Saturn's magnetic bubble explosions help release gas

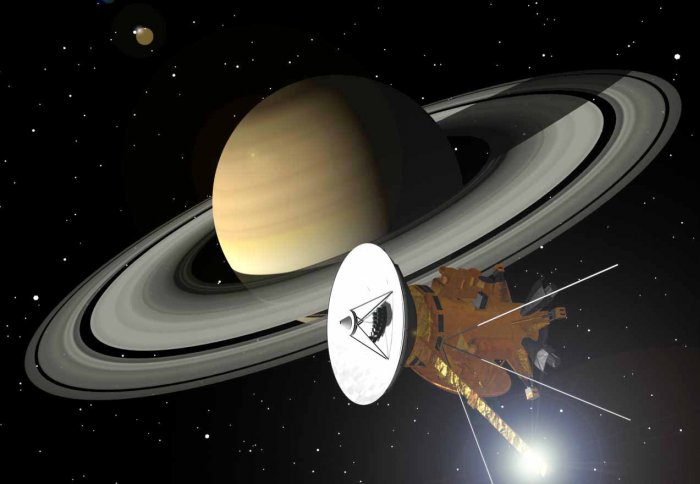

Scientists have found the first direct evidence for explosive releases of energy in Saturn's magnetic bubble using data from the Cassini spacecraft.

Saturn creates its own magnetic bubble, known as its magnetosphere, which protects it from the solar wind. Magnetic reconnection is an explosive process in the magnetosphere that allows material such as gas and plasma (the fourth state of matter) from the solar wind to get in, and material from inside to get out.

Understanding reconnection in such extreme environments as Saturn’s magnetosphere gives us a better understanding of how these systems behave.

– Dr Jonathan Eastwood

A group of researchers led by Lancaster University and including physicists from Imperial College London used data to show that Cassini had passed through the region at Saturn where magnetic reconnection was occurring, something that has never been directly observed before.

Cassini, a joint mission between NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency, has been exploring Saturn for 11 years. These latest finding are reported today in the journal Nature Physics.

Dr Jonathan Eastwood, from the Department of Physics at Imperial and a co-author of the paper, studies the Earth’s magnetosphere, where reconnection occurs, albeit on a much smaller scale.

“Magnetic reconnection is important for understanding space weather, such as the physics of geomagnetic storms caused by the solar wind,” he said. “Understanding reconnection in such extreme environments as Saturn’s magnetosphere gives us a better understanding of how these systems behave.”

Moon emissions

One of the mysteries this gives us clues to answering is how Saturn’s magnetosphere gets rid of gas from Saturn’s tiny icy moon Enceladus. Through jets at its south pole, this tiny 500 km-sized moon ejects around 100 kg of water into space every second.

Dr Chris Arridge from Lancaster, lead author of the study, said: “Water from the Enceladus plume is trapped in Saturn’s magnetosphere. We know it can’t just stay there for ever and until now we have not been able to work out how it has been ejected from the magnetosphere.”

Previously, magnetic reconnection at Saturn was thought to not be large enough to allow enough plasma to escape from the magnetosphere to expel Enceladus’ gas. The new results show that Saturn’s magnetic reconnection lasts longer and is more continuous than predicted, allowing sufficient plasma to escape.

Onwards to jupiter

“Observing the physics of Saturn’s magnetosphere will also allow us to better test and understand the dynamics of other large magnetic environments, such as Jupiter,” Dr Eastwood added.

Jupiter will be visited by the upcoming JUICE mission, launching in 2022, which will carry instruments designed and built by an Imperial team led by Professor Michele Dougherty.

-

'Cassini in situ observations of long-duration magnetic reconnection in Saturn’s magnetotail' by C. S. Arridge, J. P. Eastwood, C. M. Jackman, G.-K. Poh, J. A. Slavin, M. F. Thomsen, N. André, X. Jia, A. Kidder, L. Lamy, A. Radioti, D. B. Reisenfeld, N. Sergis, M. Volwerk, A. P. Walsh, P. Zarka, A. J. Coates & M. K. Dougherty is published in Nature Pysics.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division