)-CIFOR--tojpeg_1573570743962_x2.jpg)

The impacts of climate change will not be felt in the same way by everyone. Developing countries and people living in poverty will be particularly affected by increases in extreme weather events, worsening crop yields and sea level rise; and as the economy changes to create a zero-carbon society, some industries will end up transforming in a major way, which could put workers in those industries at risk.

This section looks at how issues of justice and fairness intersect with climate change. It explores why failing to address climate change would make it harder to address poverty, how a ‘just transition’ can be created for workers in industries that may disappear in a zero-carbon society, and why climate change is linked to questions of justice and ethics, from school strikes to international climate negotiations.

FAQ - climate action made 'fair'

- Does tackling climate change prevent the reduction of poverty?

- Will acting on climate change cause difficulties for some communities and industries as the economy changes?

- Do we have an ethical obligation to stop climate change?

The impacts of climate change do not affect everyone in the same way. Developing countries, and in particularly poor people in those countries, suffer disproportionately from floods, heatwaves, worsening crop yields and sea level rise, as they are financially less able to adapt to such changes[1]. This makes climate change a factor that threatens people’s ability to emerge from poverty.

Failing to address climate change would as such make it harder to address poverty[2]. If emissions are not reduced and the impacts of climate change become more severe, people in poverty will be worse off. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) considers the unfair distribution of climate change impacts one of its “main reasons for concern”; a risk that grows as global warming increases[3].

At the same time, eradicating poverty means ensuring that policies that aim to tackle climate change do not impose short-term costs on those people that are least able to afford it. It also raises the question of whether developing countries would be limited in their economic growth if they reduce their emissions immediately, as fossil-fuel based energy has historically helped countries towards faster development[4].

It is increasingly clear, however, that ‘growing first and cleaning up later’ is not an effective approach to economic growth in developing nations. Instead, addressing climate change is likely to create new opportunities for growth and jobs, aligning with other development objectives rather than challenging them[5].

For example, for energy consumers, constantly falling costs mean electricity from renewable energy is now often more cost-effective than electricity from fossil fuels. This is particularly the case in rural areas where local electricity demand is low and widely spread. Here, distributed energy solutions – such as community-led solar “mini-grids” – are often the cheapest and easiest ways to install sources of power and increase access to electricity, and they have health benefits such as bringing down air pollution levels as well[6].

As developing countries invest heavily in infrastructure to grow their economies, they also have a major opportunity to invest in sustainable assets up front. Infrastructure projects like energy systems are designed for longevity, which means building clean and resilient infrastructure now avoids the need to replace it later as part of the global effort to tackle climate change[7]. This makes the zero-carbon transition cheaper in the long run. At the same time, adapting infrastructure to the future risks of climate change will also make people in poverty less vulnerable to climate shocks[8].

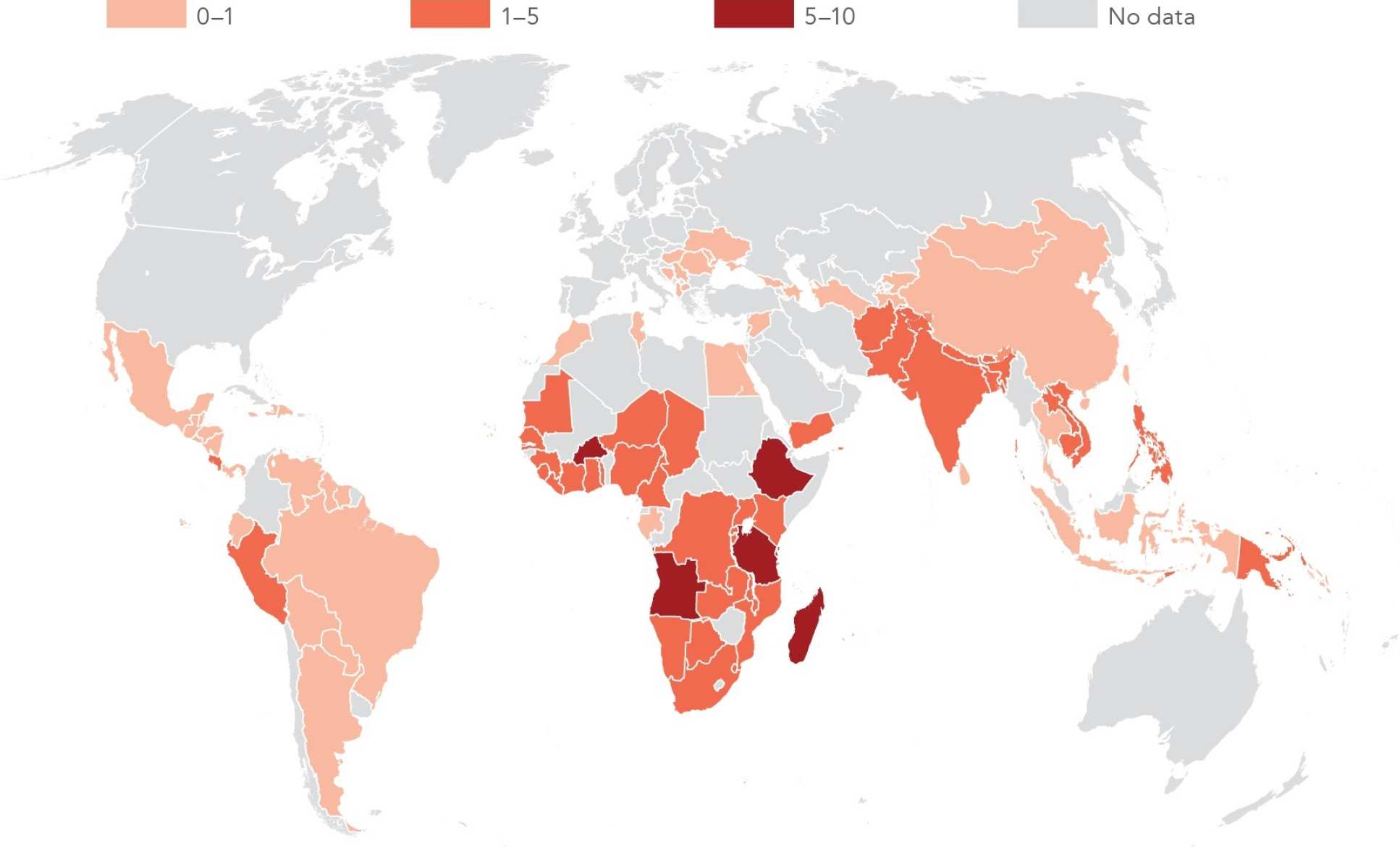

Figure: Climate change could raise extreme poverty rates substantially by 2030

Percentage point increase in number of people living in extreme poverty

References

[1] World Bank. (2016). Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty. Climate Change and Development Series. Washington, DC: World Bank.

[2] World Bank. (2016). Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty. Climate Change and Development Series. Washington, DC: World Bank.

[3] IPCC. (2014). IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: CUP.

[4] Fankhauser, S. and Jotzo, F. (2018). Economic growth and development with low‐carbon energy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(1), p.e495

[5] World Bank. (2012). Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathway to Sustainable Development. Washington, DC: World Bank

[6] Shindell, D. et al. (2012). Simultaneously Mitigating Near-Term Climate Change and Improving Human Health and Food Security, Science 335: 183–89.

[7] Pfeiffer, A. et al. (2016). The ‘2 C capital stock’ for electricity generation: committed cumulative carbon emissions from the electricity generation sector and the transition to a green economy. Applied Energy, 179, pp.1395-1408

[8] Fankhauser, S. (2017). Adaptation to climate change. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 9, pp.209-230.

To tackle climate change, it is necessary to cut greenhouse gas emissions drastically across all parts of the economy. This transformation presents major opportunities, with the Wold Bank suggesting that a zero-carbon economy will likely be more prosperous than a high-carbon economy in the long run[1].

However, managing the transition means recognising there will be winners and losers. Inevitably, some industries – such as the oil and gas sectors – will decline or majorly transform[2]. Workers in these industries, the communities where they live, and other businesses that rely on them, face risks if the transition is not carefully considered.

Some countries will also face greater difficulties than others, especially those that depend on fossil fuels. In India, for example, royalties from coal make up almost 50% of revenues for some states, which means the economy could be particularly hard hit from a transition to clean power[3].

This is why creating a just transition is so essential. To urgently act on climate change, the shift to a zero-carbon economy must bring everyone with it, and governments have an important role to play in creating policies that ensure this happens.

There are many lessons from previous industrial transitions on how to manage the shift, in particular for the fossil fuel sector. These show that implementing policies early can help to manage the decline of industries. Alongside a long-term vision to support growth in new industries in those regions, this can help avoid harming workers’ livelihoods and communities that rely on specific industries. Such a managed transition requires close collaboration between a country’s government, local authorities, businesses and labour unions[4].

Supporting affected workers through wage guarantees, pension rights, healthcare benefits, cash transfers and early retirement packages can also help smooth the transition in the short-term. in the medium term, government and business investment in skills and retraining for workers to enter new industries can help prevent industrial decline. In the long run, government and businesses can invest in education and innovation, and grow industries that create long-term prosperity in a green economy[5].

References

[1] World Bank (2015). Decarbonizing Development: Three Steps to a Zero-Carbon Future. Washington, DC.

[2] Fankhauser, S. and Jotzo, F. (2018). Economic growth and development with low-carbon energy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(1), e495

[3] Spencer, T. et al. (2018). The 1.5°C target and coal sector transition: at the limits of societal feasibility. Clim. Policy 18, 335–351

[4] Gambhir. A., Green, F. and Pearson, P. (2018) Towards a just and equitable low-carbon energy transition. Grantham Institute Briefing Paper no 26, Imperial College London

[5] Fergus Green & Ajay Gambhir (2019). Transitional assistance policies for just, equitable and smooth low-carbon transitions: who, what and how? To be published in Climate Policy

Climate change will harm both current and future generations by limiting their access to a safe and prosperous world. For this reason, stopping climate change can be viewed as an ethical duty for current generations to not profoundly damage the prospects of future generations[1]. Concepts of ‘justice’ are also debated intensely within international climate change negotiations, as the question of how to distribute responsibilities for tackling climate change is in many ways about deciding what is ‘fair’ based on individual countries’ circumstances, historical role in creating emissions and how vulnerable they are to climate change impacts.

The fact that future generations will be exposed to more severe impacts of climate change - but are not able to participate in decision-making today about how to limit and avoid those future impacts – can be viewed as a question of intergenerational justice[2]. This is the notion that as our present choices have the power to influence the options and possibilities available to future generations, we are obliged to consider the future impact of these choices.

A failure to decrease emissions of greenhouse gases today would mean future generations have no choice but to face severe and harmful climate impacts in the future. Young people across the world have protested this unfair distribution through global school strikes. Religious writings, such as from the Pope and Islamic leaders, have also pointed out that as humans are stewards of the Earth, we are responsible for protecting it as our common home for both current and future generations[3],[4].

In addition, international climate negotiations have taken into account the need for fairness between developing and developed countries in acting on climate change. The Paris Agreement states that its Parties are guided by “the principle of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances”. It also recognises “the specific needs and special circumstances of developing country Parties, especially those that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change”[5].

Deciding on a fair distribution of responsibility has been contentious in climate negotiations. Some countries, like the UK, have made a major contribution to global emissions since the start of the industrial revolution, while others, such as India, have only recently become major emitters. This difference creates a strong sense of injustice in developing nations, if they believe that they are being asked to make the same contributions to cutting emissions as countries with a larger historical responsibility for emissions; and which are also richer because of economic development and growth that led to these emissions[6].

Going beyond historical responsibility, the idea of ‘capability’ is another way to determine a fair distribution of action between countries. This approach suggests the most financially or technologically capable countries should be responsible for acting most urgently to reduce emissions. This gives less capable countries a reduced responsibility for immediately lowering emissions, and is another reason some suggest it is fair for industrialised countries to lead efforts to tackle climate change.

Both the UK’s large historical responsibility for causing climate change and its strong ability to act - as a wealthy, developed nation - are among the reasons why the Committee on Climate Change suggested it was fair for the UK to reach net zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050[7].

References

[1] Stern, N. (2014). Ethics, equity and the economics of climate change paper 1: Science and philosophy. Economics and Philosophy, 30 (2014) 397–444

[2] Wolff, C. (2009). “Intergenerational Justice, Human Needs, and Climate Policy” in Gosseries, A. and Meyer, L. H. (eds.), Intergenerational Justice. Oxford University Press

[3] Pope Francis. (2015). Laudato si: On care for our common home. Encylical Letter, Vatican

[4] IFEES (2015). The Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change. Paris.

[5] United Nations Treaty Series (2015). Paris Agreement.Paris, 12 December, 2015.

[6] Okereke, C. and Coventry, P. (2016). Climate justice and the international regime: before, during, and after Paris. WIREs Climate Change, 7:834–851.

[7] Committee on Climate Change. (2019). Net Zero – The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming. London, 2019.

Read more about these topics by exploring the explainers published by our sister institute, the Grantham Research Institute at LSE:

GRI explainers

Read more about these topics by exploring our background briefings:

[Image by Axel Fassio/CIFOR is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Published November 2019, last updated March 2022.

Find more FAQs

To read more explainers on climate change economics and finance, energy policy and international climate action, see the FAQs published by the Grantham Research Institute at LSE.