From McDonalds to the Data Science Institute: My Bitcoin Experience

by Harry Pettit

Master's student Harry Pettit investigates the strange new world of bitcoin with a visit to Imperial's Data Science Institute.

When I set out on a journey to find out more about cryptocurrencies, I hadn’t envisioned myself meeting a complete stranger outside McDonald’s on Camden High Street.

For all of the misgivings I had in the lead up to our ‘deal’, Daniel looked entirely normal and shook my hand with a warm, friendly smile.

Harry Pettit

“Right, shall we head inside?”

We’d arranged the meet-up via popular trading website LocalBitcoins, where sellers post an ad with a price per Bitcoin. The site has a traffic light system for reputation; Daniel boasted an excellent rating of 96% positive reviews. Yet my stomach tensed as I slid the cash across our small, plastic table.

I gave Daniel my 33-digit Bitcoin ‘wallet code’ – a digital address that people can send Bitcoins to – and he transferred the amount via a laptop he had brought with him. A poultry 0.165BTC (around £50) popped into my digital wallet almost instantly, which I was able to track via an app on my phone. The transfer was done.

Handing a wad of cash over a table in McDonald’s tends to draw funny looks, so we left shortly afterwards. As we parted ways, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the ‘deal’ had left me with far more questions than answers…

Seeing is believing

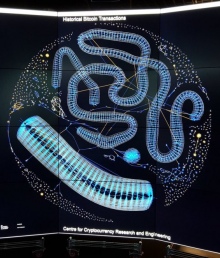

A couple of weeks later I visited Imperial’s Data Science Institute, housing one of the most advanced data visualisation platforms in the world – which, amongst many other applications, is being used to navigate the digital labyrinth of Bitcoin transactions.

Imperial graduate Dan McGinn, who masterminded the project during his MSc in Computing Science last year, showed me around. “Bitcoin has really gathered pace, with even big companies like Microsoft trading in it,” he explains as we enter the demo room. “It’s decentralised, there are no bank charges; it’s the first truly global currency.”

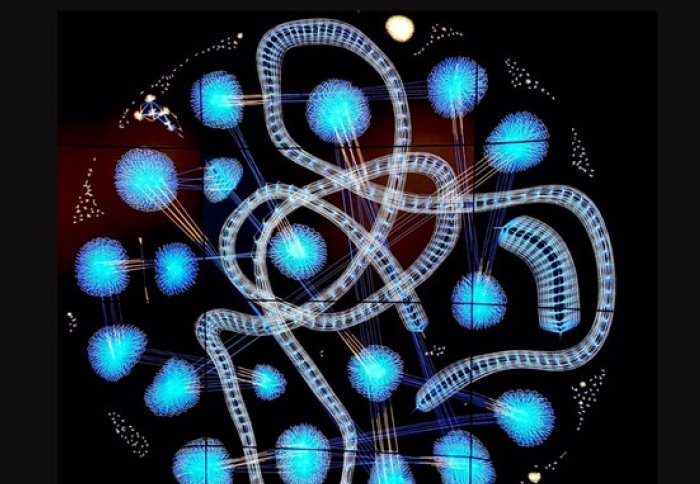

A wall of 32 large computer screens, curved into a horseshoe in the centre of the room, looms before us. Reams of short lines dance complex geometric shapes across them, each representing a real-time Bitcoin transaction somewhere in the world.

BBC journalist Spencer Kelly visits the Data Observatory in December 2015

“The reason Bitcoin works is that every transaction is public,” Dan explains as my eyes gather in the tangle of data before me. “Transactions are organised into ‘blocks’ of data that are laid bare for everyone to see, a consensus can then be reached as to whether each transaction actually happened and this stops people claiming they sent Bitcoin when they didn’t.” The wall of screens splits into several segments, each looking at Bitcoin trades in different ways.

“The point of the project was to shed light on new ways of reading intricate data,” Dan explains, “we wanted to create patterns where you would otherwise have an illegible, Matrixstyle stream of figures.”

Each transaction is shown as a line between a ‘buyer’ and ‘seller’, with large traders sprouting multiple lines at a time across the globe. Visualisations such as these can reveal which of these trades were ‘human’, and which trades were automated (via a computer programme) by the shapes they produce.

Defensive position

I’m drawn to one particular segment, in which thousands of small transaction lines twist and wind over one another into a serpentine, spinal column of data.

“This represents a massive spam attack on the Bitcoin system that occurred last year,” Dan reveals. “It’s attacks like this, in which a lot of money can be lost, that serve to undermine the currency’s awesome potential.”

“This represents a massive spam attack on the Bitcoin system that occurred last year,” Dan reveals. “It’s attacks like this, in which a lot of money can be lost, that serve to undermine the currency’s awesome potential.”

The Bitcoin system is limited to three to seven transactions per second − low compared to other financial systems. If you create an algorithm to overload the system, then the whole thing breaks down and transactions can take 12–14 hours to complete. This gives the attackers a perfect window to help themselves to bitcoins in digital wallets with weak passwords, as the security of the communal system is briefly lost.

Using data visualisation systems such as Dan’s, we can compare attacks like this to ‘normal’ trades and spot key visual differences. These transactions were evidently not human - the snake-like column looks much more purposeful and calculated – peeling back the sheepskin to reveal the algorithmic wolf beneath.

Yet despite attacks such as these, Dan is optimistic. “I truly believe that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are the future of economics.”

Find out how Imperial staff and students are unlocking the power of bitcoin technologies for the benefit of society.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Harry Pettit

Communications and Public Affairs