Rosetta gears up for comet's dramatic solar approach

The Imperial-designed plasma sensor on board the Rosetta spacecraft is preparing to measure heightened activity of comet 67P as it approaches the Sun.

It follows the successful landing of the Philae daughter craft on Wednesday 12 November, which despite operational challenges, including the failure of the harpoons intended to stabilize the craft, managed to gather surface data on 67P and return it to the mothership.

While not directly involved in Philae, the Imperial-led Rosetta Plasma Consortium (RPC) package of instruments did prove important in the nail-biting descent, as principal investigator Chris Carr (Physics) explains.

“Our magnetometer sensor on the Rosetta orbiter, which measures the magnetic field around the comet, was compared against the magnetometer sensor on Philae,” he said. “In the end this information turned out to be really crucial in diagnosing the final orientation of the lander, since the two magnetometers were used like compasses to understand the rotation and pointing direction of Philae.”

On Saturday 15 November Philae went into hibernation owing to a lack of sunlight reaching its solar panels - a consequence of the unplanned landing in a shaded area of the comet. Engineers at the European Space Agency (ESA) are still leaving open the possibility that Philae might be woken up if its solar panels start to receive more sunlight as the comet approaches the Sun.

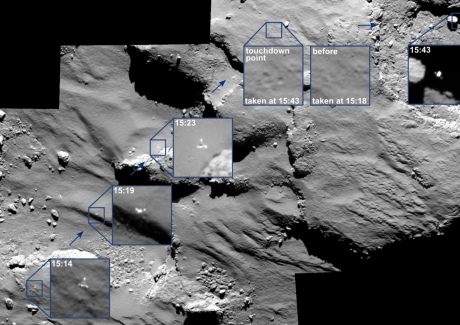

Composite image showing Philae's bouncing journey before coming to rest on the comet (ESA)

For Rosetta and the RPC specifically though, the mission continues apace, and they will now investigate the plasma environment around the comet, and how this interacts with the solar wind – the charged particles that stream constantly from the Sun. The comet’s plasma derives from vaporised volatile compounds on the comet’s surface that are ionised by solar ultraviolet radiation. It is expected that the plasma density will increase as the comet makes its approach.

“As the comet comes closer to the Sun, the science gets more and more interesting from a plasma point of view. However, we’ve already started to see some unexpected data, for example the appearance of low-frequency waves of around 40 millihertz in the magnetic field, which we can’t explain at present,” Carr said.

The Rosetta orbiter mission will continue until the comet reaches its perihelion – its closest point to the Sun - in August next year. The RPC team will track the development of the comet’s ionosphere, testing their prediction that the comet’s environment eventually deflects the solar wind, preventing it from burning up.

“There was a tantalising glimpse of this when the ESA Giotto spacecraft flew past comet Halley, 600km from the nucleus in 1986,” Chris said. “But with Rosetta we’ll be in orbit for a whole year, so we’ll be able to observe this development direct

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Andrew Czyzewski

Communications Division