From cancer and heart disease to Zika virus - unlocking secrets of the placenta

by Kate Wighton

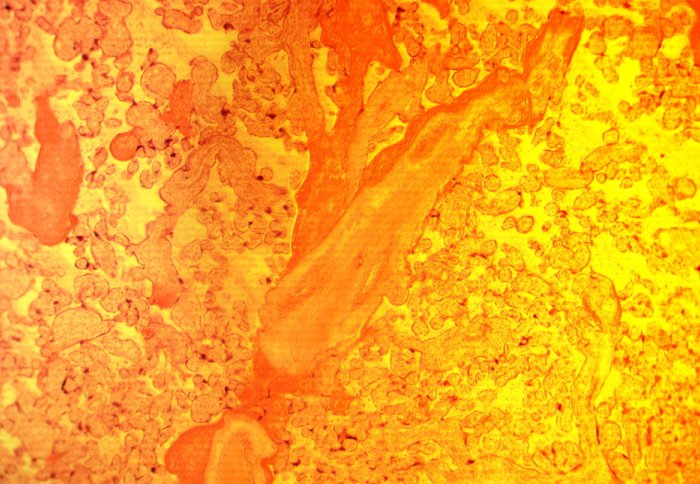

Human placenta

Placenta is a medical marvel. A half kilo mass of blood vessels and connective tissue, it's the only organ the body grows from scratch in adulthood.

Scientists are now realising that this temporary organ is not only essential for a healthy pregnancy, but it may even determine a baby's future health.

Yet, despite being so crucial to life, we still know relatively little about this amazing organ, says Dr Beth Holder, from the Department of Medicine at Imperial.

"The placenta is the interface between the mother and baby – and is how the baby receives oxygen and nutrients from the mother. However, it is hugely unstudied compared to other organs in the human body – and at the moment there are many more questions than there are answers. Answering these questions is vital for helping us reach a point where every pregnancy results in a healthy baby. "

This month Dr Holder was awarded a prestigious SET for Britain prize for her placenta research, in a ceremony at the House of Commons in London.

Here she reveals the fascinating world of the placenta.

How to recycle your placenta

The placenta is a lifeline to the fetus – and abnormalities can result in problems in pregnancy and fetal development. However studying the placenta can provide insights into diseases and conditions beyond pregnancy, explains Dr Holder.

“Because the placenta is the only temporary organ our bodies are able to grow, it has implications for many areas such as cancer and heart disease. For instance, placenta development involves growing new blood vessels – which is process also seen in tumour growth. And the study of how placental blood vessels function, can have applications to cardiac research.”

The placenta may even give insights into organ transplantation and autoimmunity, says Dr Holder.

“The placenta is made up of fetal cells – which contain DNA from both the mother and father. Yet the mother’s immune system doesn’t reject it as a foreign organ, as she would if she received a donated organ from the father.

This phenomenon has fascinated scientists for decades. Understanding what is happening to the mother’s immune system during pregnancy might help us explain why the immune system attacks organs in other situations, such as transplantation, or autoimmune diseases including diabetes ”

Dr Beth Holder

Dr Holder adds that one of the advantages of placental research is there is no shortage of raw material.

"After a woman has given birth, the organ is usually thrown away – it may seem odd to many people that the body goes to the trouble of making a whole organ, only for us just to thrown it in the bin. We approach women and ask if they would consider donating it to research, and they are usually very happy to do so."

She continues: "This becomes even more important when the mother may have experienced a complication of their pregnancy, such as pre-eclampsia or premature birth. By donating their placentas in these often very stressful situations, these mums are really doing something really wonderful to help us understand these diseases, and hopefully develop diagnostic tests or treatments to help prevent this happening in the future”

Dr Holder adds that a number of hospitals and universities around the UK collect placentas for potentially life-saving medical research.

And she is sceptical about the emerging trend of parents eating the placenta - by cooking it, making it into a smoothie, or free-drying it and adding into a pill.

“We do occasionally hear about women who plan to eat their placenta, either by making a smoothie, or having pills made. I can’t say that there is any scientific evidence that this is harmful, but there is certainly no evidence that it is beneficial either. There is the worry that some companies may be preying on pregnant women to sell something that could be completely pointless.”

The placenta's lasting legacy into adulthood

Researchers are increasingly realising that impaired placental function can have a lingering impact on a baby’s long term health. An example of this is pre-eclampsia, a condition that causes high blood pressure in pregnancy, and is associated with altered placental function. Babies whose mothers had pre-eclampsia during pregnancy are at greater risk of heart disease in adulthood, for reasons not yet understood.

“It’s now known that many factors during pregnancy – such as a mother’s diet, and whether she was overweight or had diabetes, can impact the baby for life. And the placenta is likely to play an important part in this,” adds Dr Holder.

Crossing the placenta

Many substances that the mother is exposed to – such as alcohol, caffeine or nicotine, will travel across the placenta from the mother’s blood to the fetus.

Scientists are still unsure about why some pathogens such as the rubella and Zika viruses potentially travel across fairly easily, while others don’t, adds Dr Holder.

Exosome 'parcels' (red) absorbed by placenta cells (blue)

Dr Holder’s work focuses on how protection against bacteria and viruses can travel across the placenta from the mother to the fetus.

We know that antibodies from the mother’s immune system can travel across to the fetus to help provide temporary protection to the baby in the first weeks of life. This is why pregnant women are advised to get the whooping cough vaccine, as this helps boost antibody transfer to the baby- this is called maternal immunisation. Part of Dr Holder’s research aims to investigate the impact of maternal immunisation on the baby’s immune system at birth and the first months of life.

In Dr Holder’s work, for which she was awarded her prize, she studied tiny microscopic ‘parcels’ called exosomes that help cells of the body communicate with each other. Each tiny parcel, which are produced by cells in the body, contains messages that are picked up and read by other cells.

Dr Holder explains: “For instance, if a cell is infected by a virus or bacteria, it can release exosomes into the bloodstream containing messages warning other cells there is an infection.

In a recent paper, published in the journal Traffic, Dr Holder showed that the placenta receives exosome parcels from the mother’s immune system.

These may carry messages, or even parts of a virus or bacteria, that will help the placenta and the fetus to recognise the pathogen and fight the infection.

She adds that unravelling how substances travel across the placenta could provide life-saving insights for babies in the womb. “For instance, if we know a mother has a particular illness or disease, we could try to block this transferring to the baby. Or if the baby is not growing properly, we could try to increase the flow of nutrients across the placenta to help it thrive. There is still so much to find out about this organ – it holds unlimited potential.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Kate Wighton

Communications Division