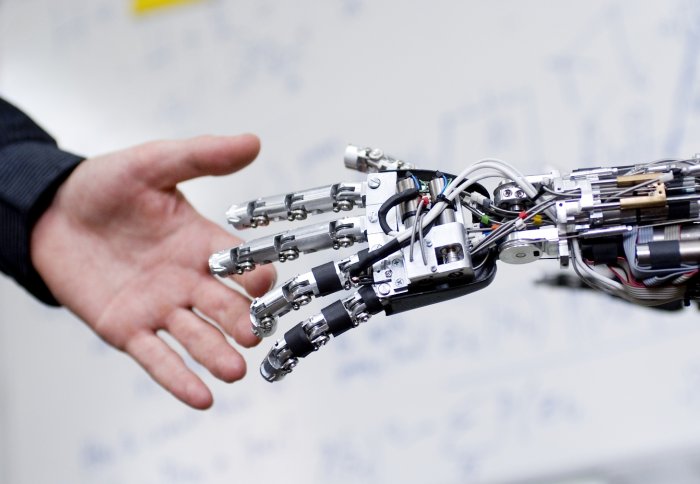

Artificial intelligence: a force for good or evil?

Artificial intelligence (AI) expert Professor Murray Shanahan has been speaking to Nancy Mendoza about a new centre that looks at the future of AI.

AI is created when computers are programmed to, to a greater or lesser extent, think for themselves. Examples run the gamut of existing technologies, such as driverless cars, through to the idea of creating a human level intelligence, which at present can only be dreamed of.

The Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence has been set up to explore the opportunities and challenges of AI, a potentially epoch-making technological development, and how it might impact humanity.

Professor Murray Shanahan

The Centre is a collaboration led by the University of Cambridge with links to Imperial College London, the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford, and the University of California, Berkeley. Professor Shanahan, who is from the Department of Computing, is leading Imperial’s involvement with the Centre.

What will the Leverhulme Centre do?

There are both short and long term implications of AI that need to be considered from all angles. The Centre brings together computer scientists, philosophers, social scientists and others to examine the technical, practical and philosophical questions artificial intelligence raises for humanity in the coming century.

The Centre is all about the future of AI, what are your aspirations for the field?

Having children really makes you think, it makes the future very real. AI will play a very important role in the lives of my children’s generation, and hopefully will change the world for the better.

I’m very excited by the prospect of building ever more sophisticated AI – I’m just as excited about that as I was as a kid, reading Asimov and thinking about Hal, the AI computer in “2001, A Space Odyssey” – but I’m also pulled in a another direction, which means I’m compelled to look at what AI might mean from a social and a philosophical point of view.

What is your role in the Centre?

For the past 10 years I’ve worked mainly on understanding how brains work. I develop computer code that mimics some of the networks of the human brain. More recently, the larger social and philosophical questions around AI are also taking up some of my day job. Thanks to the Leverhulme Centre, I’ll be able to split my time more evenly between working on AI technology and considering the context and possible side effects of current and future developments.

Because I actually build the code that will support some of the future developments, I’m able to act as a translator between the technical and the social and philosophical aspects of AI research within the Centre.

When you talk about long term implications, will the Centre be trying to prevent scenarios we see in science fiction like “I, Robot” or “Ex Machina”?

Sort of. To be honest it isn’t really appropriate to look at science fiction for the long term implications of AI. In science fiction there is a tendency to anthropomorphise AI – to treat it as if it were equivalent to a human – and make it evil. This makes a good story but it doesn’t help us to think through what the technology we build might actually be like.

Even a very smart AI isn’t necessarily going to be human-like. Rather, it will follow an instruction that we give it, which might be to achieve a particular goal. Because it is intelligent, it can look at achieving its goal in all sorts of ways and there might be unforeseen side effects of that.

Nick Bostrom, from the University of Oxford, is involved with the Centre, too. He came up with an interesting thought experiment called “The Paperclip Maximiser”, where an AI entity is told to make paperclips but it has to work out how best to do it. Eventually it becomes so good at making paperclips that all Earth’s resources, and eventually outer space too, are given over to paperclip making. This sort of thought experiment is usually more useful than looking at science fiction.

So, you’re no longer a fan of science fiction, then?

Still from Ex Machina

Actually, I still love science fiction. I recently consulted on the script development for the feature film, “Ex Machina”. The writer-director, Alex Garland, read my book about consciousness early in the script-writing process, and later on he emailed me. He wanted me to read his latest draft, which was excellent, and then we met a few times so he could chat about AI and consciousness. He wanted to know if the script rang true in terms of what AI researchers might do, how they might talk, and that sort of thing. In the final film there was even a hidden reference to a book I wrote, in the form of some Python code that one of the characters is editing – if you run the code, it outputs the ISBN number for my book!

