vertical metres from barren snow capped mountains down to lush rainforests.

Photo above right: Cycling down the world's most dangerous road.

Soon after returning I got involved in a plan to traverse Greenland’s icecap with some other Imperial students. The Exploration Committee thought we were too ambitious so our plans were scaled back accordingly. Crossing the west coast pressure ridges is the hardest part of any ice cap traverse, so in July 2003 this was where we headed; our aim to find a route through the pressure ridges. Our fundraising got a boost when an overbooked outward bound flight saw us receive compensation in return for being put on the next flight. On top of this we were put up in a five-star hotel, with all expenses paid. This happened three times, so for five days we lived the high life in Copenhagen all while earning money to help pay for the expedition! On the ice we did not share the same luck. Construction on a 100 km long ice road which was usually built through the pressure ridges (to test cars) had only just begun. Thus we were forced to follow the remnants of the previous year’s road. Pressure ridges up to 15 feet high and crevasses some 10 feet wide meant we often had to go up to a kilometre out of our way just to cross these. And this had to be done three times for every ridge or crevasse because our supplies were too heavy to be hauled or carried all at once. One particularly bad day we made less than 5 km in 8 hours. There was a similar problem with melt-water streams, many of which were too wide to jump across. I remember one team member throwing their rucksack across one such stream, but it fell short and was carried downstream by the fast flowing waters. After a short chase the bag was luckily caught before the stream disappeared down a large sink hole in the ice. Eventually the pressure ridges got smaller and flatter ice was reached. We had a rest day before heading back the way we’d come and that afternoon there was a heart-stopping crack in the ice, followed by a thunderous roar. I looked outside the tent to see water gushing towards us through a stream channel which had become choked with ice. With water levels lapping at the foot of the tents we quickly threw everything into bags and moved them to the highest ice we could find. Thankfully the whole ice dam didn’t collapse and this restricted the initial amount of water released. Several long hours later the flood waters started to recede and we could make our way back to the tents. It took us just three days to get off the ice, crossing the same ground that had taken three weeks to cover on the way out, thanks to lighter loads and a newly built ice road. Rain fell almost continuously during this time and we were happy to get off the ice as quickly as possible.

Soon after returning I got involved in a plan to traverse Greenland’s icecap with some other Imperial students. The Exploration Committee thought we were too ambitious so our plans were scaled back accordingly. Crossing the west coast pressure ridges is the hardest part of any ice cap traverse, so in July 2003 this was where we headed; our aim to find a route through the pressure ridges. Our fundraising got a boost when an overbooked outward bound flight saw us receive compensation in return for being put on the next flight. On top of this we were put up in a five-star hotel, with all expenses paid. This happened three times, so for five days we lived the high life in Copenhagen all while earning money to help pay for the expedition! On the ice we did not share the same luck. Construction on a 100 km long ice road which was usually built through the pressure ridges (to test cars) had only just begun. Thus we were forced to follow the remnants of the previous year’s road. Pressure ridges up to 15 feet high and crevasses some 10 feet wide meant we often had to go up to a kilometre out of our way just to cross these. And this had to be done three times for every ridge or crevasse because our supplies were too heavy to be hauled or carried all at once. One particularly bad day we made less than 5 km in 8 hours. There was a similar problem with melt-water streams, many of which were too wide to jump across. I remember one team member throwing their rucksack across one such stream, but it fell short and was carried downstream by the fast flowing waters. After a short chase the bag was luckily caught before the stream disappeared down a large sink hole in the ice. Eventually the pressure ridges got smaller and flatter ice was reached. We had a rest day before heading back the way we’d come and that afternoon there was a heart-stopping crack in the ice, followed by a thunderous roar. I looked outside the tent to see water gushing towards us through a stream channel which had become choked with ice. With water levels lapping at the foot of the tents we quickly threw everything into bags and moved them to the highest ice we could find. Thankfully the whole ice dam didn’t collapse and this restricted the initial amount of water released. Several long hours later the flood waters started to recede and we could make our way back to the tents. It took us just three days to get off the ice, crossing the same ground that had taken three weeks to cover on the way out, thanks to lighter loads and a newly built ice road. Rain fell almost continuously during this time and we were happy to get off the ice as quickly as possible.

