Ageing of DNA linked to heart disease and cancer

by Sam Wong

Genes that regulate the tips of chromosomes have been found to affect risk of age-related diseases in a new study.

An international team of scientists including researchers from Imperial College London has found new evidence that links ageing of DNA molecules to the risk of developing several age-related diseases - including heart disease, multiple sclerosis and various cancers.

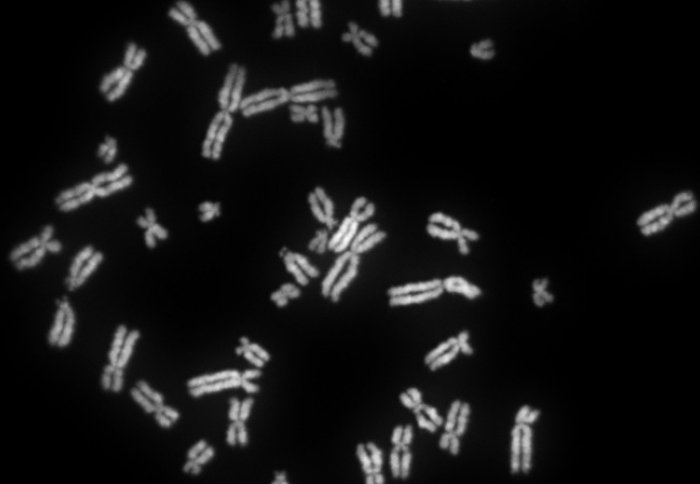

Telomeres – sections of DNA at the ends of our chromosomes – shorten each time a cell divides, so their length can be interpreted as a measure of biological ageing. However, it has not been clear whether the shortening of telomeres is responsible for causing disease, and whether people with shorter telomeres have a higher risk of diseases

The study, led by the University of Leicester, involved scientists in 14 centres across eight countries, working as part of the European ENGAGE Consortium. The research is published online in the journal Nature Genetics.

Dr Jess Buxton, from the Department of Medicine at Imperial analysed samples from over 5,500 of the study participants belonging to the Northern Finland Birth Cohort study. “We’ve shown that some people have genetic variants that mean they have shorter telomeres and are at higher risk of age-related disease,” she said. “The next step will be to look at how telomere length changes over time, and see whether telomere shortening rate can help tell us how well people are ageing. We will then be able to identify genetic and lifestyle factors that affect this process, leading to new ways of monitoring and hopefully extending the ‘healthspan’ of our increasingly ageing population.”

The research team looked at DNA from over 48,000 people and identified seven genetic variants that were associated with telomere length. They then examined whether these genetic variants also affected risk of various diseases. The scientists found that the variants were linked to risk of several types of cancer, including bowel cancer, as well as diseases like multiple sclerosis and celiac disease. The seven variants they identified were collectively associated with risk of coronary artery disease, which can lead to heart attacks.

The genetic variants are inherited, and so affect telomere length throughout a person’s life. The fact that the same variants are also associated with an increased risk of ill health in later life suggests that shorter telomeres are one possible cause of some age-related diseases.

Telomeres do not carry genetic information, but they protect genes from being damaged by deterioration at the ends of chromosomes. When telomeres become critically short, cells enter an inactive state and then die. Although telomeres shorten as people get older, individuals are born with different telomere lengths and the rate at which they shorten can also vary.

Professor Marjo-Riitta Jarvelin from the School of Public Health and Dr Alex Blakemore from the Department of Medicine also contributed to the study. “An important aspect in the future research is to explore how children’s early growth and experiences may have an impact on telomere length and ageing processes”, Professor Jarvelin said.

Professor Nilesh Samani, British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiology at the University of Leicester, who led the overall project, said: “These are really exciting findings. We had previous evidence that shorter telomere lengths are associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease but were not sure whether this association was causal or not. This research strongly suggests that biological ageing plays an important role in causing coronary artery disease, the commonest cause of death in the world. This provides a novel way of looking at the disease and at least partly explains why some patients develop it early and others don’t develop it at all even if they carry other risk factors.”

Dr Veryan Codd, Senior Research Associate at the University of Leicester who co-ordinated the study and carried out the majority of the telomere length measurements said: “The findings open of the possibility that manipulating telomere length could have health benefits. While there is a long way to go before any clinical application, there are data in experimental models where lengthening telomere length has been shown to retard and in some situations reverse age-related changes in several organs.”

Based on a news release from the University of Leicester.

Reference: V Codd et al. 'Identification of seven loci affecting mean telomere length and their association with disease' Nature Genetics 45, 422–427 (2013) doi:10.1038/ng.2528

Image credit: Abogomazova / Wikimedia Commons

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Sam Wong

School of Professional Development