If Jim Platt’s (Mining Geology 1960) life were a book, the title would be ‘Sliding Door Moments’.

Over decades of learning, travelling and making life-long friends, being blown off course has always brought Jim more comfort than discouragement.

From the seemingly inconsequential decisions that led him to Imperial, to the series of events that landed him his first jobs across Africa and beyond, to the disaster of catching malaria – only to meet his future wife on a plane he wasn’t supposed to be on - it is perhaps hard to argue that fate had nothing to do with the way things turned out.

Now settled and retired in the Netherlands, Jim’s family has grown since he made the move in 1979. Today he is authoring books amongst other personal projects, including working as assistant to granddaughter Lilly, who has been tackling plastic pollution since she was seven under her initiative, Lilly’s Plastic Pickup.

For Jim, “being an Imperial alumnus is like fine wine that gets better and better with time and is evermore an element of life that one wouldn’t be without.”

We are grateful for the chance to share his story.

Why did you choose to study at Imperial?

I feel it was a choice made for me, rather than one I made myself! I grew up in an isolated coastal community in Cornwall, one of a lucky post-war generation to which opportunity to progress in education was opened.

I was able to attend grammar school (Sir James Smith’s at Camelford in Cornwall), a privilege essentially denied to many in my mother’s generation.

The pivotal event that led me to Imperial was a sliding doors moment, when in the fourth form at school I was given the choice to proceed to O-Level in either Latin or physics.

I very much liked our Latin teacher, and the opposite was true of the physics teacher, and so I chose Latin. I have never had cause to regret it. My A-Level subjects were then chemistry, maths and geography, a diversion from the school’s norm of chemistry, maths and physics. With some advice, my course was set on the path of geology.

I had interviews at both the University of Birmingham and Imperial, and was offered a place at both, but I had fallen for Imperial and the Royal School of Mines (RSM) at first sight - fate smiled on me there and then.

Can you tell us about your studies at Imperial?

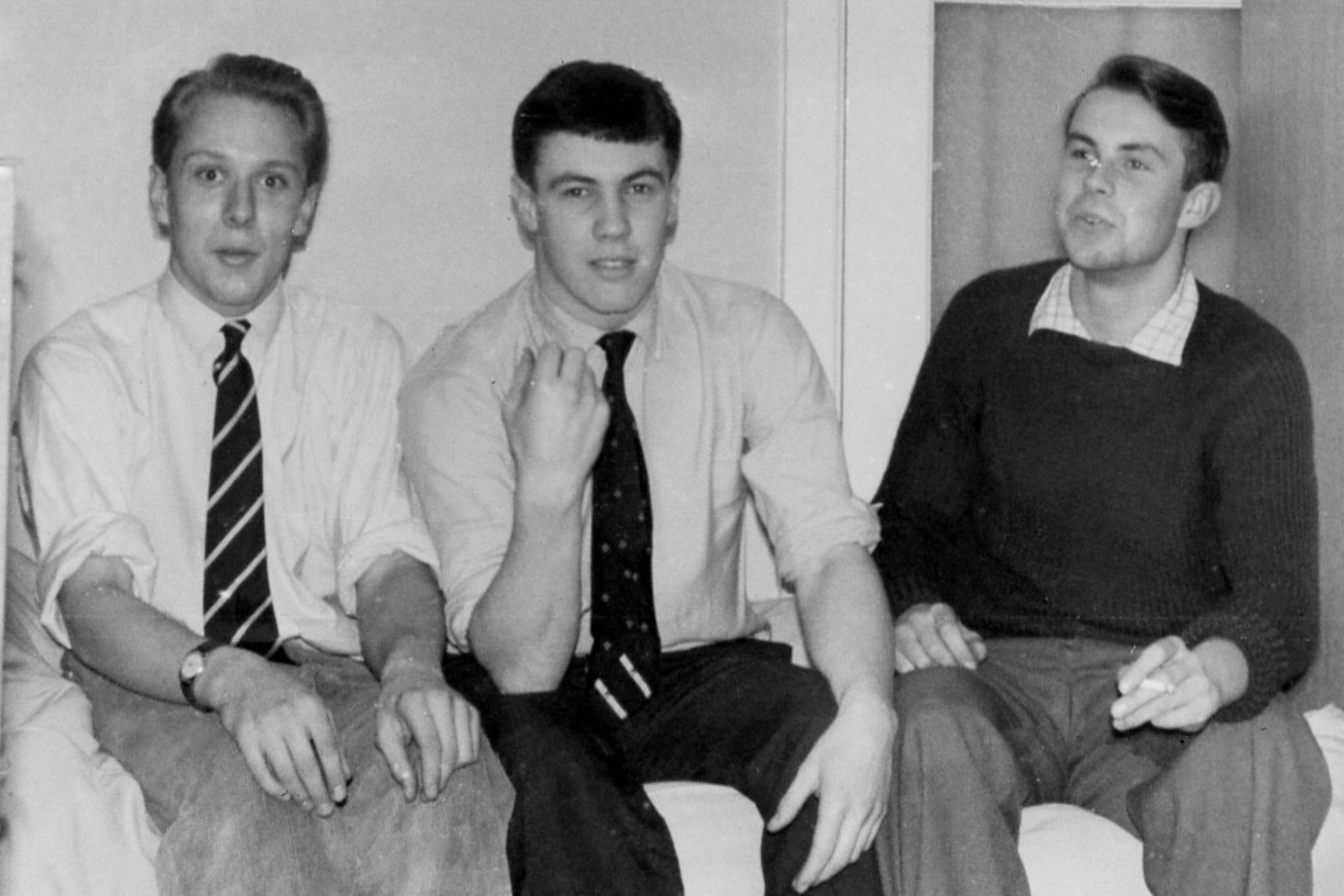

During first year, I lived in student ‘digs’ in Fulham, applied myself to studying and did well.

In second year, I had a shared room with two others in Prince's Gardens (known as ‘Garden Hostel’ at the time) and went right off the rails, as if the social genie had been let out of the bottle. It was a formative time.

By third year, I resided in room 77 on the seventh floor of the then brand new Weeks Hall residence in Prince's Gardens and got my act in order again.

I never saw myself as a scientist in the pure sense, but I was always comfortable with practical applications, field work and boots on the ground.

I joined the Imperial College Boat Club during freshers under the illusion that my experience of rowing punts around the harbour in Port Isaac in Cornwall where I was born and grew up, was relevant to rowing in eight on the Thames. With some adjustment, I rowed for the three seasons of my time at the RSM.

My other sporting association was in boxing. Perhaps because of my boxing association, I was elected ‘keeper and guardian’ of the RSM mascot, Mitch, a Michelin man painted in the RSM black, white, and gold colours, appropriately named in honour of the then Dean of RSM, Professor JC Mitcheson. A phalanx of us once ran Mitch from the RSM building through the adjoining City and Guilds building and out into Exhibition Road. The opposition was fierce, and all involved were fined.

What did you learn during your time here, in class or out?

My learning was more of the out of class category than in class. My teachers - professors, readers, lecturers, and technicians alike - were people of expertise and character, never short on giving and assisting. They are all remembered with gratitude and pleasure for what they did for me. It is a major regret in my life that I can’t go back and thank them for it.

As mentioned, I had come up to London from an isolated rural community on the north coast of Cornwall. Life there was in thrall to the war, and even when the conflict was over, we lived in its shadow.

Every day it seemed like I was being told by someone who had served in the Second World War that they hadn’t fought and sacrificed to allow me to do, well, pretty much anything was fair game.

It was strange that we never got that from Great War veterans. At any rate, what it gave many of us was a guilt complex, and an antipathy to foreigners, specifically those against whom my fellow villagers had “fought and sacrificed”.

I had to unlearn all of this prejudice. Exposure to the wonderful city of London and its people, and with the focus on Imperial and the diversity of the student population around me, did just that. I love the diversity of the world. Imperial led me along that good road - the road not taken.

Who did you find inspiring at Imperial and why?

Here is a list of people and their various roles at the time:

- Professor David Williams, who was Dean of the RSM

- Dr A P Millman, Reader in Mining Geology

- Dr Tommy Thomas and Mr Ben Parker of the Mine Surveying department

- Mr Brian Wallace, Hon Sec of the RSM Union

- Mr Roger Fisher, captain of the RSM Rowing Club

- Mr Richard Garnett, President of the ICU

- Mr Pete Grimley, mining Geology PHD student

- Mr Doug Owen, mining student

To a person they were each kind and considerate, always ready to guide and listen, and made me feel valued, and an element of something that was greater than the sum of its parts.

What is your fondest memory of your time here?

All my memories of Imperial are fond ones. I met so many good people with whom I am friends to this day, and that has blessed me along the way.

As well as the top quality grounding in science and technology that I was so fortunate to receive at Imperial, I learned to have confidence in myself, that it wasn’t who you were, but what you were that counted.

Imperial showed me that I had no reason to feel any sense of inferiority. I could be myself and be accepted. I am ever grateful to my peer group for that.

What is your favourite place at Imperial and why?

The Union Bar! Where else?! The greatest level playing field ever. In the Union Bar, we are all one fellowship and time has stood still to make us all students again!

How did your career begin?

As has been said above, the kind hand of fate brought me to the RSM, a constituent College of Imperial, to undertake Mining Geology. It was in this combination of disciplines that I found my feet.

There is nothing random about a mine - each one is a distinct and living entity exploiting and optimizing a body of mineralization that can hopefully be extracted at a profit. I found, almost unexpectedly, that I could embrace mines and grasp their elements. On a mine, as well as in mineral exploration projects, the geologist is perhaps the one member of the team that goes everywhere, knows everyone, and sees everything.

Between my second and third years, my summer project was to map and assess the geology of two small underground barite mines in southwest Scotland, one in Renfrewshire, and one in Ayrshire. The first great thing to benefit me was the comradeship of the miners. The second was to be drawn into local culture, which gave me a love of Robert Burns and his works that has never left me.

At the end of my third year, I was interviewed for a position as a field geologist on a nation-wide diamond exploration campaign in East Africa in the then Tanganyika (present day Tanzania).

I was asked about my Scottish mining experience by the interviewer, who was the Head of Personnel of the company involved, and the name of Robert Burns inevitably came up. It turned out that my interviewer was a serious fan of Burns, and we talked about the The Bard for the entire interview, at the end of which I was offered the job without hesitation. Burns got me my first job! You can never discount the thread of fate playing a hand.

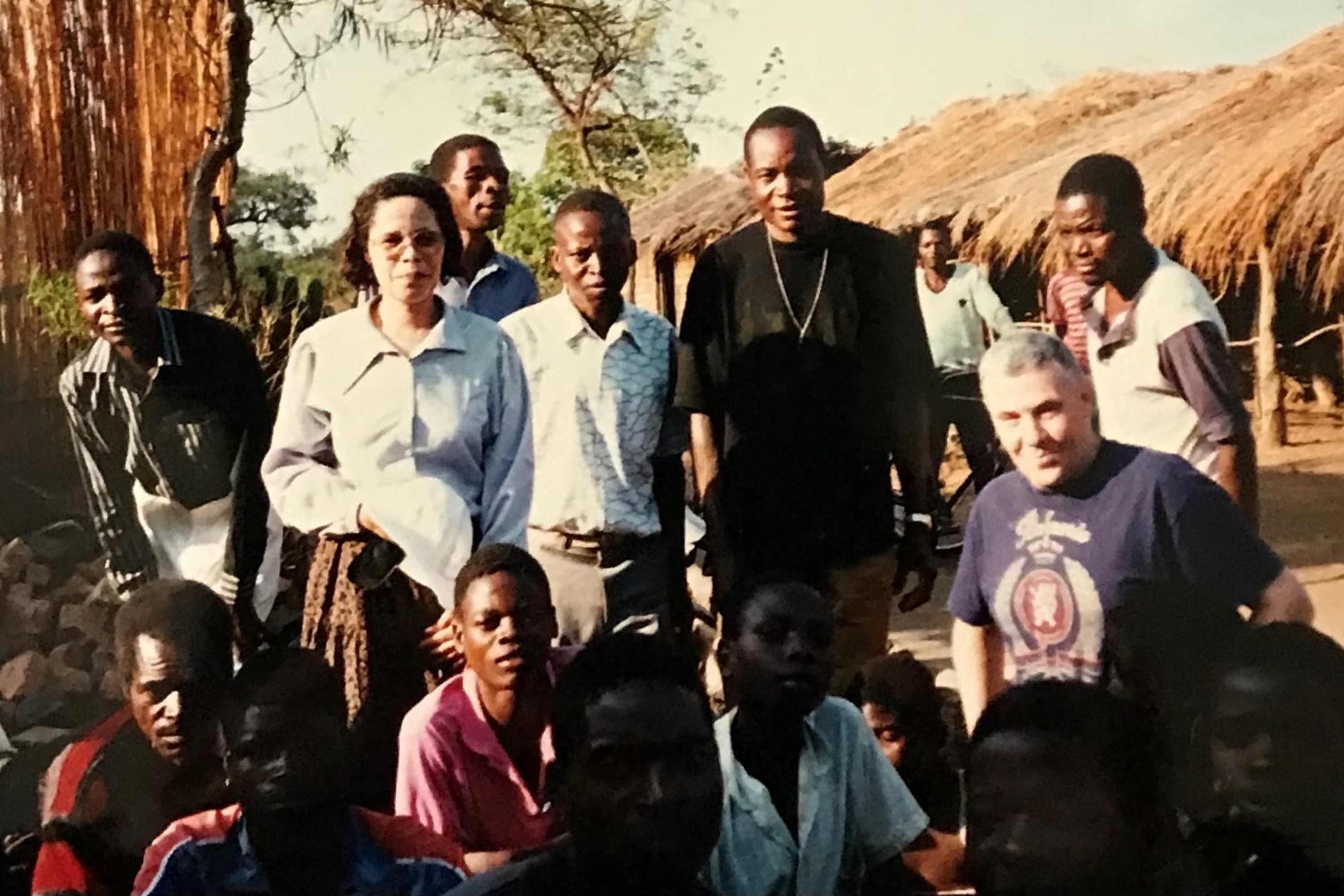

Following graduation I worked in diamond exploration based on bush camps in Tanganyika, the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana), Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Nyasaland (now Malawi) for four years.

I didn’t learn too much geology in the process, but I learned such a lot about Africa, its peoples and their aspirations, its wildlife and natural history, plus the battle against injustice. I was later transferred down to Botswana from Tanzania, when very heavy rains in the latter made working in the bush impracticable. Botswana suited me down to the ground - like living a dream! I worked around the fringes of the Kalahari Desert, where we found the first diamond in a stream gravel sample, which led to the later discovery of the Orapa diamond mine.

What happened next?

By then I was working along the now Zambian-Malawi and Malawi-Mozambique borders, still on the hunt for Diamonds.

Due to political unrest in Malawi, we went to Salisbury (now Harare, Zimbabwe), for Christmas in 1963. Unfortuntately I had contracted malaria in Malawi and had a particularly bad attack in Salisbury which put me out of action. As it happens, I had to return to Malawi a week later than scheduled…

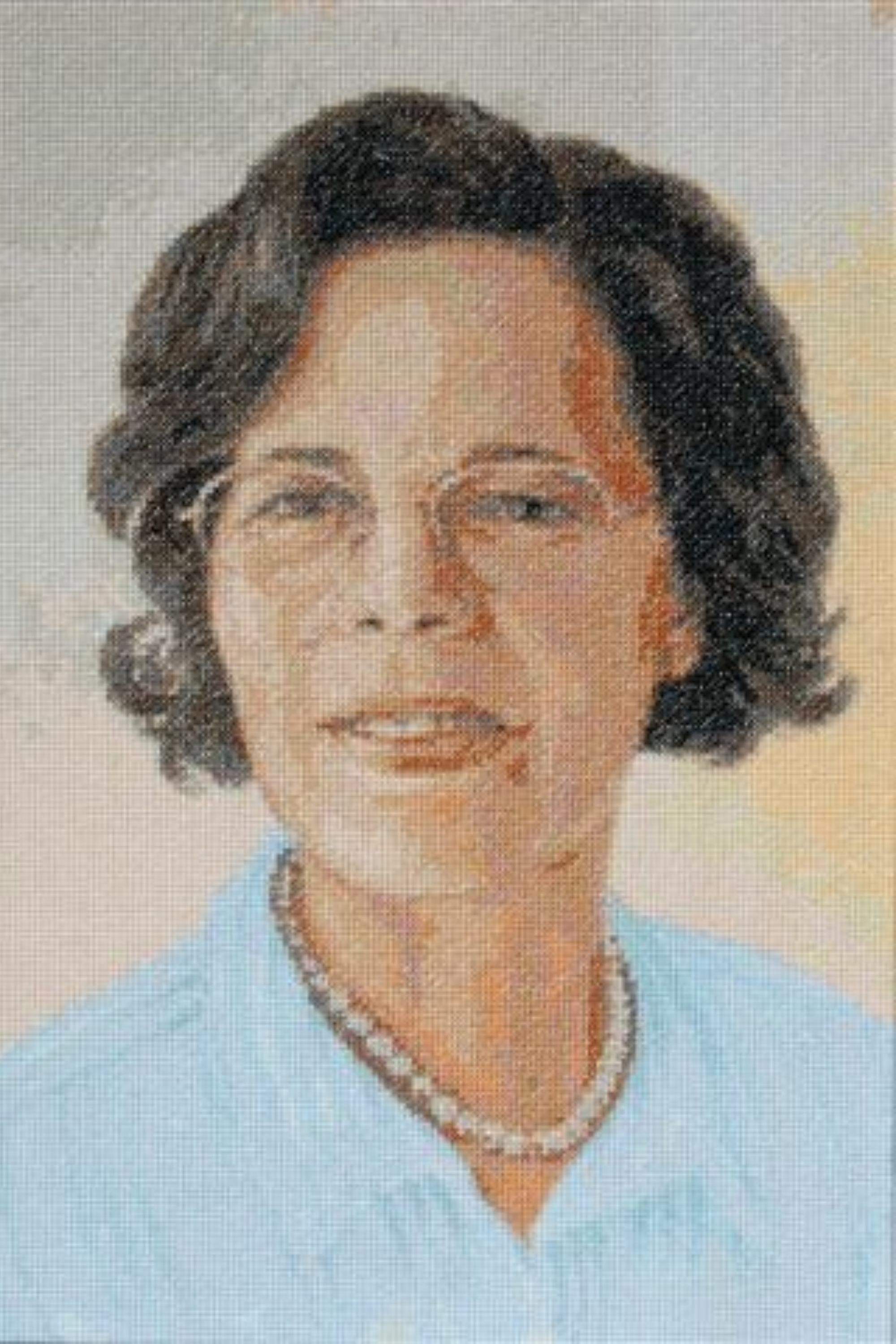

I flew back to Blantyre from Salisbury, and was seated beside a girl, Maria.

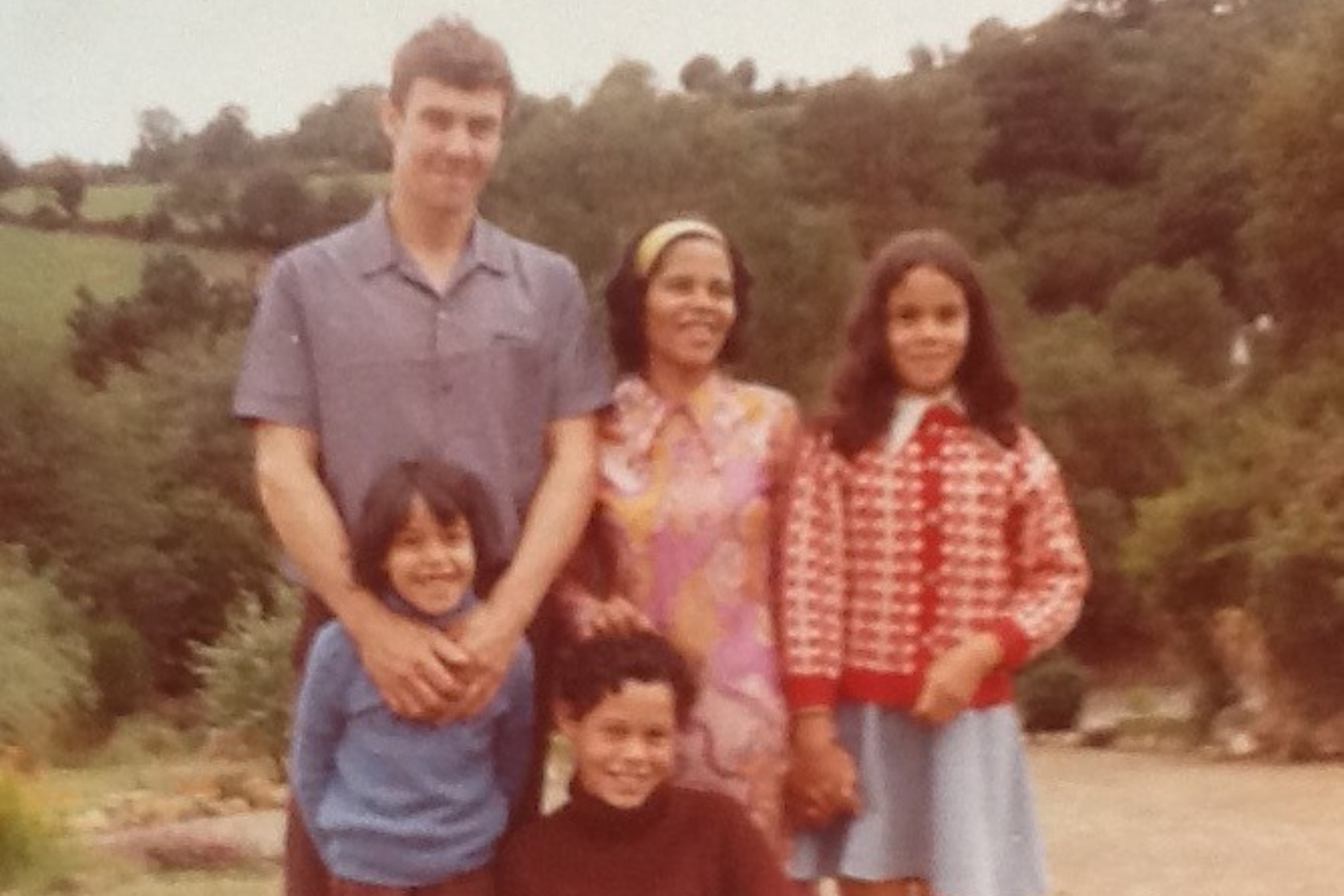

Maria and I married in Salisbury some nine months later. You could argue that this malaria attack was my greatest ever sliding doors moment.

And then there were two

Maria was of Italian and African parentage. The Apartheid was endemic in South Africa at the time, and as I worked for a South African Company, I was required to resign my position, which I did, and thought myself lucky to find a new job very quickly in field exploration in Southern Rhodesia.

However, that didn’t last long.

I was called into the Salisbury offices of the company involved to be told that, by being married to Maria, I was ‘bad’ for the company’s image and reputation. They asked: “How can we put you to work on land owned by a member of the Rhodesian Front?”

On the move again with big decisions to make

Interestingly, the company official who asked me that was a fellow Imperial and RSM alumnus. I resigned there and then, and have never forgotten the injustice of it all, but I look on the episode now as a true blessing in disguise. We left Africa reluctantly and went back to England.

Shortly after I was offered a job as a mine geologist on an underground copper mine in Quebec province in Canada and that was a great turning point. In Canada they weren’t worried about company images being sullied by us.

We remained at that mine for two years, after which we moved to the Canadian Northwest Territories, where I took up an opportunity as Chief Geologist on a small gold mine. We were there another two years, and I learned so much about mining and miners, I felt I was truly part of a fellowship of shared values. In mining operations, you never have to watch your back - someone always has it for you.

We had longed to return to Africa, and with the waning reserves of our gold mine, and the inevitability of having to make a move sooner rather than later, I looked to Africa for continuity, and got a job as Senior Prospecting Engineer on an opencast diamond mine in Ghana. It was actually not a good move - we loved the Ghanaian people, but couldn’t abide the air of colonialism dying hard that pervaded the mine society.

I was contracted there for a minimum of ten months but resolved to go when that time was up. The Australian mining industry was conducting a drive for geologists and engineers at the time, and it seemed a good bet. I had three job offers from Australian companies - it all felt like plain sailing, that is, until we encountered the strictures of the then White Australia policy. There were ways for us through it, but the requirements were as insulting as they were humiliating. We wanted no part of it and closed that door firmly.

New beginnings

Fate rose up to greet us once more. The GM who I had worked for at the gold mine in Canada informed me that the whole mine crew was moving to reopen and operate a copper mine in Southeast Ireland, and he wanted me to come as Chief Geologist. I accepted immediately. That was in July 1969.

We remained at that mine in Ireland for the next ten years. I was given a second title of Open Pit Superintendent, with responsibility for two small open pits. My job description from the GM was “do what you think is right”.

And endings (with more new beginnings)

Once again, the depletion of reserves and declining grades pointed to mine closure in the not too far distant future, and it was necessary to plan forward. I didn’t at all want to leave. But with the GMs encouragement, I began to look elsewhere.

A multinational oil company based in The Hague in the Netherlands was seeking to diversify into the mining industry and was looking for experienced technical staff. So, we joined it.

I had so many misgivings as to how I could ever contribute to such an organisation, but quickly came to realise that what I had was a facility with mines and miners and mining people in general. Expertise here was something I could provide to cut through all the grandstanding and open up reality.

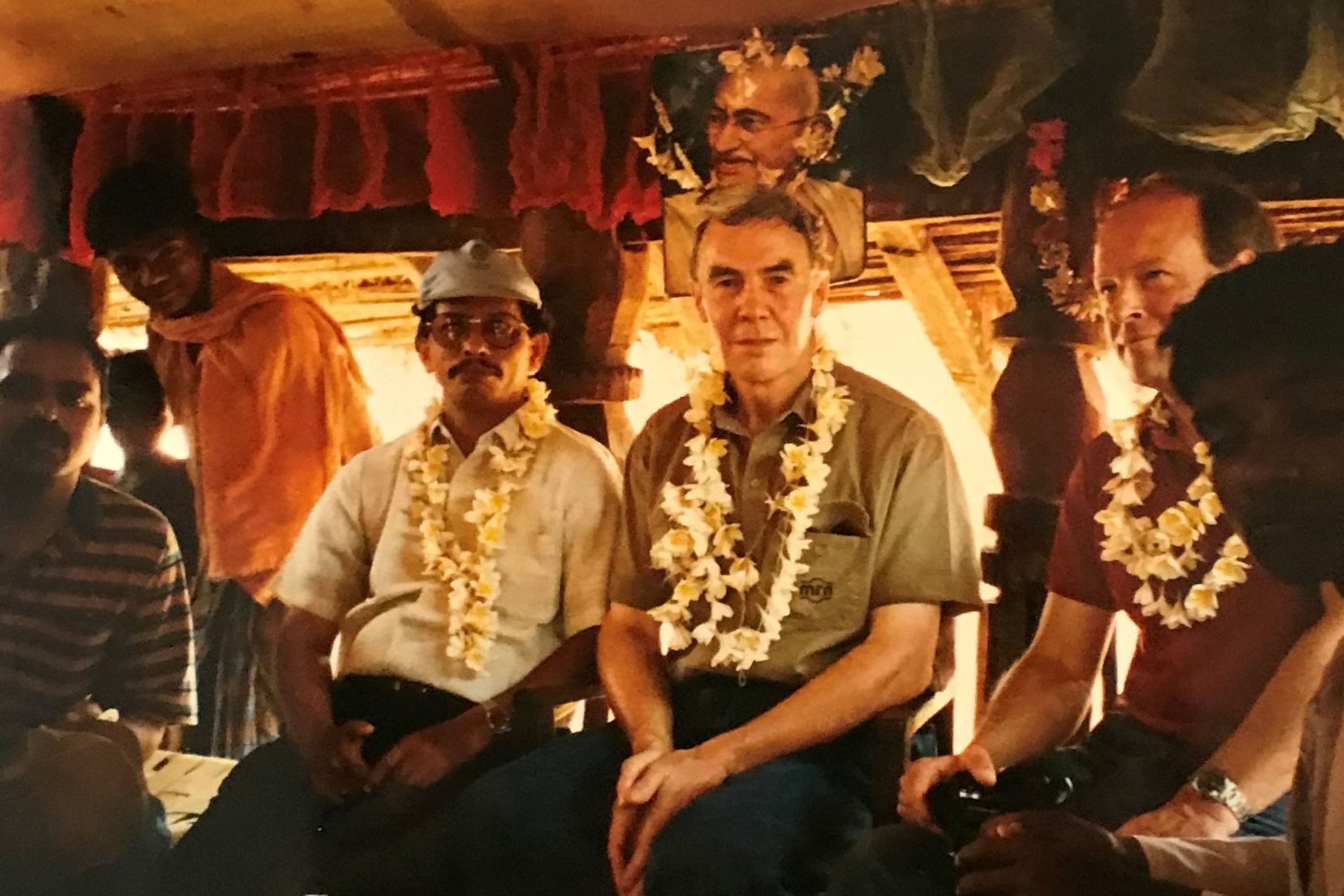

I travelled the world for this company for the next 22 years, to a host of mines and projects, working with and helping on the front line. This included a five-year assignment to a copper exploration project in Chile.

Time for a change

I left the work in 2001 and it was the right time for me to go. Indeed, a takeover of the company by an Australian mining major was likely, but I was also already past the statutory retirement age.