Photo above right: Ferrying equipment across pressure ridges in Greenland.

The hardships were soon forgotten though, and the following summer I was back in Greenland this time on the east coast ready to lead the same team across the ice cap. We hadn’t been able to get hold of any polar bear deterrents so we hastily made our way onto the ice and away from the east coast where the bears usually feed. After the first week the ice was relatively flat and our 80-100+ kg sledges acted like snowploughs in the soft snow. Nevertheless we were still able to average about 20 km a day. On day 21 we were forced to stop after just three hours when strengthening winds made it increasingly difficult to stand up. We battled to erect one tent and all four of us sought shelter inside. There we huddled for the rest of the day as unrelenting 80 mph winds threatened to rip our tent to shreds. Spindrift got in everywhere making it a long cold, damp night. Thankfully the winds dropped significantly the next morning and we were able to continue after digging everything out of the snow. Two days later disaster struck when my ski-binding broke. I was forced to continue on one ski which was much more tiring, but I was comforted by the fact we were only a few days away from reaching the ice road. We were disappointed to find the ice road had not been built. However, with sledges empty and melt-water streams still frozen our passage through the pressure ridges was relatively easy compared to the previous year. The crossing was completed in 29 days, giving us enough time for a stop-over in Iceland to see the sights on the way home.

The hardships were soon forgotten though, and the following summer I was back in Greenland this time on the east coast ready to lead the same team across the ice cap. We hadn’t been able to get hold of any polar bear deterrents so we hastily made our way onto the ice and away from the east coast where the bears usually feed. After the first week the ice was relatively flat and our 80-100+ kg sledges acted like snowploughs in the soft snow. Nevertheless we were still able to average about 20 km a day. On day 21 we were forced to stop after just three hours when strengthening winds made it increasingly difficult to stand up. We battled to erect one tent and all four of us sought shelter inside. There we huddled for the rest of the day as unrelenting 80 mph winds threatened to rip our tent to shreds. Spindrift got in everywhere making it a long cold, damp night. Thankfully the winds dropped significantly the next morning and we were able to continue after digging everything out of the snow. Two days later disaster struck when my ski-binding broke. I was forced to continue on one ski which was much more tiring, but I was comforted by the fact we were only a few days away from reaching the ice road. We were disappointed to find the ice road had not been built. However, with sledges empty and melt-water streams still frozen our passage through the pressure ridges was relatively easy compared to the previous year. The crossing was completed in 29 days, giving us enough time for a stop-over in Iceland to see the sights on the way home.

Photo above: The Greenland Traverse.

2005 saw me lead an Imperial expedition to Tibet, to explore a relatively unknown mountain range. We flew to Kathmandu and made our way north through the Himalayas. Our first night in tents was interrupted when thunderstorms caused the brook we were camped by to swell out of all proportion, bursting its bank and flooding the plain. I awoke to anxious shouts shortly before midnight to discover water beneath my tent. Unable to find my torch I ran my hands through the murky waters in the porch to try to find my shoes but they were long gone. The fast flowing water threatened to wash the tent away so I sat there holding it down while other people got out and held onto the tent. Still in our underwear, we dragged the now collapsed tent through the gushing water to dry land before wading around barefoot in the freezing water salvaging whatever we could. Thanks to some swift action and quick thinking from our base camp staff, our losses were minimised and even my shoes were returned to me the next day. The poor weather continued and low clouds meant we barely saw the mountains we were there to climb for the first two weeks after setting up base camp. The weather improved briefly for two of my team to get up high but then heavy snow came in trapping them there. Forced to move on by a shortage of food, they braved deep snow and white-out conditions to reach the top a 6603 m (21,663 ft) peak later named Jemakari Thobo (Sugar High Mountain), before returning to base camp.

