Lung cells that battle a cold virus identified by scientists

by Kate Wighton

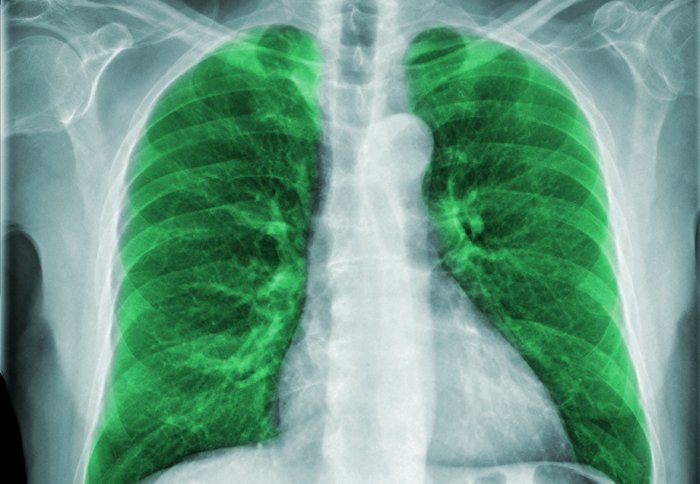

Scientists have identified a type of immune cell in the lungs of humans that may help fight respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The virus is one of the main causes of childhood hospitalisation, severe lung infection in the elderly, and the common cold.

The findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, suggest nose sprays could be the most efficient way of delivering a vaccine against the virus.

We are mainly concerned about how dangerous this virus can be to the young and old

– Dr Christopher Chiu

Study author

The researchers found that a type of immune cell, called a resident memory T cell, is particularly active during RSV infection. These immune cells help to identify invaders, raising the alarm to the rest of the body and killing infected cells.

Although scientists already knew these cells help fight influenza infections in mice, this is the first time they have been shown to help protect against RSV in humans. The team also found that individuals with naturally higher numbers of these cells were less likely to suffer symptoms.

Dr Christopher Chiu, the lead author of the research from the National Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial, says the work suggests current vaccine efforts should be directed toward nose sprays.

“There are around 50 potential vaccines being investigated at the moment, and a few of these will be delivered in nasal sprays. Our work suggests a nasal vaccine will be more likely to reach these immune cells, which are in the lungs, than injecting a vaccine into the arm. The hope is that within the next five years there will be a vaccine licensed for use to reduce the massive toll of this infection.”

RSV is transmitted through coughs and sneezes and may be responsible for up to 10 per cent of winter GP visits from elderly patients. It also infects every child before the age of two.

“The virus infects the airways and lungs, and in healthy people can cause a heavy cold - the type that keeps you off work for a couple of days. However, we are mainly concerned about how dangerous it can be to the young and old, where it can cause lung infections such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia.

“We’ve only had technology available over the last ten years to widely and accurately diagnose the virus, and so didn’t realise the full extent of its prevalence.

"We now know it’s the most common cause of hospitalisation of babies – resulting in up to 200,000 baby deaths worldwide every year. And in the older population it’s almost as dangerous as flu. So far this year flu cases have been relatively few, but there have already been lots of hospital admissions with RSV.”

Studies suggest the body’s natural defences against the virus are pretty weak, adds Dr Chiu. His team wanted to identify the immune cells involved in this defence, to explore whether the cell’s powers can be boosted.

In their study the team infected 49 healthy volunteers with RSV in closely monitored conditions. They kept the participants in hospital for 10 days – studying them before and after infection.

Just over half developed an infection – with most of the infected group developing symptoms of a common cold. The team took small tissue samples from the airways of the volunteers who developed an infection, and analysed the immune cells.

"RSV-specific airway resident memory CD8+ T cells and differential disease severity after experimental human infection" is published in Nature Communications</

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Kate Wighton

Communications Division