Going behind the scenes on the restoration of Imperial's iconic centrepiece...

You may have noticed Imperial’s iconic Queen’s Tower has been wrapped in scaffolding for the last few months. The reason for this is that the 138 year old tower is undergoing some much needed maintenance to its stonework and copper roof. Below, we dive into the project to learn more.

What is the Queen’s Tower?

The Queen’s tower is the only remaining part of the Imperial Institute building, opened by Queen Victoria in 1893. The Institute was not a success, and the buildings were partially taken over by the University of London in 1899. In 1956 it was proposed to demolish the Imperial Institute, as the Victorian buildings were not considered suitable for the expansion of Imperial College London. A campaign to preserve the building, led by then Poet Laureate, John Betjeman, led to a compromise where the Queen’s Tower would be left standing while the surrounding Institute buildings would be demolished.

The Imperial Institute in 1957, shortly before the demolition of the building, apart from the Queen’s Tower.

Serious scaffolding

Erecting the scaffolding to allow access to the top of the tower was no mean feat as it is nearly 90 metres tall (287ft). Some of the brickwork is also in a fragile state, and the tower is a listed building, so the scaffolding had to be put up without touching the tower itself. In addition, the stonework at the base of the tower had to be protected. All this had to be done while minimising disruption, and ensuring the safety of staff and students.

The scaffolding was started in October 2022 and took several months to construct. It uses 300,000 feet of tube and around 92,000 fittings. The technical difficulty of the build led to the project being featured in ScaffMag, the trade magazine for scaffolders.

The complex scaffolding surrounding the Queen’s Tower.

Copper top

One of the main focusses of the restoration work is the copper dome at the top of the tower. Copper roofs are tougher than standard roofs, and don't suffer the issues of standard roofing, but after well over a century even a copper roof needs to be replaced.

The good news is that copper is easily recyclable, so all the copper for the new roof is recycled from existing materials. The copper for the Queen’s Tower is coming from Finland, from a German-owned company which - at 150 years old - is a similar vintage to the tower. The copper was bought at the beginning of the project, to guard against price increases, and is being kept in a bonded warehouse for security.

Working with copper is a highly skilled job and there are few people with the required skills in the UK. Fortunately the cinematically named Full Metal Jacket have been contracted to carry out the work on the dome.

Most of the copper roofs we see today are old and have a characteristic green colour caused by the copper reacting with chemicals dissolved in rain. As it is newly recycled, the copper on the dome will have a shiny appearance, but over time will take on the familiar green ‘patina’ colour. The finial at the very top of the tower will also be repaired and regilded in gold leaf, so it should all look pretty dazzling when unveiled.

Brand new copper for the dome at the top of the tower. It's shiny glow will turn green over time. Marks and dirt are as a result of surrounding ongoing building work; the copper will be recleaned before unveiling. Photos Dan Weill Photography.

Delicate stonework

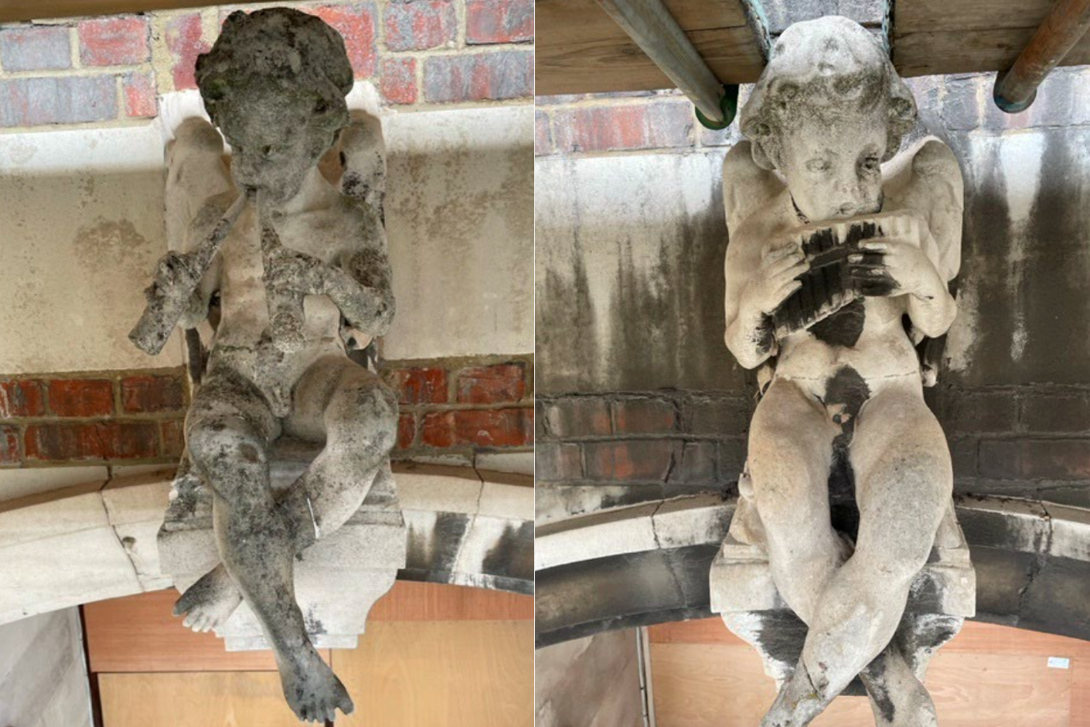

The brickwork and York stone are also in need of attention, particularly on the south and west side of the tower which face the strongest and most damaging winds. The effects of erosion are very noticeable on the four putti (sculptures of winged children) that adorn the top of the tower.

Two putti in situ pre-work, showing signs of corrosion and discolouration.