2005 saw me lead an Imperial expedition to Tibet, to explore a relatively unknown mountain range. We flew to Kathmandu and made our way north through the Himalayas. Our first night in tents was interrupted when thunderstorms caused the brook we were camped by to swell out of all proportion, bursting its bank and flooding the plain. I awoke to anxious shouts shortly before midnight to discover water beneath my tent. Unable to find my torch I ran my hands through the murky waters in the porch to try to find my shoes but they were long gone. The fast flowing water threatened to wash the tent away so I sat there holding it down while other people got out and held onto the tent. Still in our underwear, we dragged the now collapsed tent through the gushing water to dry land before wading around barefoot in the freezing water salvaging whatever we could. Thanks to some swift action and quick thinking from our base camp staff, our losses were minimised and even my shoes were returned to me the next day. The poor weather continued and low clouds meant we barely saw the mountains we were there to climb for the first two weeks after setting up base camp. The weather improved briefly for two of my team to get up high but then heavy snow came in trapping them there. Forced to move on by a shortage of food, they braved deep snow and white-out conditions to reach the top a 6603 m (21,663 ft) peak later named Jemakari Thobo (Sugar High Mountain), before returning to base camp.

A week later the weather improved substantially and I climbed with one other person to reach the top of two previously unclimbed peaks, one 6210 m (20,374 ft) high and the other 6390 m (20,964 ft). These we named Tsachenbori (Precious Mountain) and Sum Kangri (Three Snowy Mountains) respectively. Out of food we packed up base camp and drove to Lhasa, spending a few days there to see the sights before returning to Kathmandu along the Friendship Highway. Photo right: On the ridge climbing up Mount Tsachenbori.

A week later the weather improved substantially and I climbed with one other person to reach the top of two previously unclimbed peaks, one 6210 m (20,374 ft) high and the other 6390 m (20,964 ft). These we named Tsachenbori (Precious Mountain) and Sum Kangri (Three Snowy Mountains) respectively. Out of food we packed up base camp and drove to Lhasa, spending a few days there to see the sights before returning to Kathmandu along the Friendship Highway. Photo right: On the ridge climbing up Mount Tsachenbori.

A few months after getting back someone got in touch with me about a project to build a footbridge in a remote part of Malawi. Having been unable to find anyone to do the project, I decided to take it on myself with some other Imperial students. We travelled out last year, in July 2006, to have a look at the site and if suitable, build the bridge. The expedition did not get off to a good start when our luggage failed to arrive with us in Lilongwe (the capital). Then while driving north our progress was halted when a man ran out in front of the expeditions’ three tonne truck. We assisted where we could but sadly the casualty died that night in hospital from his injuries. The police were informed and formalities dealt with before we continued somewhat subdued. Once on site it soon became apparent the bridge span was going to be a lot greater than anticipated, which forced major design changes and logistical complications. Some 45 local inhabitants were employed to help construct the bridge and collect sand, gravel and rocks from the river. Meanwhile our truck was almost continuously on the go, bringing eleven truck loads of timber, bricks and cement, some of which involved a three day round trip to Mzuzu - the nearest industrial town. The scariest moment on site was when a 2.5 m long hissing snake flew into one of the 3 m deep anchor pits where concrete was being laid. Fortunately everyone clambered out of the pit just in time and no one was harmed. We worked dawn till dusk, seven days a week, to finish the towers and anchors on time. However, a delay in the delivery of the cables, which had been donated from Italy, meant we had to leave before completing the bridge.

A few months after getting back someone got in touch with me about a project to build a footbridge in a remote part of Malawi. Having been unable to find anyone to do the project, I decided to take it on myself with some other Imperial students. We travelled out last year, in July 2006, to have a look at the site and if suitable, build the bridge. The expedition did not get off to a good start when our luggage failed to arrive with us in Lilongwe (the capital). Then while driving north our progress was halted when a man ran out in front of the expeditions’ three tonne truck. We assisted where we could but sadly the casualty died that night in hospital from his injuries. The police were informed and formalities dealt with before we continued somewhat subdued. Once on site it soon became apparent the bridge span was going to be a lot greater than anticipated, which forced major design changes and logistical complications. Some 45 local inhabitants were employed to help construct the bridge and collect sand, gravel and rocks from the river. Meanwhile our truck was almost continuously on the go, bringing eleven truck loads of timber, bricks and cement, some of which involved a three day round trip to Mzuzu - the nearest industrial town. The scariest moment on site was when a 2.5 m long hissing snake flew into one of the 3 m deep anchor pits where concrete was being laid. Fortunately everyone clambered out of the pit just in time and no one was harmed. We worked dawn till dusk, seven days a week, to finish the towers and anchors on time. However, a delay in the delivery of the cables, which had been donated from Italy, meant we had to leave before completing the bridge.

