Dr Martyn Sené from the National Physical Laboratory visits the TSM CDT

by Lucy Stagg

On Wednesday the 15th of November we were delighted to host Dr Martyn Sené at the TSM CDT. Marc Coury (cohort 3) writes:

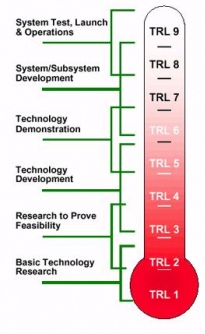

Dr Sené is the Deputy Director and Operations Director at National Physical Laboratory. He introduced us to what the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) does and gave us a summary of his experience of the cold fusion controversy. When describing the role of NPL Martyn cited many interesting examples. One key role is that of standardising measurements, a need stated in The Magna Carta, 1215 (ratified by Parliament in 1225): "There shall be but one Measure throughout the Realm" "One measure of Wine shall be through our Realm, and one measure of Ale, and one measure of Corn, that is to say, the Quarter of London; and one breadth of dyed Cloth, Russets, and Haberjects, that is to say, two Yards within the lists. (2) and it shall be of Weights as it is of Measures." (reproduced from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weights_and_Measures_Act) Martyn also told us of his experience of cold fusion. He was working at Harwell Laboratory when Pons and Fleischmann gave their press announcement of cold Fusion in March 1989. Soon after, he was in a team tasked with reproducing these results at Harwell. During the summer of 1989, they tried many variants of Pons and Fleischmann’s electrolysis cell; but to no avail. At the same time, more press conferences were held to announce positive results - although many were later retracted due to the discovery of various mistakes and errors. It was a big deal. If cold fusion would have been a very important discovery, as it would have solved many of the world's problems: oil dependency, global warming, radioactive waste from nuclear fission powerplants, strip mining for coal, acid rain. There was a lot of pressure, from the media, politicians and fellow scientists. Martyn and his team published their negative results in the paper "Upper bounds on 'cold fusion' in electrolytic cells" in Nature in November 1989, which marked the beginning of the end of the cold fusion debate. Martyn noted some of the lessons learned from his experience with cold fusion, and the importance of trying to maintain scientific objectivity in the face of external pressures such as the media, politics and commerce. Martyn's career has spanned the whole range of “technology readiness levels” . Starting out in academia he worked on basic technology research. His move to the Harwell Laboratory, and subsequently to AEA Technologies, enabled him to experience the processes by which basic research is taken up the technology readiness ladder, all the way to a viable working new technology. In his current role at NPL, he sits in the middle of the technology readiness ladder, between government, academia and business.

Martyn's career has spanned the whole range of “technology readiness levels” . Starting out in academia he worked on basic technology research. His move to the Harwell Laboratory, and subsequently to AEA Technologies, enabled him to experience the processes by which basic research is taken up the technology readiness ladder, all the way to a viable working new technology. In his current role at NPL, he sits in the middle of the technology readiness ladder, between government, academia and business.

Interesting recent problems that NPL has been involved in include: the temperature of explosions; the ripeness of strawberries; the quality of biscuits (based upon the sound they make when broken); and training of sniffer bees for airport security.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Lucy Stagg

Faculty of Natural Sciences