Three dimensional image of protein could herald new allergy treatments with fewer side-effects

Imperial scientists working at Diamond Light Source have solved the 3D structure of the human H1 histamine protein, which is responsible for allergic reactions like hayfever and food or pet allergies - News

Adapted from a press release issued by Diamond Light Source

23 June 2011

An international team of scientists has successfully solved the complex three dimensional structure of the human Histamine H1 receptor protein. This molecule triggers itches, rashes or swelling in the one out of every four people who suffer with hayfever or other allergic reactions to food or pets.

See also:

- Nature

- Diamond Light Source

- The Scripps Research Institute

- Kyoto University

- Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC)

Related news stories:

- UK team reveals all three structures of a single transporter protein

- Sparkling with success – Diamond fellowship awarded to Imperial life scientist

- Imperial College laboratory opens at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron

- Fight against hay fever and other allergies helped by new immune system discovery

Published in the journal Nature this week, the researchers' discovery opens the way for the development of a new generation of anti-histamine drugs that are effective against various allergies and do not cause adverse side-effects like headaches or vomiting.

The team of scientists comprised leading experts from Imperial College London, Diamond Light Source (the UK’s national synchrotron facility), The Scripps Research Institute in California, USA, and Kyoto University, Japan, amongst others.

Professor So Iwata, David Blow Chair of Biophysics at Imperial College London, a BBSRC Fellow and Director of the Membrane Protein Laboratory at Diamond, said: “It took a considerable team effort but we were finally able to elucidate the molecular structure of the Histamine H1 receptor protein and also see how it interacts with anti-histamines. This detailed structural information is a great starting point for exploring exactly how histamine triggers allergic reactions and how drugs act to prevent this reaction.”

H1 receptor protein is found in the cell membranes of various human tissues including airways, vascular and intestinal muscles, and the brain. It binds to histamine, which is an important part of our immune system, but in certain susceptible individuals this can cause an allergic 'over-reaction' to non-harmful substances such as in hayfever or food and pet allergies. Anti-histamine drugs work because they prevent histamine attaching to H1 receptors.

Dr Simone Weyand, from the the Division of Molecular Biosciences at Imperial, who conducted much of the experimental work at Diamond, said: “First generation anti-histamines such as Doxepin are effective, but not very selective, and because of penetration across the blood-brain barrier, they can cause side effects including sedation, dry mouth and arrhythmia. By showing exactly how histamines bind to the H1 receptor at the molecular level, we can design and develop much more targeted treatments.”

The research was technically challenging because membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to crystallise – a step that is vital in solving protein structures using a synchrotron such as Diamond Light Source. In a process that spanned sixteen months, the proteins were grown in cells at Kyoto University, then processed cell material was flown was flown to Professor Raymond Stevens at The Scripps Research Institute who leads the GPCR Network of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences' Protein Structure Initiative, and has developed powerful techniques to analyse membrane proteins and crystallise G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) funded by the National Institutes of Health Common Fund.

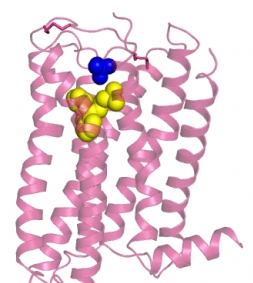

The crystal structure of human Histamine H1 receptor with doxepin

The crystals took around two months to grow and when each batch of around 100 was ready, they were frozen and flown to the UK. Here, Professor Iwata and Dr Weyand worked with Diamond’s scientists to analyse a total of over 700 samples using the Microfocus Macromolecular Crystallography (MX) beamline I24, a unique instrument capable of studying tiny micro-crystals using an X-ray beam a few microns wide.

Professor Stevens said: “A key aspect of our program is to collaborate with the leading researchers in the world so that we can uncover the mysteries of how GPCRs work. To fully understand this large and important human protein family will take a global community effort and the study of multiple receptors with d ifferent techniques and approaches. The collaboration with the Iwata lab is a great example of success made possible by joining forces; in this case, our work on histamine H1 receptor helps to advance the field as quickly and efficiently as possible."

Professor Iwata added: “Th e fact that we’ve managed to solve this structure in 16 months starting from pure protein is very exciting as it shows what can be achieved when a team of experts pool skills and experience in sample preparation, experimental techniques and data analysis. Having the Membrane Protein Laboratory situated inside the Diamond synchrotron itself is a major advantage for projects like this. We’ve benefited from rapid-access to the beamline and round the clock support for our experiments and data analysis work.”

Professor So Iwata, David Blow Chair of Biophysics at Imperial College London, a BBSRC Fellow and Director of the Membrane Protein Laboratory at Diamond

Professor Gerd Materlik, Diamond’s Chief Executive, said: “Solving this challenging structure so quickly is a significant achievement for Profs Iwata and Stevens, their groups and the I24 beamline team. I’m delighted that, in addition to providing access to cutting-edge research facilities, our scientists and technical experts have played an active role in this exciting project and I look forward to many future discoveries from the Membrane Protein Laboratory and the Microfocus MX beamline.”

This research was funded by the ERATO Human Receptor Crystallography Project from the Japan Science and Technology Agency and by the Targeted Proteins Research Program of MEXT, Japan; The National Institutes of Health (NIH), in the USA; and partly funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research and the Takeda Scientific Foundation.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Press Office

Communications and Public Affairs

- Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk