Map of hepatitis C strains should help eradication efforts

by Sam Wong

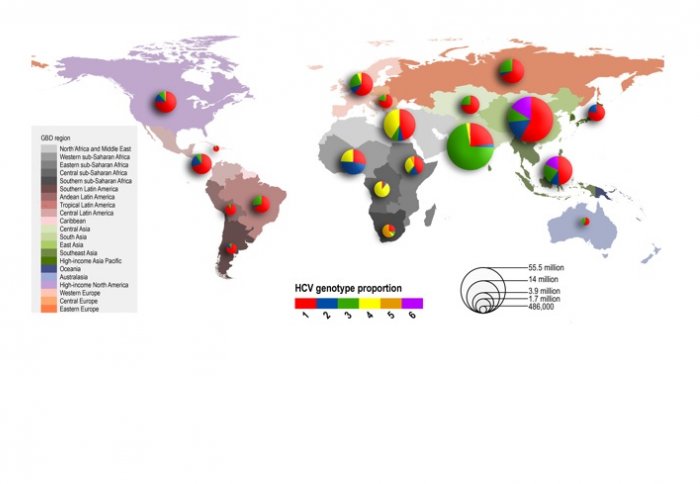

The researchers produced a map showing which strains of hepatitis C were most prevalent in different regions.

Researchers have for the first time mapped the global distribution of hepatitis C strains, creating a crucial resource in the fight to eradicate it.

An estimated 185 million people are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide. A significant number of those who become infected will go on to develop liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, and up to 500,000 people die each year from liver diseases related to the virus.

Hepatitis C can be cured, and a number of new, dramatically more affordable drug therapies with minimal side effects are set to become available over the next decade. With efforts to create a vaccine also showing promise, the prospect of eradicating the disease is now within sight.

However, the virus has six common strains, or genotypes, which respond differently to different treatments and vaccines. Knowing which strains are common in which areas is essential for planning eradication campaigns.

In a paper published today in Hepatology, researchers from the Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford and Imperial College London provide the first comprehensive survey of hepatitis C genotypes across the world.

If we can learn from the lessons of HIV/AIDS, mass production of generics can save millions of lives,

– Dr Graham Cooke and Dr Andrew Hill

By combining data from over 1,200 studies representing 90 per cent of the global population, the researchers found that while genotype 1 is the most prevalent worldwide, the other genotypes together make up more than half of all hepatitis C cases.

Dr Graham Cooke, a joint senior author of the paper from the Department of Medicine at Imperial College London, said: “Until now it has been incredibly hard to deliver hepatitis C treatment in regions without a good health infrastructure. New hep C treatments make things much easier but we need to be sure we have the right drugs available, and affordable, depending on which strains of the virus are present in each country. The data in this paper shows us the challenge those drugs need to tackle. We can now work out how to make them affordable.”

Professor Oliver Pybus, of the Oxford Martin School’s Institute for Emerging Infections, said: “This is a very exciting era in the treatment of hepatitis C, with a raft of new drug treatments in development. Our work shows where some genotypes are common and where they’re rarer. It’s extremely important for eradication and vaccine programmes to have access to this information.”

Dr Ellie Barnes, a Principal Investigator at the Institute for Emerging Infections, added: “As a world we should be thinking about how we can eradicate this virus. There are new drugs and vaccines in late stage development. But you’ve got to know where the different genotypes are in order to tackle hepatitis C in the most cost-effective way.”

In a recent article in Science, Dr Cooke and Dr Andrew Hill of the University of Liverpool argue that new hepatitis C drugs should be priced affordably in the same way that HIV treatment was made available to millions.

"If we can learn from the lessons of HIV/AIDS, mass production of generics can save millions of lives," they wrote. "This has been an inspiring medical success story which need not stand alone but can be repeated, even more rapidly, for hepatitis C."

Based on a news release from the Oxford Martin School.

Reference

Messina, J. P., Humphreys, I., Flaxman, A., Brown, A., Cooke, G. S., Pybus, O. G. and Barnes, E. (2014), Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. doi: 10.1002/hep.27259

Andrew Hill, Graham Cooke. ‘Hepatitis C can be cured globally, but at what cost?’ Science 11 July 2014: Vol. 345 no. 6193 pp. 141-142 DOI: 10.1126/science.1257737

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Sam Wong

School of Professional Development