Scientists reveal the body weight of the world's most complete Stegosaurus

by Colin Smith

Sophie the Stegosaurus

Scientists have discovered that a 150 million year old Stegosaurus stenops specimen would have been similar in weight to a small rhino when it died.

Calculating body mass in animals that have been dead for many millions of years has been difficult for scientists. There are two methods for calculating body mass. One relies on researchers taking measurements of limb bones and extrapolating body mass from a large dataset of living animals, while the other produces a 3D model of the animal and applies densities to body segments to calculate mass. However, both often have varying results.

Although Stegosaurus is something of an iconic dinosaur, scientists know very little about its biology because its fossils are surprisingly rare.

– Dr Susannah Maidment

Junior Research Fellow, Department of Earth Science and Engineering

The researchers from Imperial College London and the Natural History Museum are the first to combine both methods to calculate the body mass of an extinct creature to get an accurate measurement. They used this approach on a Stegosaurus skeleton nicknamed Sophie, which was found in Wyoming in the USA in 2003. They have calculated that the Sophie would have weighed around 1,600 kg, similar in weight to a small rhino.

Dr Susannah Maidment, Junior Research Fellow from the Department of Earth Science and Engineering at Imperial College London, said: “Although the Stegosaurus is something of an iconic dinosaur, scientists know very little about its biology because its fossils are surprisingly rare. We don't actually know whether Sophie was female or male, despite its nickname. When it died, Sophie was a young adult - equivalent to a human teenager. Although there is no evidence for why it died, it seems that the carcass fell into a shallow pond, where it was quickly buried, preventing other animals from scavenging it, and explaining why it is so well preserved.”

Professor Paul Barrett, lead dinosaur researcher at the Natural History Museum said: “These findings identify just how important exceptionally complete specimens like this are for scientific research and collections. Now we know the weight, we can start to find out more about its metabolism, feeding requirements and the growth rates of Stegosaurus. We can also use the same techniques on other complete fossils to find out much more about the wider ecology of dinosaurs.”

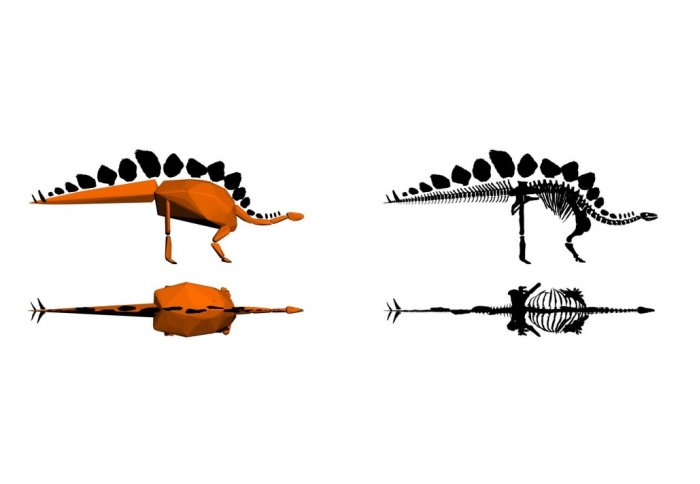

Dr Charlotte Brassey, palaeontologist from the Museum and lead author of the study, added: “Because this incredible specimen is so complete, we have been able to create a 3D digital model of the whole fossil and each of its 360 bones, which we can research in excellent detail without using any of the original bones. We also took the skeleton’s leg bone circumference and compared it to a modern animal of similar size, and came up with matching estimates for the dinosaur’s weight.”

The scientists discovered the body mass of this dinosaur by fitting simple shapes to the digital skeleton and calculating its volume. They then converted this into body mass using data collected from similar modern animals. When compared to figures calculated using the sole method of measuring leg bone circumference in conjunction with the overall weight of various living animals, the results are in close agreement. Both techniques produced an estimate of 1600 kg and, combined, are now considered the most accurate way of measuring the body weight of nearly complete fossil skeletons.

Since the stegosaur arrived at the Museum in December 2013 and before it went on permanent public display one year later, researchers created a 3D model of the skeleton by scanning, photographing and measuring each of its 360 bones. In addition to the findings in this study, the data will underpin a series of future scientific studies, which will uncover more about the unusual lives of Stegosaurus.

The Stegosaurus is now part of the Museum’s collection of 80 million specimens, of which eight million are fossils.

The research is published today in the journal Biology Letters.

*Adapted from press release issued by the Natural History Museum.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Colin Smith

Communications and Public Affairs