Crocodile attack data highlights how to avoid getting killed

by Simon Levey

A new set of interactive infographics created from long-term data about attacks highlights the best ways to avoid being bitten by a crocodile.

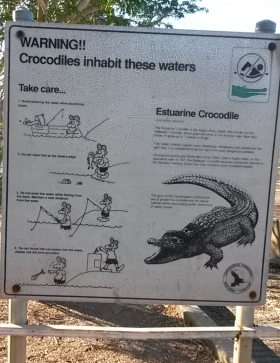

The infographics, now available on a website called CrocBITE, are accompanied by a new booklet providing advice on how to avoid getting killed, including tips on how to behave in and around the water, and what to do if you are bitten.

The booklet has been designed by Dr Simon Pooley to appeal to local people, conservation managers and visitors to the places where these giant reptiles are most commonly found. It will be distributed for free in southern Africa later this year.

Dr Pooley, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, analysed historical information about crocodile attacks in southern Africa during the last 65 years, turning the numbers into clear graphics that are easily accessible.

They reveal what kinds of people have been attacked, what people were doing just before they were attacked, and details about where different kinds of attacks took place. For example, in South Africa and Swaziland:

- Victims of attacks have mostly been boys

- Most men have been attacked while fishing, while most women were attacked whilst doing domestic chores or crossing water

- Most girls have been attacked while swimming or doing domestic chores, while most boys were attacked whilst swimming

- Since the year 2000, there has been an increase in attacks in man-made water bodies such as dams and reservoirs

Accurate information on who is being attacked, when, while doing what, and where, will enable targeted measures to protect people and crocodiles, including more focused education.

– Dr Simon Pooley

Department of Life Sciences

Dr Pooley's analysis of the environmental data so far shows that crocodile attacks are most likely in the summer months between October and March, and within this period, at times when daily minimum temperatures are higher than average.

Like all reptiles crocodiles are ectothermic; relying on the warmth of the sun and their surroundings to generate enough energy to hunt. They are less active and feed less during cooler times of the year, which may partly explain this correlation between attack incidence and temperature.

"More data are needed about the activities of crocodiles - as well as those of the humans they come into contact with - before we can draw firm conclusions," Pooley said.

In a recent paper in the wildlife conservation journal Oryx, Dr Pooley explores the advantages and limitations of collecting data about the environmental conditions when crocodile attacks happen.

He said, "In particular, information about rainfall, temperature and water levels can help us test competing hypotheses on why crocodile attacks are seasonal.”

REPORT AN ATTACK

Dr Pooley's research gathered information from newspapers, interviews and other official documents, but these figures do not tell the whole story as not all attacks are reported, and reports may be unreliable and lack key facts.

Members of the public, tourists and wildlife experts are invited to submit detailed information about crocodile attacks, wherever they occur in the world, via the website to help build up a better picture about the relationships between humans and crocodiles.

Members of the public, tourists and wildlife experts are invited to submit detailed information about crocodile attacks, wherever they occur in the world, via the website to help build up a better picture about the relationships between humans and crocodiles.

Dr Pooley said: "While crocodile attacks will never be a priority at national or even regional levels, attacks are devastating for the families and communities of victims, and may prove lethal for the crocodile (or crocodiles) in the area, because they are often killed following an attack.

"Accurate information on who is being attacked, when, while doing what, and where, will enable targeted measures to protect people and crocodiles, including more focused education."

The CrocBITE website was created by Dr Adam Britton, from the Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, and maintained by Brandon Sideleau, with a grant from Charles Darwin University in Australia. CrocBITE includes a fully searchable database of nearly 3,000 incidents worldwide, together with general information on attacks and how to avoid them. Drs Pooley and Britton are collaborating on extending the visualisation component of the website to all the regions covered by CrocBITE.

The project was funded by an Imperial College London / ESRC Impact Acceleration Award grant to Dr Pooley, who worked with data design specialists Information is Beautiful Studio in London, and schools and conservation managers in Swaziland and South Africa.

Email croc.conservation@gmail.com to request a booklet, or for more information.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Simon Levey

Communications Division