Science from scratch: Will we ever create our own sun?

Ensuring a clean and plentiful supply of energy is one of the greatest challenges facing humanity. We look at one technology that might deliver this.

In this year’s film Star Trek: Into Darkness, Captain Kirk risks his life to save the Enterprise by entering the ship’s warp core.

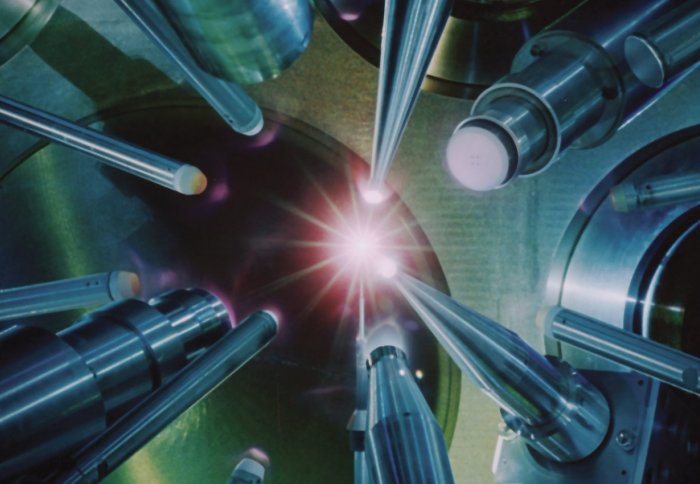

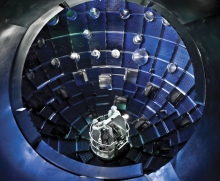

It may be Hollywood science fiction, but the scene was filmed inside the very real fusion target chamber of the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in Livermore, California.

Rather than inventing light speed travel, though, the team of NIF researchers are hard at work trying to make something equally incredible: pocket-sized stars.

All stars including our own sun generate their astounding energy through the process of nuclear fusion. Their intense gravity creates extremely high temperature and pressure at their cores, which squeezes together atoms of hydrogen gas fusing them into a helium nucleus. In the process, subatomic particles are expelled, such that the resulting mass is less than the sum of its original components.This extra mass is emitted as energy, in accordance with Einstein’s famous equation, E = mc2.

Researchers at the NIF use 192 precisely focused beams from the world’s most powerful laser to heat a pellet of hydrogen isotope, no bigger than this letter ‘a’, inside a gold cylinder chamber.

Researchers at the NIF use 192 precisely focused beams from the world’s most powerful laser to heat a pellet of hydrogen isotope, no bigger than this letter ‘a’, inside a gold cylinder chamber.

The laser beams hit the inner walls of the chamber, causing them to emit x-rays, which  implodes the pellet, creating the necessary extreme conditions for the hydrogen atoms to fuse.

implodes the pellet, creating the necessary extreme conditions for the hydrogen atoms to fuse.

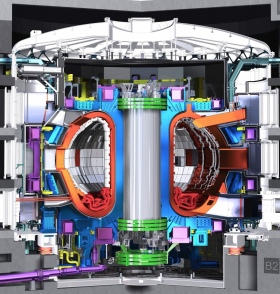

A rather different type of experimental fusion reactor is currently being built by an international team in Cadarache, France. Instead of using lasers, this ‘ITER’ reactor heats plasma gas in a hollow donut-shaped magnetic chamber to temperatures of around 100 million degrees – at which point the plasma may undergo fusion.

The challenge that both methods face as potential power sources is that they must produce more energy than they actually need to kick start them.

Realistically, it will be decades before fusion energy is lighting our homes and charging our smartphones. But we have to start somewhere, and these projects can also help scientists to peek into states of matter never before seen in laboratory environments.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Press Office

Communications and Public Affairs

- Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk