Researchers call for new evaluation methods to assess malaria programmes

Malaria testing being conducted in Swaziland. Credit: National Malaria Control Program

Researchers have developed a new way to evaluate malaria elimination programmes to enable valuable initiatives to continue to receive support.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) currently defines malaria elimination as the absence of locally acquired malaria cases over three years. Although an excellent target, many programmes cannot attain this goal because malaria can be ‘imported’ by infected people travelling into a region from abroad.

In this week’s Science, researchers from Imperial College London, Institut Pasteur Paris and other organisations have called for new methods to evaluate malaria programmes. Franca Davenport asks one of the authors, Dr Tom Churcher from the School of Public Health at Imperial College London, about the need for new evaluation methods and the possible advantages of their proposed new approach. Tom Churcher is based at the MRC Centre for Outbreak Analysis & Modelling and is part of the Malaria Modelling research group.

What are the challenges in evaluating malaria elimination programmes?

The WHO has provided useful milestones to help countries chart the path towards malaria elimination. However, there is a huge gap between a country entering what is called an ‘elimination phase’ and actually reaching elimination where it is very difficult to measure how successful the programme is and assess whether it’s on target. Currently elimination is defined as a country reducing the number of locally acquired cases to zero for a 3 year period. This is an incredibly admirable target to aim for but also one that is difficult to attain for many countries - not only because of the challenge of achieving zero infection but also because malaria may be continually reinvading from abroad.

These imported cases and the small number of local cases that they invariably cause means many programmes can be judged to be ineffective when in fact they may be making good progress. In the 1950s there was a global push to eliminate malaria but unfortunately it failed for various reasons and, as a result, there was a reduction in investment in malaria control. In fact it’s often been said that it didn’t eliminate malaria but it did eliminate the malaria funding. It would be terrible if a successful programme was halted because it was falsely perceived as being ineffective so it is vitally important that we develop more sensitive ways of assessing malaria elimination to show just how good these programmes are.

How do we currently evaluate malaria programmes?

We believe we need something more sophisticated to accompany the WHO definition: a way of putting the successes of the programme into the local context.

– Dr Tom Churcher

Lecturer in Infectious Disease Dynamics

Currently the approach is very black-and-white in terms of judging success based on whether the disease is eliminated or not. This makes it hard for countries which receive a large number of cases from abroad and who might have eliminated malaria if these importations ceased. We believe we need something more sophisticated to accompany the WHO definition: a way of putting the successes of the programme into the local context. There is a new surge and scale-up of elimination programmes but our fear is that unless we can show this huge increase in investment is actually achieving results then these elimination programme will suffer the same consequences as before. This could put the future of disease control in jeopardy. So we think it’s important to evaluate programmes more appropriately to ensure we don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater if campaigns don’t reach complete elimination and so that we get valuable data on which interventions are effective and why.

What is the alternative evaluation approach that you propose?

The concept behind our approach is not new – people have been talking for some time about the need to take into account the fact that malaria is often brought into a country from abroad so, even if a programme is effective, the number of recorded malaria cases do not truly represent the work of the programme. What we have done is use a simple approach to translate this concept into a practical tool that uses the ratio of the number of imported cases to the total number of cases. If this ratio is above a certain threshold - i.e. the contribution of imported cases is relatively large - then malaria can be considered to be controlled and nonendemic (see sidebar for distinction between endemic and nonendemic)

How do you determine this threshold?

The threshold is based on the reproductive number, which is a value epidemiologists love but generally isn’t used. It is a very intuitive number which basically represents the average number of malarial cases caused by every case of malaria. If the reproduction number is greater than one every imported case results in more than one other local case in the next generation and the epidemic will carry on spreading, but if every imported case causes less than one local case the disease will disappear.

Why do you think this approach is better?

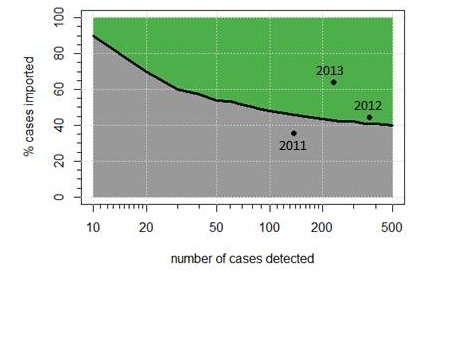

We don’t necessarily think it’s better but it does allow us to take into account the fact that malaria ‘travels’ with people. The method has several advantages. Firstly it takes a more nuanced approach to this very tricky area of evaluation, rather than simply deciding on the basis of there being no malarial infection for three years. Secondly the threshold we propose takes into consideration the sample size and the inevitable difficulties surrounding small numbers, so the approach counteracts the possibility that reaching this threshold could just be chance (see figure).

Percentage of imported cases required to confirm that endemic malaria transmission has been halted

Lastly and perhaps more importantly this method can be used easily in the field to evaluate programmes and we have also developed a simple Excel spreadsheet into which the data can be inputted.

You applied the approach to elimination programmes in Swaziland in the Science article – what did this show?

Swaziland has run a very effective elimination programme since 2008. This is helped because it is a small country at the edge of the malaria zone but also because they have invested heavily in this area. However the country also has a large number of imported malarial cases, for example migrant workers returning from Mozambique. Using data on the number of confirmed cases and on whether the person had been travelling in endemic regions before gettingthe disease, our analysis showed that although the number of cases increased from 143 to 377 in the period 2010- 2011, the percentage of imported cases also increased from 36 per cent to 45 per cent. Though there were more reported cases in 2011 our approach shows that the programme was actually more effective and that it is likely that malaria is no longer endemic. Using standard definitions of elimination the campaign would not have been seen as successful, but our new approach deemed it to be effective to eliminate malaria if importations stopped. In 2012 the programme proved even more successful, with the number of cases dropping to 229 and two thirds of these being imported.

How do you hope the approach will be used in the future?

The idea would be for people to use this approach in the field and we’re in discussion with malaria surveillance programmes to see if they would like to consider this method. At the moment countries just report number of cases but this would allow a more detailed picture to develop and inform public health approaches. For example if we can ascertain if there is regular importation of disease and transmission dies out quite quickly then there may be little advantage in giving out more nets or increasing insecticide spraying. Instead what could help is targeting the mobile populations that reintroduce malaria as they enter the country.

Dr Tom Churcher is a Lecturer in Infectious Disease Dynamics at Imperial College London.

Reference: Churcher et al. ‘Measuring the path toward malaria elimination’ Science 2014.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Franca Davenport

Communications and Public Affairs