To restore the putti to their former glory, an expert mason will first clean them with a specialised system using water and compressed air. Any missing sections of stone will have new stone inserted, held in place by stainless steel dowels. The stone will then be recarved to fit in with the existing stonework. Finally, a ‘shelter coat’ made of putty and stone dust will be applied to provide protection from the elements.

Any bricks that are badly eroded are also being replaced – some were so corroded that the front crumbled off when touched.

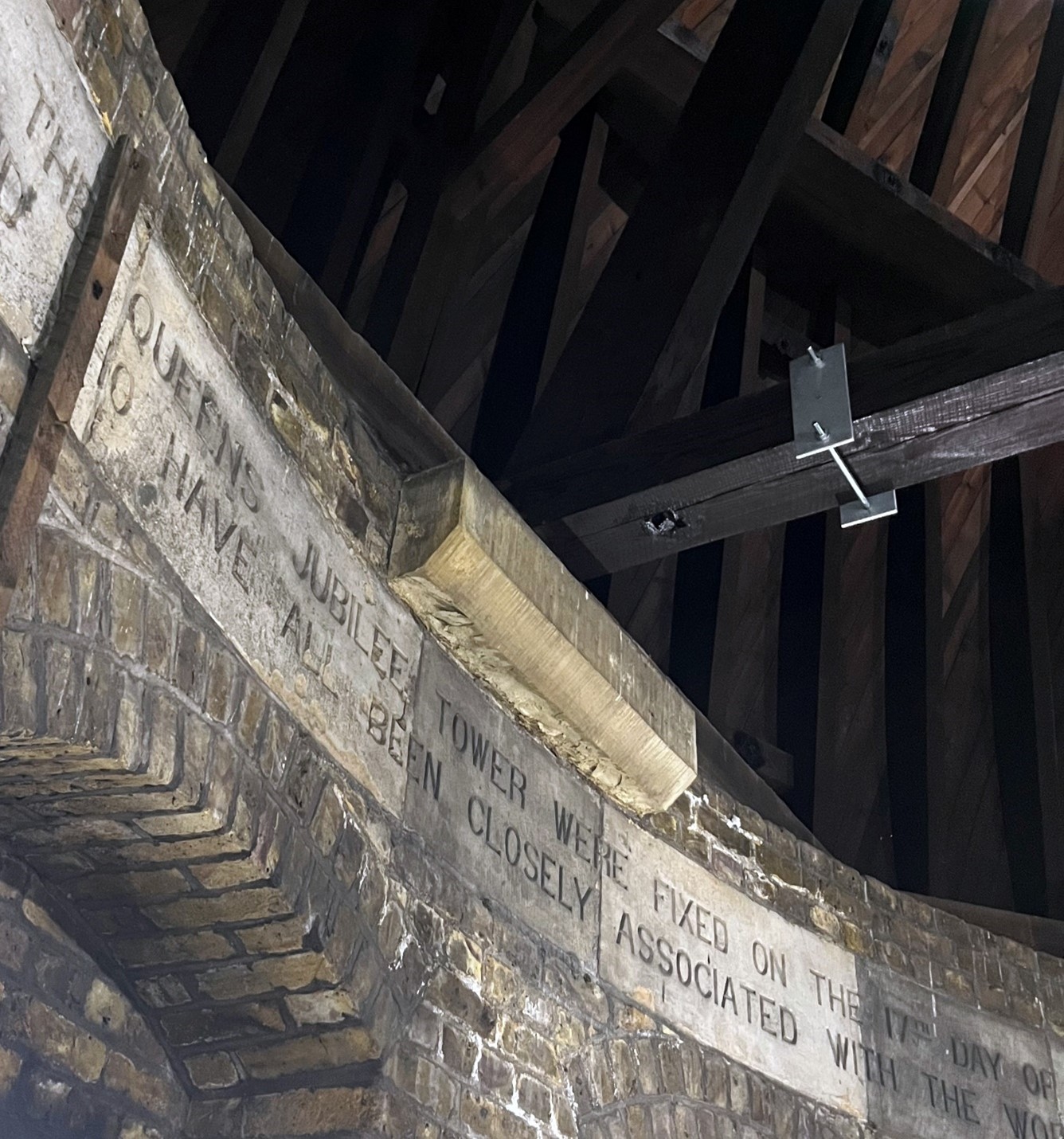

Inscriptions on the inside of the tower's roof.

Royal bells

There are ten bells located halfway up the tower. As part of the renovation work, the wooden louvres from which the sound of the bells emanates are being restored. The bells, however, are still in working order and are rung on royal anniversaries by a group of campanologists, some of whom are alumni or current staff.

Each of the bells in the tower is named after a member of Queen Victoria’s family - the largest is named the Queen Victoria, and the smaller bells are named after her three sons, her daughter-in-law Alexandra, and Edward VII’s five children.

During the restoration work the bells have remained silent except for being rung muffled, in commemoration of the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, and in celebration of the Coronation of His Majesty King Charles III and Queen Camilla in 2023.

The bells were rung again on 25 January 2025 in memory of The Revd Brooke Kingsmill-Lunn, for many years the Ringing Master at the Queen’s Tower.

Ringing the bells in the Queen’s Tower.

Ready for the next 150 years

The restoration work is expected to be completed by January 2026, with the scaffolding being dismantled from June this year. The Queen’s Tower is arguably Imperial’s most recognisable building - this restoration project should ensure the tower is well placed to weather another 150 years at the centre of Imperial’s South Kensington campus.

Timeline

- July to April 2025: Stone cleaning

- July 2024 to August 2025: Replace copper dome

- September 2025 to January 2026: Dismantle scaffolding

- February to April 2026: Repair stone steps around the base of the Tower