Behind the scenes tour at the US National Ignition Facility

Science Communication student Aliyah Kovner visits the NIF in California, where Imperial alumni lead a team trying to harness fusion power.

It’s 08:30 AM, several days after New Year, and I’m in a vast, grey and white warehouse in California. There are rows of metal pipes above me and the place is quiet and empty, save for the man I’m here to meet, who is carrying something in his hand.

On closer inspection I see it’s a charred tangle of metal and wires resembling burnt-out light bulb filaments. Later, I’m told that this is the remains of a cage that, for the briefest time, cradled a miniature star – ignited by those pipes, which are in fact amplifiers for the world’s most powerful laser.

On closer inspection I see it’s a charred tangle of metal and wires resembling burnt-out light bulb filaments. Later, I’m told that this is the remains of a cage that, for the briefest time, cradled a miniature star – ignited by those pipes, which are in fact amplifiers for the world’s most powerful laser.

No, it’s not the plot for a sci-fi B-movie – I’m actually in the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in Livermore and the scientist I’m here to see is Dr Mike Dunne, Director of Fusion Energy and Imperial alumnus (PhD Plasma Physics, 1995).

The NIF is arguably one of the most important science experiments on the planet, which, if successful, could permanently solve humanity’s energy woes and alleviate global warming pressures. Fusion is the process that the sun uses to generate enormous quantities of energy (see box, opposite page).

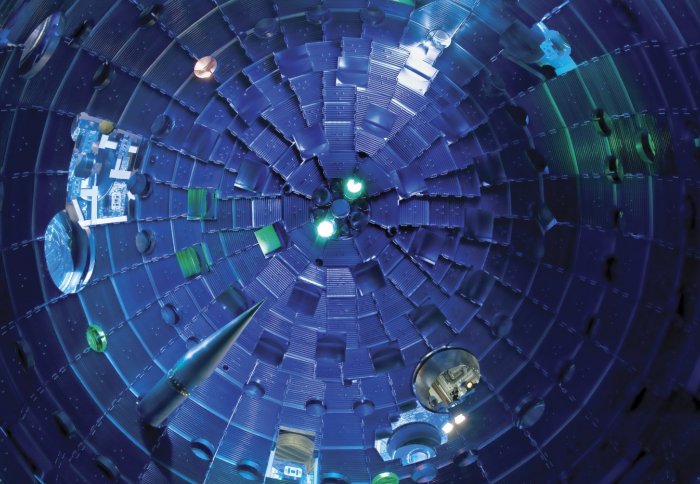

Scientists at NIF try to emulate this process by using 192 lasers beams precisely focused with lab-grown crystals to heat a pellet of hydrogen isotope, no bigger than this letter ‘a’, inside a gold cylinder chamber. The laser beams hit the inner walls of the chamber, causing them to emit x-rays, which implodes the pellet, creating the necessary extreme conditions for the hydrogen atoms to fuse.

Scientists at NIF try to emulate this process by using 192 lasers beams precisely focused with lab-grown crystals to heat a pellet of hydrogen isotope, no bigger than this letter ‘a’, inside a gold cylinder chamber. The laser beams hit the inner walls of the chamber, causing them to emit x-rays, which implodes the pellet, creating the necessary extreme conditions for the hydrogen atoms to fuse.

“There are people out there who will say: ‘fusion energy is a hundred year problem; it’ll never happen in our lifetimes’,” says Dr John Edwards, Associate Director for Inertial Confinement Fusion at NIF and another Imperial alumnus (PhD Plasma Physics, 1990). “It’s a standing joke that fusion energy is 50 years away – and it will always be 50 years away.”

Despite the scepticism held by some, the facility may be close to achieving ‘ignition’, the state at which the reaction of the fuel pellet produces more energy than the lasers need to kick start it. The drive to be the first team to achieve a self-sustaining fusion burn has attracted the world’s leading systems engineers and plasma physicists (many from Imperial) to Livermore since the NIF was first conceptualized in the 1990s.

'What drives most people in the programme is the potential impact this could have,' Mike Dunne

Mike is now confident in the system. He had hoped to reach the milestone last year, “but Mother Nature threw a few tricks in our way, and it’s taking a little bit longer,” he said. “But in some ways, that tells you all you need to know – people have been saying it’s decades off, yet we were disappointed we didn’t get there last year.”

Results from last year’s shots, as each experiment is dubbed, confirmed that the group’s ever-evolving system model is inching closer than ever to the correct parameters of laser pulse-shape and fuel composition that will result in ignition.

To speed up the timeline to energy generation, Mike and his team have collaborated with engineers from the power industry to create a design for a steam turbine to capture heat from the reaction. This means that once ignition is reached, fewer hurdles will stand in the way of adapting the system to feed into an electrical grid.

Even after a prototype has been built and tested, changing the infrastructure to support a working reactor would be a huge financial investment. Edwards (left) worries that the impact of current natural gas abundance on US political inclinations will delay the technology coming to fruition.

Even after a prototype has been built and tested, changing the infrastructure to support a working reactor would be a huge financial investment. Edwards (left) worries that the impact of current natural gas abundance on US political inclinations will delay the technology coming to fruition.

“The issue is that, in the meantime, we’re pumping all this carbon into the atmosphere, but people aren’t as concerned about that,” he said. A strong involvement and lobbying by public individuals and organizations could turn the tide. With the goal of reaching true fusion driving them forward, Mike and John draw on the skills earned during their time at Imperial.

The similarity of the cultures – both relying on multi-expertise integration and teamwork – has made the trans-Atlantic jump easier for the facility’s many Imperial transplants.

“It’s driven by a lot of esoteric science and engineering, but ultimately what drives most people in the program is the potential impact this could have,” said Dunne. “It’s incredibly motivating.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Press Office

Communications and Public Affairs

- Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk