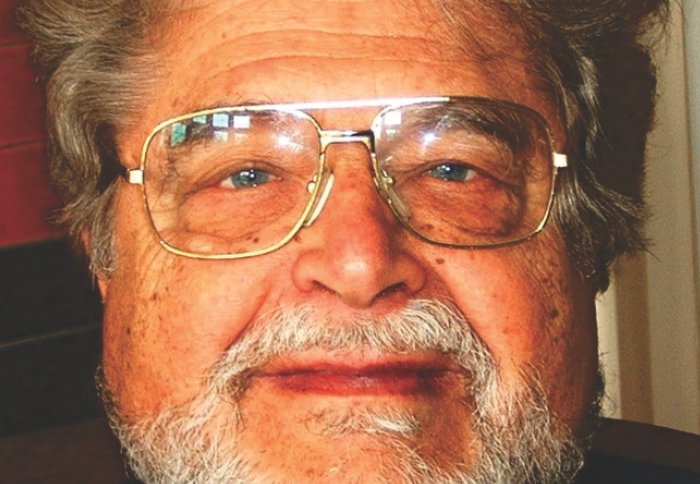

Tribute: Felix Weinberg

Felix Weinberg, Emeritus Professor of Combustion Physics died on 5 December aged 84 years. Professors Hans Michels and Rafael Kandiyoti pay tribute.

Felix Weinberg, Emeritus Professor of Combustion Physics died on 5 December 2012 at the age of 84. Professors Hans Michels and Rafael Kandiyoti (both Chemical Engineering) pay tribute to their colleague.

"It is time to say goodbye to ‘Felix’ — as Professor F.J. Weinberg FRS was known to all those around him.

Although many people were vaguely aware that Felix had survived the Nazi concentration camps as a boy, his ability to rise to the heights that he did with such a weight on his shoulders was rarely discussed. To us youngsters (now pushing 70 and beyond) Felix was just Felix — an outstanding academic who had simply always been there.

Many years ago, when it was suggested that he write up his experiences, Felix explained his reservations, noting that other survivors who had tried to recall those years of horror had become demoralised. In particular, he spoke of camp survivor Primo Levi, the Italian-Jewish chemist and writer, whose untimely death was interpreted as suicide.

Despite this, Felix’s memoir did slowly begin to take shape. And it turns out we have his friend, Ms Bea Green, to thank for this. According to Felix, she “…insisted that I owed it to my children and grandchildren to record this history, no matter how harrowing, because they ‘had the right to know’”.

In an opening passage of his memoir, soon to be published by Verso, Felix wrote: “I am 82 years old. If I do not start now, it will never be done. I can only hope that it is not too late already.” Luckily for the rest of us, he completed the proofs shortly before we lost him so suddenly.

In the memoir, we get glimpses of his early years, which he felt had given him that internal strength to keep going, on to a good life and a magnificent career. He wrote: “I had a very happy childhood. It came to an end too soon and too abruptly, thanks to Adolf Hitler, but I believe that it is the early years that count. They furnish the mind with a cocoon of security and contentment into which it can withdraw in times of hardship. That is why the children of dysfunctional families never stand a chance, in my view. My cocoon was well equipped with cozy memories and certainties of having been much loved and cherished.” When war came after this peaceful prelude, Felix lost many of his family.

He describes those harrowing years with open eyes. It must have been painful to revisit, but the story of his survival is a story of hope and the triumph of one young man over barbarism. In her foreword to Felix's memoir, Suzanne Bardgett, Head of Research at the Imperial War Museum, tells us that Felix rode his motorcycle for many years later, wearing a battered leather jacket “on permanent, if unauthorized, loan from one of the defunct Buchenwald guards”.

At the end of the war, he was reunited with his father in the UK. He had had no schooling since he was 12, could not speak English and had effectively forgotten how to write. But he soon caught up, and took up a place at the University of London to study general science, during which he developed a passion for physics that ultimately led to him becoming a Distinguished Research Fellow at Imperial with a national and international reputation in combustion physics.

Felix joined the College in 1951 as a Research Assistant in the Department of Chemical Engineering and Chemical Technology (as it was then called). He rose rapidly through the ranks as Assistant Lecturer, Lecturer and Senior Lecturer, to Reader in Combustion Physics. In 1960 he obtained his DSc from the University of London and within three years he was appointed to a personal Chair. Together with the spectroscopist Professor Dick Gaydon, he founded a school in combustion physics at the College that lasted for a quarter century and trained a number of researchers who now occupy top positions in the subject around the world.

Initially Felix’s interest was mainly focused on the structure of flames as dictated by their charge generation. In turn that led him to develop his specific understanding and expertise on how to analyze and control flame behaviour by electrical diagnostics and electrical field application. Early on in the boom of laser development he recognized the benefit that these instruments offered for rapid flame and plasma initiation and diagnostics. From the mid-eighties he was also occupied with the development of his heat re-circulating burner, for which he saw great potential for low-grade fuel combustion.

Felix’s eminence was recognized by an impressive collection of national and international awards from institutions and governments of major countries around the world. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society, the Institute of Physics and the Institute of Energy, and for years served actively on their subject committees. He was involved in organising and refereeing many international conferences, where he would invariably be present as a key-note speaker. When he was not there it was rarely possible to attend such meetings without being asked how Felix was.

For all his reputation, international esteem and the quality of his more than 200 scientific publications, Felix always came across as a modest and unassuming man. His lectures were the essence of informality, as he bent over a single transparency with multiple, simple hand-drawings and explained in a slow articulating voice, captivating students and conference attendees alike.

In his emeritus years he would attend Tuesday lunchtime group seminars almost without fail. With his sandwiches in front of him, he would listen to presentations by postgraduates or junior staff and always lead the Q&A sessions. He was dedicated to his students and worked hard to help them succeed. Indeed, some senior staff remember an incident where he came to the rescue of a post-graduate publicly criticized by an outspoken professorial colleague with the comment from Chinese philosophy “not to stamp on flowers if one wants them to grow”.

His spirited existence has uplifted the “… memory of my mother, my little brother and all the other members of my family who perished under horrific and degrading conditions in Nazi camps.” May they now all rest in peace.

To us, lives the memory of a brilliant scientist, an impressive presence, a meticulous scholar and above all, a decent and good man. We will miss him; we already do.

Professor Weinberg was featured in a special profile piece marking the College's centenary celebrations in 2007: http://www.imperial.ac.uk/centenary/professor_felix_weinberg.shtml

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Rafael Kandiyoti

Department of Chemical Engineering

Professor Hans J Michels

Department of Chemical Engineering