All-female animals adapt without sex by stealing foreign DNA

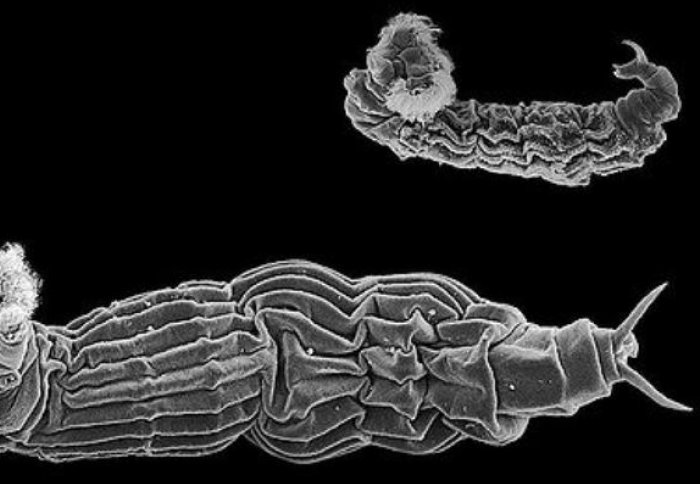

Two bdelloid species

A group of female-only animals that reproduce by cloning have adapted to different environments by taking up DNA from other organisms.

Most animals reproduce sexually, and the mix of genes from both parents helps each generation to take on new characteristics. If these characteristics are favorable to the environment, then over time they will spread through the whole population. However, one microscopic animal group hasn’t had sex for at least 50 million years.

Most people are unaware of their existence, yet every time you step on soil or clear moss from a pavement, you come into close proximity to these strange and fascinating animals.

– Professor Tim Barraclough

Bdelloid rotifers are a group of microscopic animals that live in wet habitats such as ponds, streams and soil, and on mosses and lichens. Less than half a millimetre long, these animals produce offspring that are genetic clones of their mothers, and males have never been found. Bdelloids have been around for over 50 million years, apparently without sexually reproducing.

It has long been a mystery how these creatures adapted to changing conditions and diversified into a large number of species without the benefits of sexual reproduction. Previous work found that bdelloids had taken up DNA from other organisms – known as horizontal gene transfer – and speculated that this might in some way have compensated for the lack of sex.

Adapt and survive

A new study, led by Imperial scientists, has revealed that bdelloid rotifers are still taking up significant amounts of new DNA to help them adapt to their environments, and that this is how they continue to evolve and diversify. The study found that different bdelloid rotifer species have taken up DNA from a wide variety of organisms, including fungi and bacteria, as they adapted to specific environments.

The study, published this month in BMC Biology, shows that sexual reproduction is not the only way to introduce the variation needed for species to adapt to different conditions.

The team looked for the genetic basis of differences among species by sequencing genetic information from four closely related species of bdelloids in different habitats.

They found that bdelloid species have taken up thousands of genes from plants, bacteria, fungi, and single-celled organisms.

Bdelloid rotifers under the microscope.

Most of these genes were acquired by the common ancestor of all bdelloids, and so are present in all modern species, but a substantial number are only present in only one species. Lead author and former PhD student in the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial Isobel Eyres explains: “Our results show that foreign DNA has contributed to genetic divergence among species of bdelloids.

“For example, one of our species lives on moss whereas the others live in ponds. The moss species has acquired a different set of foreign genes, potentially helping it to meet the different challenges of living there. The genes code for proteins involved in breaking down food and surviving stressful conditions such as desiccation (drying out).”

“We estimate that one foreign gene has been incorporated into each species every 78,000 years, on average’” adds co-author Professor Tim Barraclough from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial.

“Although this rate is probably too low to compensate for the costs of asexuality in full, it is likely that bdelloids also take up DNA from each other or from other animals by the same mechanism. This is harder to detect but is something we are hoping to pin down in our future work”.

Repair and upgrade

Exactly how bdelloids take up DNA remains uncertain. One idea is that it happens by mistake when bdelloid chromosomes are repaired following damage caused by desiccation. The ability to recover from complete desiccation is another special feature of bdelloid biology.

However, the present study found that foreign genes have also been taken up in bdelloids that cannot survive desiccation and live in permanently aquatic habitats (such as ponds), albeit at a slower rate. This means that desiccation cannot be the only mechanism for DNA uptake in bdelloids.

Professor Barraclough adds: “Bdelloid rotifers are a remarkable group of animals that challenge our understanding of evolutionary processes. Most people are unaware of their existence, yet every time you step on soil or clear moss from a pavement, you come into close proximity to these strange and fascinating animals.”

-

‘Horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers is ancient, ongoing and more frequent in species from desiccating habitats’ by Isobel Eyres, Chiara Boschetti, Alastair Crisp, Thomas P. Smith, Diego Fontaneto, Alan Tunnacliffe and Timothy G. Barraclough is published in BMC Biology.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division