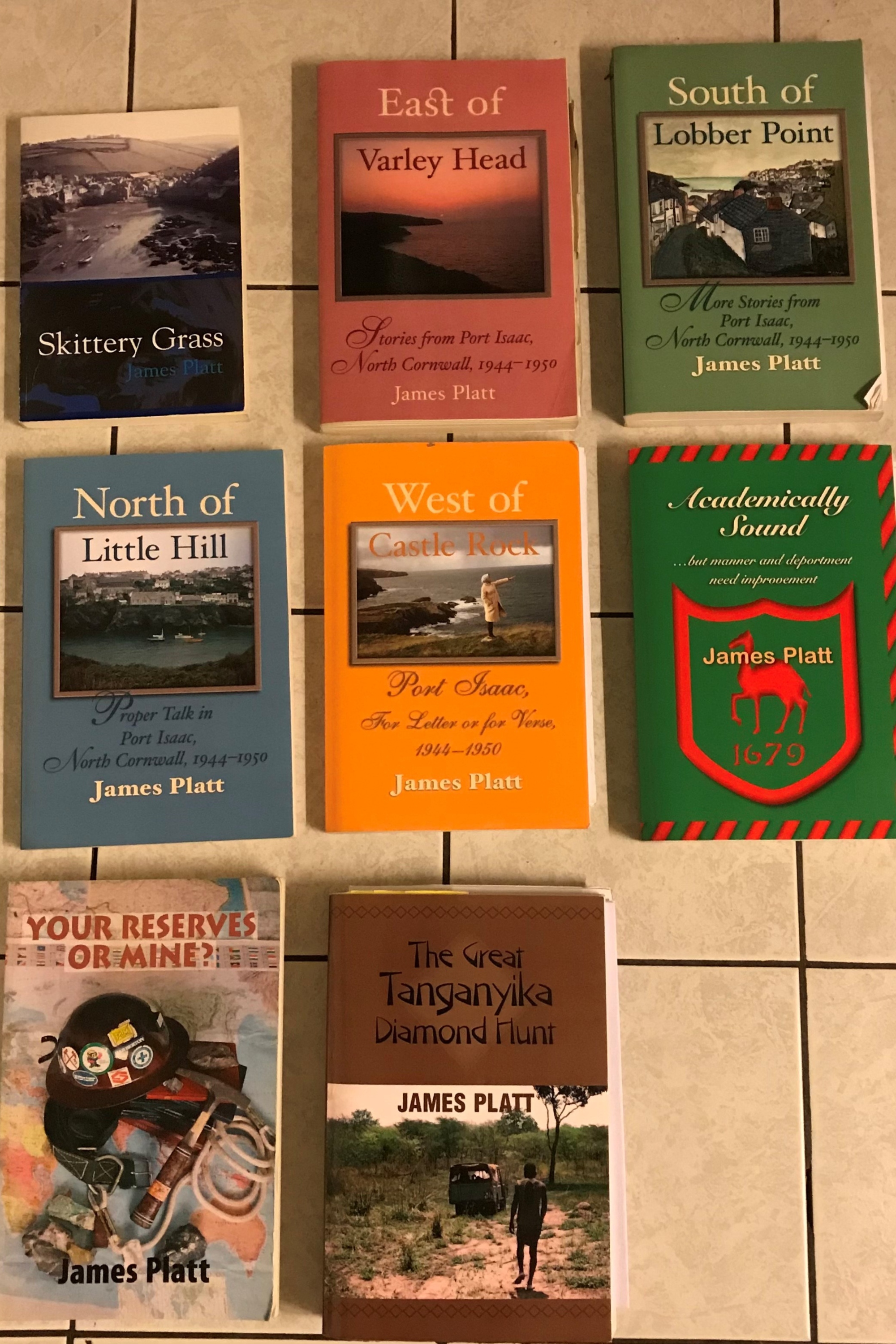

We chose to remain in the Netherlands after leaving and I began doing what I had always wanted to do. Namely writing, for my own sake and satisfaction, about my time of growing up in North Cornwall in the 1940s - the people, customs, activities and way of life.

Between 2001 and 2015 I wrote and self-published eight books, five on the North Cornwall connection, one on my years at grammar school, and two on some of my working experiences and travels. I have a ninth book in progress, but am not sure if, or when, that one will come to fruition.

My third and current, ‘career move’ came in 2015, in association with active initiatives by my granddaughter Lilly under the name of Lilly’s Plastic Pickup.

We are engaged with prevention of plastic pollution, clean-up activities, protection of wildlife, climate change awareness, respect for human rights, and justice in general. Our movement and action are ongoing.

Is there anywhere else you have lived?

The principal places in which I have lived, in the sense that I was based there, have been referred to above.

However, in the course of my work on mines and projects there are many places that I was privileged to visit for extended stays, frequently in the case of mining operations. These span:

- Europe - Norway, Sweden, the UK, France, Spain, Greece, and Albania

- North America and the Caribbean - Canada, the USA, Mexico, El Salvador, Jamaica, and Cuba

- South America - Venezuela, Colombia, French Guyana, Suriname, Brazil, Peru, and Chile

- Africa - Guinea, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Zambia, and South Africa

- Asia - India, Indonesia, Vietnam, South Korea, and China

- Australasia - Australia

These international visits gave me so much in the way of meeting, understanding, appreciating, and cherishing people, cultures, creeds, and societies for themselves. Confirming to me that there is far more that unites us all than should ever be allowed to divide us.

What does sustainability mean to you, and how have your work and interests connected with it?

To me, sustainability means doing whatever I can to help in building a clean, safe, and decent future for young people, as the torch is passed to them.

The mining industry, which has been the basis of my career, is an extractive industry, known for generating waste rock, toxic effluent, mill process tailings, dust, deforestation and so on. Where my area of responsibilities lay, we did what we could to co-exist in harmony with the local environment, generally, but not always with success. We tried and kept trying, and rehabilitation of any damage caused was the objective.

