A closer look at Imperial's Centres for Doctoral Training

Inside the new wave of postgraduate centres that will train the next generation of science leaders to tackle big future challenges.

“Scientists and engineers are vital to our economy and society. It is their talent and imagination, as well as their knowledge and skills, that inspire innovation and drive growth across a range of sectors.”

These were the words of Universities and Science Minister David Willetts in November last year, as he announced renewed funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) for Centres for Doctoral Training (CDTs) across 24 UK universities to train over 3,500 postgraduates.

The aim is to produce scientists, engineers and leaders equipped to take on big societal challenges. For the postgrads themselves, that means more than just toiling towards a PhD, in relative isolation for three years. It means working alongside a tightly-knit cohort of peers and forging links with different departments, other universities and industrial partners. It also means students developing important transferrable skills – such as communication and outreach, team building, management and leadership.

The aim is to produce scientists, engineers and leaders equipped to take on big societal challenges. For the postgrads themselves, that means more than just toiling towards a PhD, in relative isolation for three years. It means working alongside a tightly-knit cohort of peers and forging links with different departments, other universities and industrial partners. It also means students developing important transferrable skills – such as communication and outreach, team building, management and leadership.

With the most recent announcement of extra CDTs, Imperial now has 12 Centres – more than any other institution (see box-out). Four of these centres have been running successfully for several years and their alumni are now having a real impact, putting into practice what they’ve learned.

Bridging disciplines

Since 2003 the Institute for Chemical Biology (ICB)-CDT has been operating at the interface between life sciences and physical sciences.

It takes a fresh approach to problems in biology, healthcare and agricultural sciences, developing new technologies and solutions from scratch – for example microfluidic chips for manufacturing artificial cells, new drug targets for parasite infection and techniques to studying single rare cells in isolation.

“There’s a growing need for innovation in this area and a new generation of multidisciplinary researchers who can drive that,” says Centre Director Dr Oscar Ces, adding: “We’ve been very successful in stimulating collaborations with industry and the clinic that have a real world impact.”

Over a decade on, the Centre now boasts a number of student-developed innovations that have attracted some £50million in follow-on funding; a raft of publications in top journals; and an impressive retention rate of 85% of alumni staying in science after graduating.

'We’ve been very successful in stimulating collaborations with industry and the clinic that have a real world impact' - Oscar Ces, CDT Director

The Centre recruits physical science graduates – chemists, mathematicians, physicists, engineers – and brings them up to speed with core biology in an initial Master’s (MRes) year including a nine month research project. Students then continue their research into their three-year PhD projects under at least two supervisors, including a biologist and a physical scientist.

“I loved chemistry and particularly the practical side of things but I found it hard to relate what I was doing in the lab to the wider world,” says student Kerry O’Donnelly, who’s project focuses on improving crop yields by boosting photosynthesis. “The ICB offered a rare opportunity: I got to take chemistry and apply it in the biological sense to see a problem through to the end.”

The overall structure of the Centre allows for more research freedom than is usual for a traditional PhD – and students even get to manage some of their own funding in order to pay for lab consumables or travel to conferences for example.

“You can’t get away with just one supervisor telling you exactly what to do all the time; you very much have to take the initiative yourself,” says student James Clulow.

The students also go through an entrepreneurship training programme in partnership with the Business School and Imperial Innovations, which culminates in a Dragons’ Den style competition (CDT-Den) where students bid for £20,000 of real funding by pitching a proposal that exploits the commercial potential of their research.

Winning CDT-Den 2010 team with presenter Evan Davies and Ali Salehi-Reyhani (right)

Dr Ali Salehi-Reyhani, now a postdoc at Imperial, is a former CDT student and joint winner of the 2010 CDT-Den for his team’s handheld device that instantly analyses mixtures such as groundwater or blood. This is being commercialised through spinout company anywhereHPLC.

“By the time you’ve completed your PhD you have ownership of your research that’s akin to a postdoc in his second or third posting. You become quite mature,” Ali said.

