Fossil fish reveals sharks lost bony armour early in their evolution

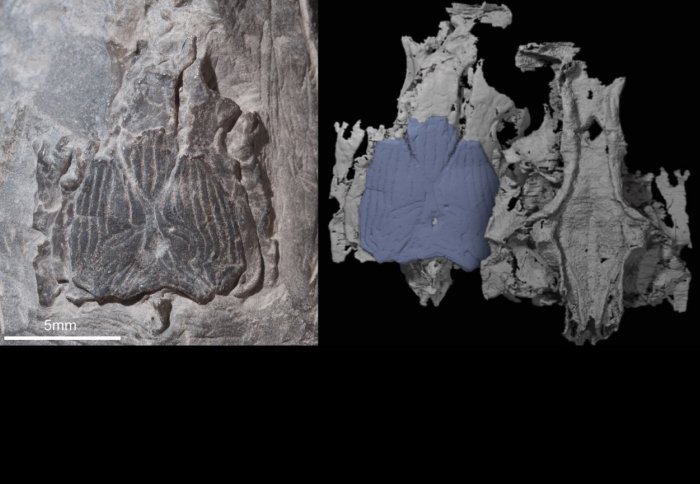

The Janusiscus fossil (left) and a digital rendering based on CT scans (right).

New analysis of a 415 million-year-old fossil has shed doubt on the assumption that sharks are the primitive forerunners of modern jawed vertebrates.

Modern-day sharks have internal skeletons made of cartilage and no bony armour on the outside of their faces, as in other living fishes. It has long been held that sharks are the more primitive form of fish, with bony skeletons evolving later.

In a new study in the journal Nature, researchers from Imperial College London and the University of Oxford suggest that the modern sharks we see today actually shed their bony skeletons early in their evolutionary history.

The fossil - named Janusiscus by the study team - lacks a division across the bottom of its brain case, which places it an early stage of evolution, but it also has a bony external skull. It shares features with two distinct evolutionary branches of early fishes: those with skeletons of cartilage, like sharks, and the bony fishes that also went on to become land vertebrates and, ultimately, humans.

The fossil, first discovered in Siberia in the 1970s, was spotted by Dr Martin Brazeau from Imperial during an internet search for images of a type of bony fish called Dialipina. He immediately saw that the fossil, now held in the Institute of Geology at Tallinn University of Technology in Estonia, could provide some exciting new insights into this period of evolution.

"The Institute had recently digitised their collection, which enabled me to see in high resolution a supposed Dialapina fossil which had previously only been reproduced in a grainy photograph from the early 1990s," says Dr Brazeau, who is from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London. "I could clearly see there was a brain case beneath the bony skull roof - and brain cases can provide a lot of important detail, particularly of features which are specific to certain branches of the evolutionary tree. I knew straight away that this was a fossil that merited further investigation."

The team - involving Dr Matt Friedman and Sam Giles from the University of Oxford - used X-ray micro CT (computerised tomography) scanning to build up a 3D image of the fossil enabling them to 'see' inside the skull and brain case. By comparing the fossil to others from both bony and cartilaginous fishes, the team saw that it had features from both branches of evolution and additional features which are seen in much more primitive fishes. The dual-sided nature of the specimen led them to rename it Janusiscus, after the two-faced Roman god Janus.

"Although Janusiscus does have a bony skull - which led to it being first classified as a bony fish - it lacked many other features you'd expect in that group," says Dr Brazeau. "It also lacked a feature seen in both early bony fishes and sharks, which is a division across the brain case. This clearly places it at an early stage of evolution, before the two branches split. It shows that fish from this time, which are ancestors of both sharks and bony fish, had bones too, and sharks must have lost them at a later point."

Although it's rare to find a surviving brain case from this period, Dr Brazeau dismisses the concept of Janusiscus being a 'missing link' in our understanding of vertebrate evolution.

"It's misleading to think of evolution as a ladder which we reconstruct with 'missing links'," he says. "It's more accurate to think of it as a family tree, and research into evolution is like solving a puzzle. Each new piece you find throws the surrounding pieces into context and helps you to understand them better. Janusiscus has helped us to look at sharks differently and will ensure they are no longer dismissed as being 'frozen' at a primitive stage of evolution."

Reference

'Osteichthyan-like cranial conditions in an Early Devonian stem gnathostome' by S. Giles, M.D. Brazeau and M. Friedman is published in Nature on Monday 12 January 2015. DOI: 10.1038/nature14065

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Laura Gallagher

Communications Division