Sustainability’s key asset is people, and success is measured in what we can do in pulling together for the common good, not just for now, but for the future as well.

My current activities take place under the auspices of Lilly’s Plastic Pickup.

Tell us about Lilly!

Lilly Platt is my granddaughter, now aged 14. She lives in Huis ter Heide in the Netherlands and attends school in Utrecht. At the age of seven, she learned of the damage that plastic waste caused to the environment and decided to take matters into her own hands and devise her own contribution to eliminating plastic pollution at source.

On her own initiative she began picking up plastic litter, extending to litter in general in the area in which she lives. I joined the initiative, which she called “Lilly’s Plastic Pickup” as her assistant, and the campaign continues in the way it began to this day.

We would like to live in harmony with nature in a clean environment and respect for all forms of life is paramount to Lilly’s mission.

Lilly’s Plastic Pickup

Lilly’s Plastic Pickup can be found on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

We want to influence by example, by showing what can be done, even in a small way. We seek to set an example in maintaining a clean environment through the steady medium of voluntary activity in which we cover the streets, tracks, parks, and public facilities of our local area. This is always on foot, covering in the order of 10km per day, and collecting and cleaning the litter and discarded items that we come across. We cumulate the collection for a week then sort it into a range of categories for appropriate recycling.

In the six years that we have been doing this, the count amounts to between 800 and 900 items per week, or something like 250,000 items to date.

The categories of sorting are: cigarette packets, drink cans, plastic bottles, glass bottles and other glass, drink receptacles, balloons, single use plastics, face masks (now in decline), and miscellaneous, which is a separation of plastic, paper, and general rubbish.

Lilly juggles school with Lilly’s Plastic Pickup and other actions to protect the environment and raise awareness of mitigating climate change, through public speaking at national and international meetings (spanning the UK, Scotland, Norway, Italy, Austria, Canada, the European Parliament) and working alongside various organizations. She has received a number of environmental awards for her initiative. She is also an Ambassador for the Plastic Pollution Coalition.

A lot of people doing a little to take responsibility for their actions amounts to a good step forward. The real problem in making mistakes is that we fail to learn from them.

Lilly talks the talk and walks the walk, giving the example by doing. She is a testament to the passion and determination of youth, to whom the future belongs.

She believes in being kind to one another and to ourselves, and in doing the little things that can make a big difference. Along with others, Lily is intent on bridging the gap between speaking out and being involved. Young people can be included in a productive way and listening to them is essential.

When you reflect on your career, what things stand out the most?

Perhaps time tends to blur any downsides, I don’t really see any lowlights per se. There have been lows, but fate, or luck mostly tended to turn them into opportunities. There are things, sometimes stupid things, that I could or should have done differently along the way, but no road is smooth all the time. Mistakes are all to be learned from.

I have had severe bouts of malaria and went through years of high altitude induced physical and psychological sickness in Chile and after. But the former won me the lifetime prize of my wife, Maria, and the latter had me completing the exploration and initial development programme for what became a major copper mine.

I have worked on some projects that failed through lack of promise, and I’ve worked on others that made the grade. One highlight might be the reconnaissance exploration I did in northeast Botswana, which led eventually to the discovery of the Orapa diamond mine.

I am grateful to all that I met along the way, and I did my best to always be a worthy ambassador for Imperial and the RSM.

What is a typical day for you now?

Typically, I have to keep my house in order and manage all domestic and general, maintenance requirements and keep up with contacts and correspondence.

I do various voluntary and charity activities, for a long time concerned with the wellbeing of the elderly, although that has tended to recede as Lilly’s Plastic Pickup consumes more and more time.

Now and then I wish I was more social, but mostly I don’t. The time runs away, and there is never enough of it!

I plan to keep right on to the end of the road, and to not go gentle into that good night!

What would be your advice for current students?

My advice would be to treat everyone you meet with kindness and respect and empathy.

Learn from your mistakes, take responsibility for them, never hesitate to admit to them.

Never compromise your principles or integrity. Always give credit where it is due. Keep a daily journal - you never know when it may be useful to refer to it. If all of the above seems cliché ridden, let’s never forget that careers are formed by our relationship with people, and everyone has a story to tell.

What makes you proud to be an Imperial alumnus?

I belong to an organisation united in its fellowship, wonderful in itself, but in all ways greater than the sum of its parts.

Do you have a favourite quote or saying?

There are a number of quotes that I like and use, but if I had to choose one as my absolute favourite, it comes from one of my heroes, Mandy Rice-Davies, and is, “Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?”.

It exposes, in those few words, the lies, hypocrisy and lack of decency that permeates unearned entitlement today.

And at the risk of repeating a point, always important to me, I learned that a career is shaped by people. Again, not who they are, but what they are, and a friendly hand, a warm heart and kindness can open any door.

Final note

I am grateful for this opportunity to tell my story and offer some opinions along the way. Being an Imperial alumnus is like fine wine that gets better and better with time and is evermore an element of life that one wouldn’t be without.

What Jim would say to students:

"Never compromise your principles or integrity. Always give credit where it is due. Keep a daily journal - you never know when it may be useful to refer to it. If all of the above seems cliché ridden, let’s never forget that careers are formed by our relationship with people, and everyone has a story to tell."