How well do you really know your family tree?

One of the most profound questions in all of science is where we came from as a species. Science Commnuicaton student Aliyah Kovner looks for answers.

With the recent buzz around the higgs boson and innovative new treatments for cancer, it is easy to see science as a continuous march towards the future. Yet one of the most important breakthroughs of 2013 shed light on our own past and the origins of humanity.

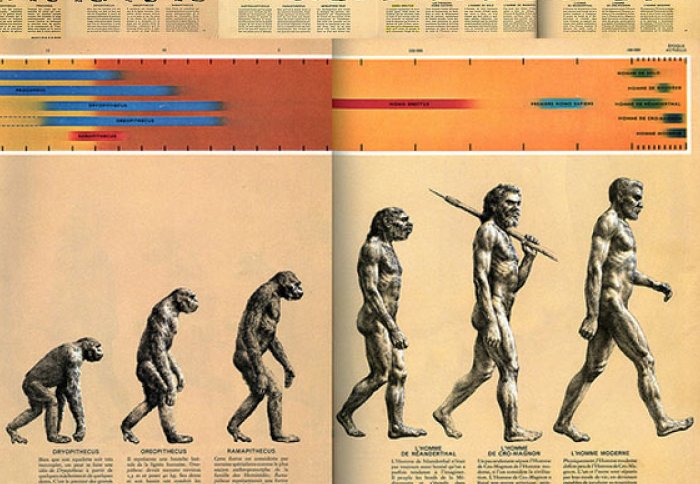

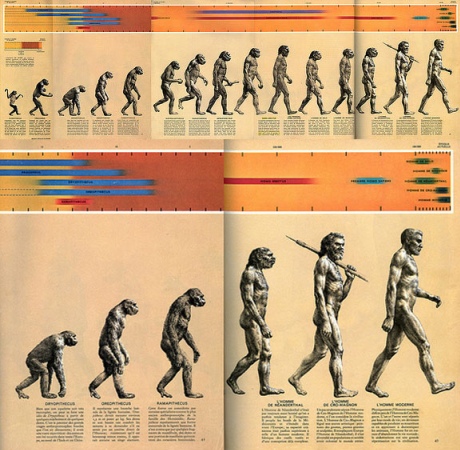

When we think of human evolution, we might conjure up that famous illustration – The March of Progress – where an ape starts to walk more and more upright in several stages, eventually resembling a modern human. In reality things were actually much more complex than this, with various branches and off-shoots of human-like species springing up – sometimes interbreeding with each other but often dying off altogether.

The often parodied 'March of Progress' illustration by Rudolph Zallinger from Early Man (1965)

In December, an international team announced that they had constructed a complete Neanderthal genome using DNA extracted from 130,000 year-old remains in a cave in Siberia. Neanderthals were an ancient branch of humans – a cousin species if you will – that went extinct some 30,000 years ago.

Using genetic mutation rates as a sort of calculator, researchers were able to determine that Neanderthals, Denisovians (another ancient species of human) and modern humans diverged from a common ancestor species just under 600,000 years ago, going their separate ways forever. Or perhaps not.

Comparing modern complete human and Neanderthal genomes at certain points suggests that the two species interbred and that traces of Neanderthal genetic code live on today in some humans. However, exchanges between the lineages were highly dependent on location. For example, Oceanic people appear to have between 3–6% Denisovian DNA and non-Africans may have over 2% Neanderthal DNA. As well as providing insights on what it means to be human, the findings paint a more detailed picture of Neanderthal society.

Neanderthals show evidence of some surprisingly modern features – such as lupus, depression, pale skin adapted for northern climates, and type II diabetes. Interestingly, the Neanderthal genes that live on most consistently in us are those for keratin, which is a protein in our hair, skin, and nails. We may have been better adapted to life on a changing planet, but Neanderthals had better coiffure.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Press Office

Communications and Public Affairs

- Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk