Better sequence, better outcome

Words: Peter Taylor-Whiffen

Context

It’s a happy fact that millions of people now survive breast cancer. Many breast cancer patients who need a mastectomy also require radiotherapy – and request a reconstruction. Yet even the most expert treatment doesn’t just bring inevitable physical changes. It can also leave emotional scars leading to lifelong anxiety and mental health issues.

Background

Traditionally, hospitals have offered patients a mastectomy and then radiotherapy after surgery. In some centres, reconstruction is only offered at a later date, meaning many patients will have to wait – sometimes years – for a reconstruction; some don’t get one at all. Some hospitals offer reconstruction at the time of mastectomy, and then give radiotherapy to the chest wall (including to the reconstruction itself). However, this pathway can lead to complications such as damage to healthy tissues used to do the reconstruction – including shrinkage, firmness and loss of symmetry. Mr Daniel Leff, surgeon and Reader in Breast Surgery in Imperial’s Department of Surgery and Cancer, wondered if changing the sequence – giving radiation therapy to the breast before it’s taken away, and then doing the mastectomy and reconstruction – would be safe in the short term and reduce complications in the long term?

Methodology

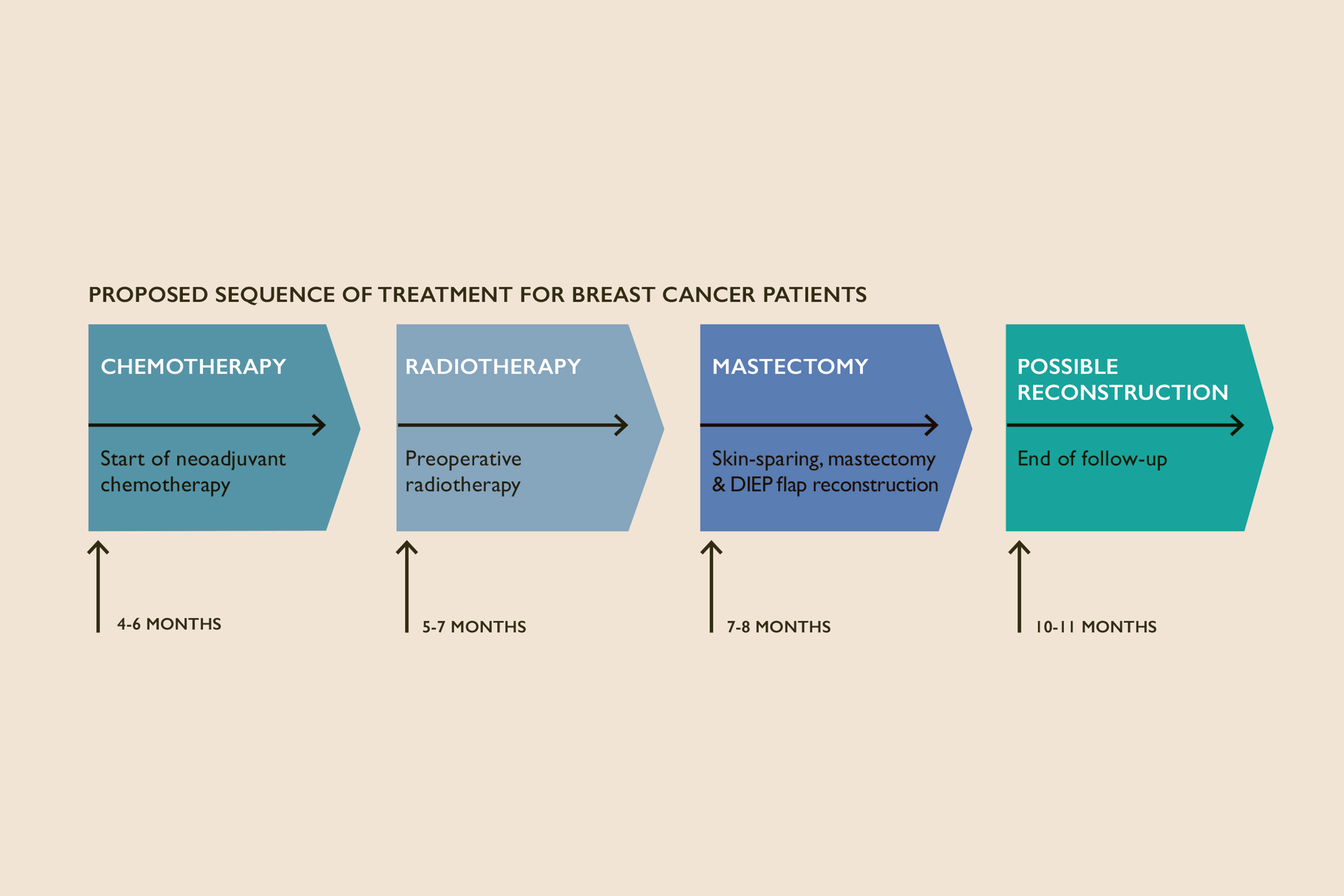

Leff, fellow Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Consultant Surgeon Mr Paul Thiruchelvam (MBBS Medicine 2000; PhD 2010) and their team joined colleagues at London’s Royal Marsden Foundation Hospital NHS Trust to recruit 33 patients dependent on their symptoms, size and spread of their tumour. They then gave the patients the radiation treatment first, followed by the mastectomy and reconstruction.

Findings

The study found that changing the sequence of the treatment was safe and technically feasible. The rates of complications were similar to those reported in other studies – four patients developed an open wound greater than 1cm, and one patient required a re-operation to tackle dead skin. “We also asked patients about their experience of reconstruction three months and 12 months after surgery and found a high level of patient satisfaction – and none of the patients’ cancers returned in or around the reconstructed breast 12 months after treatment.”

Outcomes

The alternative sequence was demonstrated as safe, but the results also suggested significant benefits. “It appears to be reducing recovery by a month,” says Leff, “meaning health benefits but also potentially cost benefits – we detected a reduction in longer term complications of the reconstruction and fewer hospital visits and procedures to correct downstream impact of radiotherapy on reconstructions.”

Leff emphasises that the small study was merely to look at risk in sequencing. “We’re not going to change practice from a paper that says it’s safe to change the sequence,” he adds, “but comparing long-term qualitative data to gold standard is now an urgent priority. As a clinical community we need to get funding to demonstrate that reversing the sequence has added advantages. The current order of treatment means that in many parts of the world women who need radiation therapy won’t get a reconstruction – we’re currently effectively denying them these quality of life benefits, which is utterly unfair. The alternative sequence is likely to enable more women to access reconstructive surgery, and may completely change their lives in survivorship.”

Mr Daniel Leff is a Reader in Breast Surgery working in the Department of Surgery and Cancer and Hamlyn Centre for Robotic Surgery.