Fungi may not be at the forefront of people’s minds when they think of infectious threats, but disease-causing fungi have the potential to devastate or disrupt human health, wildlife, natural ecosystems, food security, and global trade policies. Because of their impact on these sectors, antifungals (including a widely used class called azoles) are used prolifically to treat both fungal diseases in the clinic and to protect crops in agriculture. However, such ‘dual use’ accelerates the spread of resistance across the globe and means that we are losing our first line of defence against opportunistic fungal infections in the clinic.

Fungi may not be at the forefront of people’s minds when they think of infectious threats, but disease-causing fungi have the potential to devastate or disrupt human health, wildlife, natural ecosystems, food security, and global trade policies. Because of their impact on these sectors, antifungals (including a widely used class called azoles) are used prolifically to treat both fungal diseases in the clinic and to protect crops in agriculture. However, such ‘dual use’ accelerates the spread of resistance across the globe and means that we are losing our first line of defence against opportunistic fungal infections in the clinic.

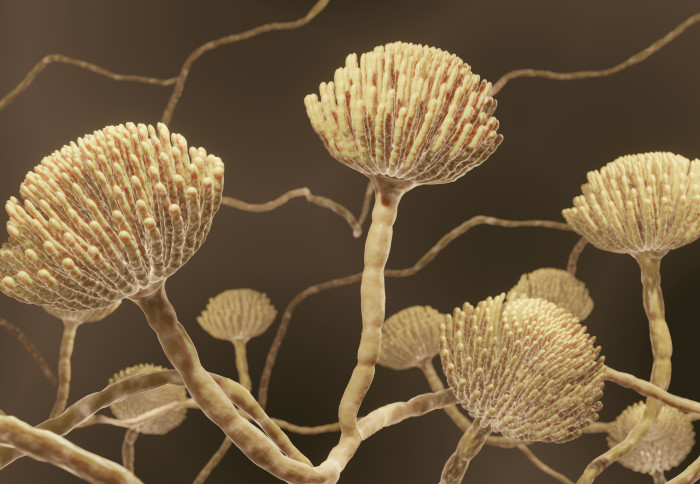

Imperial researchers, including Professor Mat Fisher and Dr Johanna Rhodes, are studying how resistance develops by examining the interplay between the environment (e.g., agriculture), amplifiers (e.g., farm or food waste disposal) and exposures (how and where humans, animals, and plants encounter resistant drug-resistant fungi). Using a genomic analysis of environmentally and clinically sourced Aspergillus fumigatus, a common mould found in the soil and air, they confirmed that people can acquire drug-resistant infections from the environment (Rhodes et al, Nature Microbiology 2022). This is a concern because it indicates that infections can be drug-resistant even before they encounter the people they infect. Recent work by the group using Citizen Science has demonstrated a landscape-scale exposure to this AMR threat in the UK (Shelton et al, Science Advances 2023).

Read the summary and the team’s research tracking spread of resistance using Citizen Science.