New strategy needed to fight non-communicable diseases

by Maxine Myers

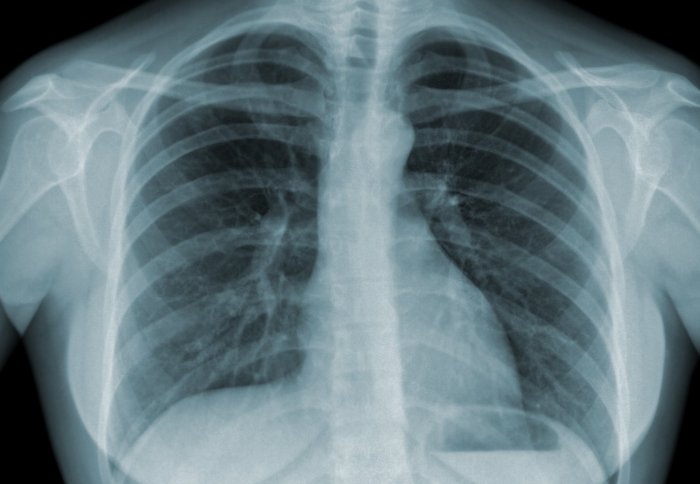

TB infected lung

Learning lessons from the fight against HIV and TB and addressing social and economic inequalities could help tackle non-communicable diseases.

These are the conclusions of researchers from Imperial College London in new studies presented and published this week.

Non communicable diseases (NCDs)—including heart disease, stroke, cancer and diabetes—have long been major causes of death and disability in developed countries, but are now reaching epidemic levels in the developing world. According to recent estimates, 34.5 million people died from NCDs in 2010, 65 percent of the 52.8 million deaths worldwide that year. By 2030, NCDs are expected to claim more than 50 million lives every year. The global economic burden of NCDs was estimated at US$6·3 trillion in 2010, rising to $13 trillion in 2030. The predicted cumulative global loss of economic output due to NCDs for 2011–30 is estimated at $46·7 trillion, with around half ($21·3 trillion) in low-income and middle-income countries.

Professors Majid Ezzati from Imperial College London and Rifat Atun from Imperial College Business School have jointly presented their latest results and ideas in two new studies as part of a major new series published this week in the journal The Lancet. The series highlights the critical importance of NCDs to a set of eight global development targets set by the United Nations, which come to an end in 2015.

It also proposes ideas that might help to achieve the new global target of a 25 percent reduction in preventable NCD deaths by 2025, which was made by the World Health Assembly in May 2012. Research carried out by Professor Ezzati and an international team showed that efforts to tackle NCDs will only succeed if Governments around the world focus on the health of the most disadvantaged people in their societies.

Social inequalities such as unhealthy diet, smoking and high blood pressure are risks factors that account for more than half of inequalities in major NCDs. However, according to Professor Ezzati’s team, NCD inequalities are also often the result of broader social and economic inequalities between rich and poor. These include a poor start in life, lack of education, poor living and working conditions, and lack of affordable and high-quality health care.

They emphasise that to reduce or eliminate these inequalities will require actions and policies across the social, economic, and health sectors.

Professor Ezzati and colleagues propose several key actions to reduce NCD inequalities, both between countries and within them, including:

- investment in early child development and high-quality education

- removal of barriers to secure employment for disadvantaged groups

- tax tobacco and alcohol, regulate their production and sales, and restrict their advertising or marketing

- improve financial and physical access of disadvantaged social groups to healthier diets, including fresh fruits and vegetables, healthy fats, and whole grains

- implement taxes, and regulate or restrict foods with high levels of salt, sugars, processed carbohydrates, and harmful fats

- improved access to high-quality primary health care for early detection and treatment

- universal health insurance or other mechanisms to remove financial barriers to health care.

In Professor Atun’s study, he outlined how building on the knowledge and partnerships forged from the global response to HIV and TB could help in the fight against the emerging NCD epidemic.

According to Professor Atun, this partnership is crucial because health systems around the world are currently unprepared to cope with the rising NCD burden, which often means that patients have to deal with two or more chronic medical conditions at once.

Professor Atun, from Imperial College Business School, said:“Most health systems have not been designed to cope with the multitude of new risks for NCDs and chronic illness. This burden will overwhelm the already stretched and weak health systems in most low-income and middle-income countries.”

“With HIV, visible global leadership, along with sustained advocacy by civil society, affected communities, and scientists enabled mobilisation of large financial investments to address the disease. However, lessons from the successful HIV response show that in embracing integration opportunities for NCD prevention and care, the challenge will be less clinical, but more managerial and political to create the right incentives for existing service providers in realisation of synergies to achieve greater health and equity. The narrow clinical focus, which has characterised the current response to the NCD epidemic, is unlikely to succeed.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Maxine Myers

Communications Division