Biologists to engineer bacteria for vaccine delivery

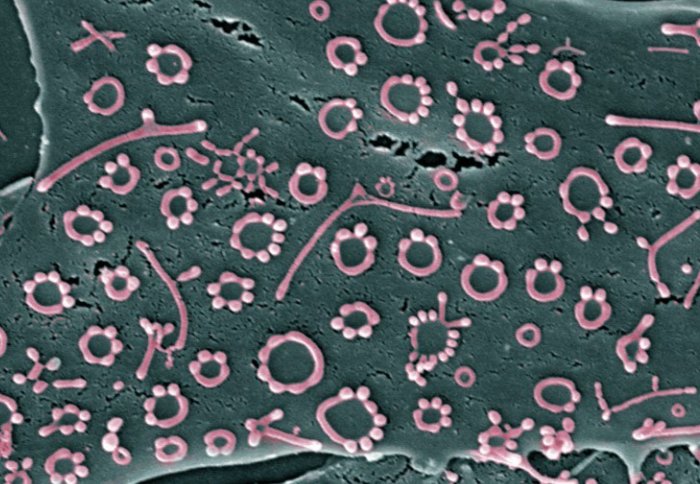

Mycoplasma infection on surface of tissue cultured cells. Image: Kevin Mackenzie/Wellcome Images

An eight million Euro project has been launched with the aim of engineering bacteria to deliver vaccines against antibiotic-resistant infections.

Infections by the Mycosplama group of bacteria cause serious health problems such as pneumonia and infections in livestock cause large financial losses for farmers.

The bacteria are the smallest free-living organisms that lack cell walls, something which makes them resistant to common antibiotics like penicillin. There are currently no vaccines available for humans and pets, or for farm animals apart from pigs and poultry.

This project is important because it’s a real-world application of synthetic biology that has huge potential for tackling a serious health problem in humans and animals.

– Dr Mark Isalan

Now, biologists in the MycoSynVac project propose to engineer the bacteria Mycoplasma pneumonia, removing its ability to cause disease, to create a vaccine ‘chassis’. This would be used to carry selected antigens for fighting different Mycoplasma pathogens. This should create an effective vaccine, using a live but weakened version of the infectious bacteria to prepare the immune system for any potential attacks.

The researchers believe that the vaccine chassis would be adaptable and easier to produce than traditional vaccines for this group of diseases. Two vaccines currently exist for Mycoplasma diseases in pigs and poultry, but they require a complex growth medium, making production slow and prone to errors.

The scientists aim to improve the new Mycoplasma chassis using bioengineering techniques, so that it grows faster in a simpler medium, reducing inefficiency and improving production. Mycoplasma traditionally grows very slowly, but the researchers intend to modify it to reproduce more like faster-growing bacterial species.

Real world applications

Dr Mark Isalan, a reader in gene network engineering from the Department of Life Sciences and Imperial College London, is a partner in the project. He said: “This project is important because it’s a real-world application of synthetic biology that has huge potential for tackling a serious health problem in humans and animals.

"Many projects work on ‘toy systems’ designed to further our understanding of how far we can take biological engineering, but this project has a clear goal. We are applying the lessons we’ve learned in toy systems to the real world.”

“We have been working for a long time to deeply understand Mycoplasma pneumoniae and now, we are ready to take a step forward and use this knowledge for the benefit of society,” adds Maria Lluch, staff scientist at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Spain and scientific co-coordinator of MycoSynVac.

The group hope the chassis technology could also be used to develop other vaccines, as well as be applied in other medical areas, such as therapies for infectious lung diseases.

The international consortium, co-ordinated by scientists at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Spain, includes researchers from Imperial and institutions in France, The Netherlands, Germany, Denmark and Austria. It has received €8 million in funding for five years from the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant under grant agreement No 634942.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division