I believe Science Fiction has a really important role in the social critique of new technology and in raising important philosophical questions.

The story of “Ex Machina” has echoes of the Prometheus myth, from ancient Greek mythology. This is a popular trope in Science Fiction of the 20th and 21st centuries – the idea that introducing a paradigm changing technology could be the downfall of the scientist, for example Frankenstein, goes right back to Prometheus stealing fire from the gods to give it to human beings. The exploration of this theme in art encourages us to think through the consequences of AI, but we do sometimes have to be careful to separate out the philosophical value of the story from its entertainment value.

What about the short-term implications of AI?

Google's driverless car prototype

When we talk about the short-term, we’re thinking about the implications for technology we already have. A good example is the self-driving car (image via Commons); the technology is already in place and it’s not far from being available to consumers. Even if cars are not, in the near-term, fully self-driving, we’re certainly going to witness increasing autonomy of cars over the next few years.

So, as well as engineering challenges, there are employment implications – autonomous vehicles might take over from truck drivers, for example. There will also be legal issues: where does responsibility lie when an autonomous vehicle is involved in an accident? It would be difficult to blame the car, in a legal sense, so is it the owner, the manufacturer, the local highway authority, or someone else who is responsible?

On the flip side, there are social benefits from autonomous cars. Primarily, we would expect a reduction in serious accidents. Humans are very bad at driving, our attention and concentration is poor, and we tend to fall asleep, but a self-driving car that is programmed to never hit anything, has the potential to be far safer.

There are environmental advantages too. Where human drivers use extra fuel through poor driving style the driverless car will know the optimum style for fuel efficiency.

The Centre will look at this kind of technology and think through examples – it’s not just about driverless cars, there are scarier examples, such as autonomous weapons, as well as those with clearly benevolent applications, such as artificial intelligence in the monitoring of patients in care.

What short-term problems will Imperial address?

One aspect of Imperial’s involvement in the Centre is around the transparency of decision making in intelligent machines.

It’s very important to know how a machine got to the decision it got to – you don’t really want to rely just on the outcome of the decision e.g. choosing treatment A or treatment B for a patient, or even who to arrest for a particular crime.

Intelligent machines make errors sometimes, too. For example, image understanding programs have been written that are able to recognise big cats, and can even learn to distinguish between a jaguar, a leopard, and a cheetah. When shown a sofa with a jaguar print cover, one program incorrectly identified it as a jaguar (Image via Commons.).

Intelligent machines make errors sometimes, too. For example, image understanding programs have been written that are able to recognise big cats, and can even learn to distinguish between a jaguar, a leopard, and a cheetah. When shown a sofa with a jaguar print cover, one program incorrectly identified it as a jaguar (Image via Commons.).

To enable human intervention and supervision, you can engineer the underlying techniques so that the decision making process is easier to interrogate. Alternatively, you can reverse engineer on top of existing programming, to, for example, make it possible to visualise a series of choices that the machine was presented with.

And how about Imperial’s role in addressing long term problems?

Suppose we do create a very powerful technology, which leaves us with more leisure time and overall greater abundance; what do we want that world to look like? What is a meaningful life in a post-work society?

Also, one of the Imperial projects looks at what the philosopher Aaron Sloman called “the space of possible minds”. Human minds are only one example of the kinds of minds on earth. Suppose we do create human level cognition in AI, does that widen the “space of possible minds” to include AI alongside humans and animals? What might be the implications of that for rights or personhood of AI?

Western Scrub Jay - a highly intelligent member of the crow family

We’re working with Nicky Clayton and Lucy Cheke at the University of Cambridge on this. They are both interested in comparative cognition, working with highly intelligent animals, such as birds from the crow family (Image via Commons).

How likely is it really that we will create human level cognition in AI?

Right now it’s easy to mock this because even the most sophisticated AI robot no more has a mind than your toaster does! It has no awareness of the world around it, not in any meaningful way. A robot vacuum cleaner might have a slight hint of that – it can react to its environment as it moves around, avoiding obstacles – but it’s not actually thinking individually and it doesn’t have consciousness.

At the moment we don’t know if or how human level intelligence will be incorporated into AI, but we would be being reckless not to consider it as a possible outcome of today’s research.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Nancy W Mendoza

Communications and Public Affairs