'Holy grail' bacteria for crop farming debunked by scientists

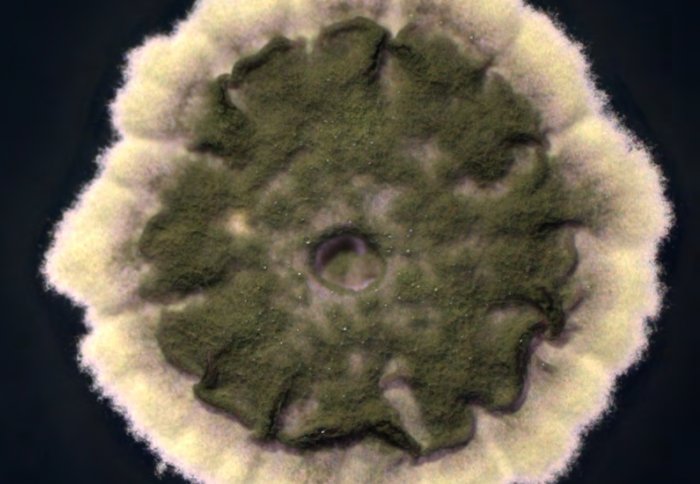

Streptomyces thermoautotrophicus

The proposed ability of a bacteria strain, which could have supplied nitrogen to crops without artificial fertilisers, has now been disproven.

Crops depend on a supply of nitrogen for their growth. Farmers can supply it in the form of fertilisers but it can also be produced by certain bacteria living in the soil.

It’s disappointing, but it’s not surprising.

– Dr James Murray

These bacteria are able to extract nitrogen from the air because they contain special enzymes called nitrogenases. But this process, called ‘fixation’, is always limited by the fact that oxygen also present in the air is poisonous to the enzyme.

Bacteria that live in nodules surrounding the roots of leguminous plants, such as beans and peas, gain protection from oxygen from the plant and in turn supply it with nitrogen. However, many important crop plants such as rice and wheat cannot form partnerships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria and rely on scant nitrogen in the soil or on artificial fertilisers.

Manufacturing nitrogen fertilisers requires enormous amounts of energy and applied fertilisers can cause ecological damage if they wash off of farmland into river and lakes.

amazing discovery

In the 1990s, a German team reported that they had found a bacteria that used a nitrogenase that could operate in the presence of oxygen. If the workings of this enzyme could be unravelled, then the ability to fix nitrogen could be engineered into crop plants, allowing them to harvest their own nitrogen and reduce the need for artificial fertilisers.

Example charcoal fire in Germany. Image: James Murray

The bacteria, Streptomyces thermoautotrophicus UBT1, was found in a unique environment - the soil covering a burning charcoal fire. It was labelled a ‘holy grail’ for plant biotechnology projects hoping to engineer plants to fix their own nitrogen. No other samples of the bacteria had been found however, until several international teams went on the hunt, including a team from Imperial College London.

The teams found two similar strains of bacteria from a coal seam fire in the United States and a charcoal fire in Germany. They were also able to obtain of some of the original bacteria. The teams joined up to investigate the nitrogenases of their bacteria and see if they were able to fix nitrogen in the presence of oxygen.

Their results, published today in Scientific Reports, show none of the three strains of S. thermoautotrophicus are able to fix nitrogen at all.

Too good to be true

Dr James Murray, a co-author of the study from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial said: “When it was first reported that there was a bacteria that could fix nitrogen in the presence of oxygen, it seemed too good to be true, and it turns out it was. It’s disappointing, but it’s not surprising.” Dr Murray suggests the original study may have had problems with contamination, among other issues.

The new research included teams from Harvard Medical School, Michigan State University, National University of Rosario, Argentina and Aachen University, Germany as well as TheLab Inc from California, which re-isolated the original bacterial strain.

While the existence and oxygen-tolerant properties of this particular nitrogenase have been disproven, and Dr Murray believes they are unlikely to exist, the team at Imperial are investigating other ways in which nitrogenases may be protected from oxygen.

The hunt for new ways to supply important crop plants with natural nitrogen also continues in other projects at Imperial. In December 2015, £4.5 million of new funding was awarded to researchers from the Department of Life Sciences to engineer bacteria to release extra nitrogen that could be used by crops.

-

'Streptomyces thermoautotrophicusdoes not fix nitrogen' by Drew MacKellar, et al is published in Scientific Reports.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division