Photo above: Mixing the concrete in front of the towers.

So this summer, July 2007, we returned to Malawi to finish the bridge. Our cables were still at the airport waiting to be cleared by customs. After several days, many meetings and lots of form filling we managed to get the import duty waived and the cables released. We headed north, apprehensive about what the annual floods might have done to the river banks and the superstructure. Everyone was relieved to find the site in a similar state to how it was left, just a lot more overgrown. Before the site had been fully cleared I was struck down with a fever and spent most of the next few days flat on my back. With no improvement in my condition I went to see a doctor in the nearest town, some twelve hours drive away. He diagnosed malaria and I was put on a course of strong drugs. However, subsequent tests done back home suggest I never contracted Malaria ?!? Nevertheless after a weeks course of drugs I was back up on my feet helping around the site. Some thirty workers helped carry the cables to the site and haul them into place. We then used high rope access equipment to attach linking cables and lay the wooden deck walkway. Meanwhile work was also undertaken to protect the riverbanks in front of the towers and to build an embankment on the approach to each sides of the bridge. The completion of the bridge was marked by a day of celebrations involving the whole community, during which the village chief and National Park manager jointly opened the bridge. When the locals stepped onto the bridge for the first time they were a bit apprehensive because the sway was nothing like any of them had ever experienced before. However, their smiles grew with every step and by the time they reached the other side they were bounding with joy. It was all quite emotional, especially when we saw just how much the bridge meant to them. Photo above right: The finished bridge in Malawi 2007.

So this summer, July 2007, we returned to Malawi to finish the bridge. Our cables were still at the airport waiting to be cleared by customs. After several days, many meetings and lots of form filling we managed to get the import duty waived and the cables released. We headed north, apprehensive about what the annual floods might have done to the river banks and the superstructure. Everyone was relieved to find the site in a similar state to how it was left, just a lot more overgrown. Before the site had been fully cleared I was struck down with a fever and spent most of the next few days flat on my back. With no improvement in my condition I went to see a doctor in the nearest town, some twelve hours drive away. He diagnosed malaria and I was put on a course of strong drugs. However, subsequent tests done back home suggest I never contracted Malaria ?!? Nevertheless after a weeks course of drugs I was back up on my feet helping around the site. Some thirty workers helped carry the cables to the site and haul them into place. We then used high rope access equipment to attach linking cables and lay the wooden deck walkway. Meanwhile work was also undertaken to protect the riverbanks in front of the towers and to build an embankment on the approach to each sides of the bridge. The completion of the bridge was marked by a day of celebrations involving the whole community, during which the village chief and National Park manager jointly opened the bridge. When the locals stepped onto the bridge for the first time they were a bit apprehensive because the sway was nothing like any of them had ever experienced before. However, their smiles grew with every step and by the time they reached the other side they were bounding with joy. It was all quite emotional, especially when we saw just how much the bridge meant to them. Photo above right: The finished bridge in Malawi 2007.

Looking back now over the past seven years I realise how lucky I have been to have these amazing opportunities. Each expedition has had its ups and downs and been a lot of hard work, but this has only increased my learning and sense of accomplishment. I would therefore like to thank Imperial College, London for having procedures and a recognised body in place to enable its students to fulfil their expedition ambitions and dreams. And I’d like to thank that body, Imperial College Exploration Committee for their guidance, backing, dedication, and financial assistance over the past seven years.

© 2007 Imperial College London

Through the first decade of the twenty-first century the campaign seeks to philanthropically raise £207 million from Imperial’s alumni, staff and friends, and donations from charitable foundations and industry.

Where your support can make a differenceGive now

Imperial’s Centenary Year provides an opportunity to recognise and celebrate members of the Imperial community.

View staff and student portraits