Imperial reflects on 100 years of petroleum education

by Colin Smith

This year Imperial is celebrating 100 years of petroleum related research and education.

The College’s Department of Earth Science and Engineering is holding a celebratory conference that focuses on the future of petroleum geoscience and engineering, which has attracted industry leaders and academics from around the world. A special centenary dinner was held in the Natural History Museum on Monday 23 September to mark the milestone.

The College is establishing the Petroleum Centenary Fund that will provide scholarships, bursaries and work placements in industry, giving undergraduates and postgraduates from across the globe the chance to study at Imperial.

Professor Jan Cilliers, Head of the Department of Earth Science and Engineering, says: “Oil is vital to the world economy. It not only powers our ships, planes and cars, but is a key ingredient for making life saving pharmaceuticals, plastics and even fertilizers to help our crops to grow. Over the last 100 years Imperial students and academics have played a pivotal role in the growth and development of the industry and we are celebrating this milestone. We hope the establishment of the Petroleum Centenary Fund will be a lasting legacy that highlights our commitment to educating future generations of engineers.”

“The challenge for our petroleum engineers of tomorrow will be to ensure the extraction of oil from shale rock will be cost effective, sustainable and with minimal environmental impact.”

– Professor Al Fraser

EGI Chair in Petroleum Geoscience

Some of Imperial’s leading academics (below) in petroleum geoscience and engineering, who have organised the celebrations, reflect on the history, research, industrial partnerships and teaching that have helped to make Imperial a world leader in the field. They also talk about what the future holds for this field of engineering.

Dr Michael Ala, honorary senior academic, on how it all began

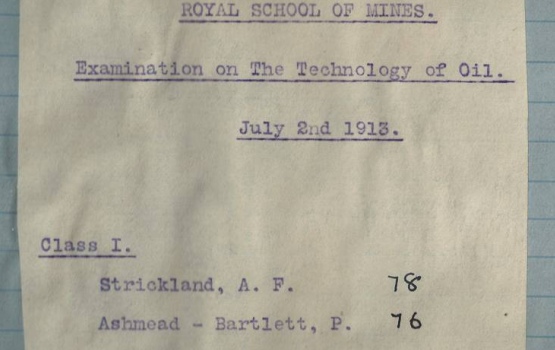

“Petroleum related studies first began at Imperial in 1911 when Professor William Watts, former Head of the Geology Department at the Royal School of Mines, set up a series of lectures on oil field geology. The course consisted of six lectures that cost students one pound and ten shillings, which is the equivalent of £1.50 in today’s money. It proved so popular that it was expanded in the 1912-1913 academic year, consisting of twelve lectures that were supplemented by laboratory work.

“In 1913, buoyed by the early success of these courses, Sir Alfred Keogh, Rector of Imperial (1910-1922), encouraged Professor Watts to establish the programme as a four year BSc Technology of Oil degree. The establishment of the course reflected the world’s increasing appetite for oil, as people swapped horse power for combustion engine power.

“The student population has grown exponentially since the class of 1913, which had just 5 students. Now there are around 550 students from 50 countries comprising 250 undergraduates, 150 MSc students and 150 PhD students. We predict that more than 20,000 students have graduated over the past 100 years.”

Professor Howard Johnson, Director of the Petroleum Geoscience MSc course, talks about teaching excellence

“Back in 1913 the learning experience was very basic as this field of science was only just beginning. Students had to examine by hand different rock and mineral samples using rudimentary microscopes. Fieldwork consisted of learning how to create geological maps in the search of oil.

“Today, students still need to acquire basic geological skills, but petroleum science has been vastly improved thanks to advanced analytical technology such as satellite and seismic imaging, devices that determine the chemical composition and mineralogy of rocks and advanced computer modelling that can simulate earth processes and how they affect oil extraction.

“Nowadays students have to be multi-skilled and capable of working as specialists in their own subject area, but also capable of working in multidisciplinary teams. These are skills highly valued in the industry. Thanks to relatively cheap air travel course work is also supplemented by amazing field trips with students visiting some of the world’s major oil producing industries that are based in countries such as Russia, the Middle East, South America and South East Asia.”

Peter King, Professor of Petroleum Engineering, discusses world class research

“In 1913 the world had an abundant supply of oil that could be pumped from easily accessible rocky reservoirs. Today, those reserves are depleted, which means that oil needs to be pumped from harder to access regions from deep under the Earth. This throws up a range of challenges for engineers and academics to overcome.

“Today, Imperial researchers are focusing on developing computer modelling and visualisation tools that would have seemed like science fiction to that first cohort of students. For example, Professor Martin Blunt uses CT scanners, normally found in hospitals for visualising patient innards, to characterise how oil flows through rock at the microscopic level. Understanding how oil flows through the gaps between the grains in the rocks enables new methods to be developed for improved extraction from more hard-to-reach places.

“My colleagues and I are also developing computer models that enable the industry to determine how oil flows in a reservoir on a large scale. A typical oil field can be the size of central London, costing billions of pounds to develop, so our modelling tools help the engineers to determine where to set up infrastructure such as oil rigs and piping, saving time and money in the process.”

Mark Sephton, Professor of Organic Geochemistry and Science, on space and oil recovery

“Our research in petroleum geoscience and engineering is also having impacts far beyond Earth. For instance, the same principles that are used to understand the geology of rocks in the search for oil are now being used by researchers such as Professor Sanjeev Gupta to search for signs of life on Mars.

“In my own research I have utilised chemicals that are normally used to extract organic matter from space rocks to improve oil refining. I proved that these chemicals called surfactants could be used to recycle the prodigious amounts of water necessary to process oil sand deposits and turn them into conventional petroleum.”

Professor Al Fraser, EGI Chair in Petroleum Geoscience, on links with industry

“The Department of Earth Science and Engineering has an annual research budget of £13 million. Two thirds of this is funded by businesses including many companies in the oil industry. Some of our partners include Shell, Statoil and Total. We are also working in collaboration with partners in the Middle East to make oil and gas extraction more sustainable. A team from Imperial, Qatar Petroleum and Shell are working on a ten year $US 70 million research project to improve oil and gas extraction and develop methods for storing harmful carbon dioxide emissions deep underground in depleted reservoirs in Qatar.”

Professor Fraser on what the future holds

“The first geoscience and engineering students who entered the oil and technology course were at the forefront of the conventional oil and gas exploration and refining. One hundred years on and today’s students stand on the threshold of a new and exciting unconventional oil and gas revolution - fracking. Extracting oil from shale via fracturing or ‘fracking’ rock is more costly than the production of conventional crude oil both financially and in terms of its environmental impact. The challenge for petroleum engineers of tomorrow will be to ensure this vital energy supply can be extracted cost effectively, sustainably and with minimum environmental impact.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Colin Smith

Communications and Public Affairs