Free thinking

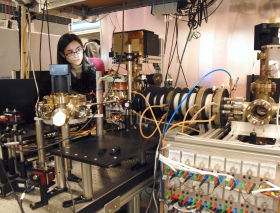

Another, quite different, Centre also now entering its second phase of funding is the Controlled Quantum Dynamics (CQD)-CDT. Quantum mechanics is an enormously successful theory that describes with incredible accuracy the world at the very smallest scales.

The really interesting thing about this area of science though, is that it seems to allow impossible things to happen – a single particle can be in two different places at the same time and two different particles can communicate instantaneously with each other despite being light years apart. Attempting to control such phenomena is one key aim of the CQD-CDT and may eventually lead to the development of a host of transformative technologies, such as quantum computing; ultra-secure telecommunications; and high precision measurement.

The really interesting thing about this area of science though, is that it seems to allow impossible things to happen – a single particle can be in two different places at the same time and two different particles can communicate instantaneously with each other despite being light years apart. Attempting to control such phenomena is one key aim of the CQD-CDT and may eventually lead to the development of a host of transformative technologies, such as quantum computing; ultra-secure telecommunications; and high precision measurement.

While these technologies remain some way off, Professor Myungshik Kim, Director of the CQD-CDT, says that it’s important to train the future scientists who might make these things a reality in the coming decades.

“I think the paradigm for technology development has changed: in the 20th century developers tested and experimented with products exhaustively in-house, then brought them to the market. Now prototypes are released much earlier, with the market helping to develop the final product. In a sense, our approach is similar. We certainly don’t have all the answers, but we’re advancing theory and application in tandem.”

One notable recent alumnus of the CDT is Dr Matt Pusey, who gained his PhD this October. Whilst at Imperial, Matt wrote a paper in Nature Physics that caused quite a stir. It sought to refine the famous Schrödinger equation, which describes all the possible locations that a single particle can be located at any given time. The paper was picked up in blogs and websites all over the world, with one top US physicist commenting: “I don't like to sound hyperbolic, but I think the word 'seismic' is likely to apply to this paper.”

Matt is now a post-doctoral researcher at the Perimeter Institute (PI) in Canada – a mecca for theoretical physicists pondering the really deep questions about reality. Matt says the freedom that the CDT encouraged set him up well for his burgeoning career.

Matt is now a post-doctoral researcher at the Perimeter Institute (PI) in Canada – a mecca for theoretical physicists pondering the really deep questions about reality. Matt says the freedom that the CDT encouraged set him up well for his burgeoning career.

“The fact that the money was attached to you rather than the individual project changed the dynamic and meant that you were more in control of your research. That’s the same kind of environment I work in now at the PI, where I’m centrally funded, rather than being attached to a specific fellowship.”

Director Myungshik is also keen to point out that CQD-CTD alumni who do not wish to pursue a career in the field are still well prepared. Because quantum mechanics challenges many of our most basic assumptions about the world we live in, it can instil in its practitioners true freedom of thought and a willingness to challenge orthodoxy. That’s important in business, politics and even art, Myungshik points out.

“You don’t have to see things in absolute terms and that’s a very valuable approach,” he says.

Perfect fit

The strategic aims of the CDT programme match the College’s own mission — championing world class research with an eye to applications in industry, commerce and healthcare. Which is why from October the Imperial CDT family will grow quite substantially.

One of the eight new centres, the Neurotechnology for Health and Life-CDT, will look for novel ways to tackle brain-related illnesses that affect more than two billion people worldwide. Much like the Institute for Chemical Biology-CDT it will operate at the interface between biology and physical sciences, to develop computational brain models, biosensors, brain-machine interfaces and neural prosthetics.

“In effect we’ve been planning for this for three or four years and we borrowed from the ICB’s model because its works well and because like them we are very interdisciplinary,” says Centre Director Dr Simon Schutlz.

In common with the ICB, students will be brought upto speed with biology, specifically neuroscience, in the first year. “They’re going to be doing a human brain dissection in their first week – as engineers; we’re going to take them out of Kansas!” Simon adds.

There is also a course in the MRes year on the ‘social and ethical implications of neurotechnology,’ which will help to give the students a wider perspective on their research.

The long-term legacy of the CDT programme looks set to be a whole generation of very well-rounded science professionals ready for anything the world throws at them.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Andrew Czyzewski

Communications Division