HS2 and Crossrail: Scientists predict the economic effect of major rail projects

by Simon Levey

HS2's London to Birmingham railway may create just over half of the total economic gains predicted by the UK Government.

A new mathematical model suggests that major rail infrastructure projects, such as High Speed 2 (HS2) and London Crossrail, will cause some businesses and homeowners to lose out financially, when other destinations become better connected.

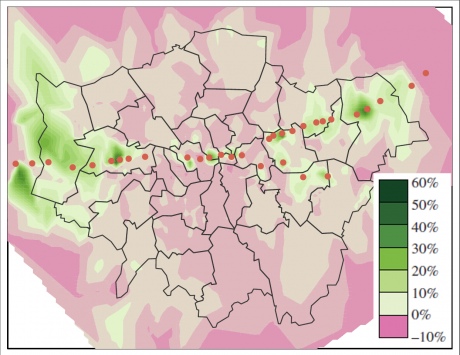

Its creators, from Imperial College London, have produced a map that shows which areas of London will be most affected in this way by the construction of Crossrail across the city.

Map showing percentage change in local connectivity due to Crossrail

"Large scale transport projects are big political, economic and social undertakings, but often the effects on their most immediate neighbours make the biggest headlines," explained Dr Aaron Sim, one of the study authors from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London.

"However, business owners with poor access to the transport infrastructure will find that previously distant competitors suddenly become much more attractive, and their customers may choose to go elsewhere."

The study is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

HIGH SPEED 2

The scientists applied their model to analyse the effect of the proposed High Speed 2 (HS2) 'phase one' Birmingham to London route.

When I'm looking for a launderette to have my shirts cleaned, I wouldn't travel much beyond the high street, so businesses like this probably won't see much benefit, if any, from HS2

– Dr Aaron Sim

Study author, Department of Life Sciences

HS2 has been estimated by a KPMG report, commissioned by the Department for Transport in 2013, to create £15 billion annually in increased economic output, with phase one estimated to deliver 40 per cent of this benefit (£6 billion per annum).

However, the new study predicted that phase one would create only £3.6 billion annually in increased economic output; less than one per cent of current output of both cities.

The scientists calculated overall, long-term benefits by taking into consideration not just the positive but also the negative impact on businesses in London and Birmingham.

The psychological process known as time-budgeting explains how people are prepared to invest a certain amount of time travelling to achieve a certain task, and different amounts of time for different types of activities.

"When I'm looking for a launderette to have my shirts cleaned, I wouldn't travel much beyond the high street, so businesses like this probably won't see much benefit, if any, from HS2," said Dr Sim.

"On the other end of the travelling-time budget scale, when I'm looking for highly specialised financial services, say, I would be willing to travel for as long as it takes to meet the right company," he said. “In this particular context, HS2 will be of little benefit as far as building new connections across cities is concerned as the passengers are already willing to endure a longer journey time."

CROSSRAIL

Crossrail is currently under construction beneath London, where it will run between Reading in the West and Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the East, via The West End and Canary Wharf (pictured above). It is projected by local government to bring up to £1.24 billion per year of economic advantages by 2026.

I would be more inclined to go [to Canary Wharf] where there are a mass of specialist firms. That will have a knock-on effect on businesses providing similar services elsewhere

– Dr Aaron Sim

Study author

The researchers say these benefits will not be shared by the whole city. Large areas of London will suffer a slight drop in connectivity not just relative to those along the route but also to their current levels, and therefore feel a negative effect on business.

"Right now I might travel an hour to get to a meeting somewhere in London," said Dr Sim. "But if Crossrail gets me to the heart of London's financial district in Canary Wharf in 25 minutes, I would be more inclined to go there where there are a mass of specialist firms. That will have a knock-on effect on businesses providing similar services elsewhere."

Dr Sim carried out the study with Professor Michael Stumpf, also from the Department of Life Sciences, Professor Mauricio Barahona, from the Department of Mathematics, and Professor Sophia Yaliraki, from the Department of Chemistry at Imperial.

They say the findings should be used to help politicians and civic planers to put in place the most efficient, widely beneficial and fairest infrastructure. They also say that it would give the chance for business owners to prepare for changes to come.

The scientists derived their results using the mathematics of networks and existing models of human mobility from physics, which are used to model many things that rely on human interaction, such as disease transmission.

They assessed the rail projects by looking at how many new social ties it was possible for people to make in different city regions - based on how easily they can reach one another via cars, rail, walking and cycling networks - and used this to predict the economic productivity in GDP (Gross Domestic Product).

To test the model, they applied it to 102 major cities in the United States of America and found that it predicted the GDP of those regions with a high degree of accuracy.

The authors plan to further test and validate the model on new global cities that are undergoing rapid growth in both population and infrastructure.

"In these cases, the challenge is obtaining the data, which for many developing countries may not be openly available or complete", said Dr Sim.

Journal Reference

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Simon Levey

Communications Division