Scientists reveal first studies of Neptune's constantly changing magnetic field

by Simon Levey

Scientists have made the first detailed simulation of the magnetic field surrounding Neptune, the outermost planet in our solar system.

They combined 26-year old data from Nasa's Voyager 2 probe, with new supercomputer calculations and found a magnetic field that is perpetually changing and rotating on a different axis to the planet.

By studying this model further they hope to improve their understanding of how the Earth's magnetic field controls our space weather. This could help our ability to forecast geomagnetic storms, which can affect communications satellites, computers and other everyday electronics on Earth.

PhD student Lars Mejnertsen, from the Department of Physics at Imperial College London, presented the findings at the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) National Astronomy Meeting in Llandudno, Wales, this week.

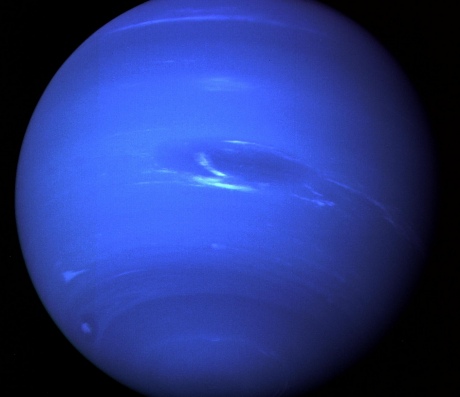

Neptune as observed by Voyager 2 during its flyby in 1989 (NASA/JPL)

When Voyager 2 passed Neptune in 1989 it revealed that the planet's rotation axis is tilted relative to the Sun, its magnetic axis is not at all aligned with its rotation and its magnetic field has a lopsided shape (pictured below).

Lecturer in Planetary Physics, and research team member, Dr Adam Masters said: "Imagine taking the Earth, tipping it over diagonally, and then moving its magnetic north pole to central Europe, and you start to get a sense of what Neptune is like.

"The planet's unique magnetic field is still very poorly understood, and our new modelling represents a big leap forward."

There are no new missions planned to study Neptune so for now, the only way to better understand how the planet works is through computer simulations.

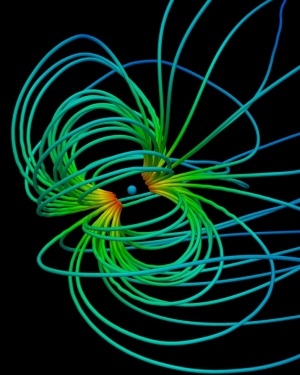

A snapshot of Neptune’s magnetic field from the movie. (Lars Mejnertsen/Imperial College London)

The team, led by Dr Jonathan Eastwood and Professor Jerry Chittenden, investigated the interaction between Neptune's magnetic field and the solar wind - a stream of charged particles, or 'plasma' - emitted by the Sun.

Together they created a simulation that modelled the result of this interaction, an invisible structure called the magnetosphere, using the Science and Technology Facilities Council’s DiRAC supercomputer.

"DiRAC’s ability to use hundreds or even thousands of processors in parallel was crucial to vastly speeding up the calculations," said Professor Chittenden.

"Modelling a whole planet is no easy task. But supercomputers now make it possible and the new simulations explain a lot of what Voyager saw all those years ago," said Dr Masters.

"For example, we can now see how the solar wind enters and circulates around Neptune’s magnetic field. The combination of the dramatic planetary rotation and this circulation pattern is why Voyager 2 found a ‘lopsided’ magnetosphere."

Understanding Neptune better will also help astronomers understand planets outside the solar system. A large number of those found to date are around the size of Neptune, so studying this planet should give an insight into conditions on those other distant worlds.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Simon Levey

Communications Division