Natural variation caused temporary cooling at Antarctic Peninsula, shows study

by Simon Levey

Gentoo penguins jump into Antarctic ocean

New research suggests rapid warming at the Antarctic Peninsula has 'paused' but this does not mean global warming has halted, says an Imperial expert.

The northern sector of the Antarctic Peninsula, which sticks out from the main continent, was one of the regions of the world where warming was greatest during the early 1950s to the late 1990s. Now it has levelled off whilst other areas of the world continue warming, according to a study published by British Antarctic Survey (BAS) this week in the journal Nature.

"Scientists have long understood that global warming reflects an average change in climate across the planet. This means it won't lead to temperatures rising at the same rate continuously, everywhere and at once - and some areas will cool," explained Professor Martin Siegert, co-director of the Grantham Institute - Climate Change and the Environment, at Imperial College London.

Professor Siegert is a leading Antarctic glaciologist who has led many research campaigns to investigate changes to the Antarctic ice sheets. He gave his expert view on it at a press conference on Tuesday.

Although the peninsula has entered a temporary cooling phase, temperatures remain higher than those measured during the middle of the twentieth century and Antarctic glaciers are still melting. The study’s authors predict that if greenhouse gas concentrations continue to rise at the current rate, temperatures will increase across the Antarctic Peninsula by several degrees Celsius by the end of this century.

Lead author, Professor John Turner of British Antarctic Survey said: "The Antarctic Peninsula climate system shows large natural variations, which can overwhelm the signals of human-induced global warming.

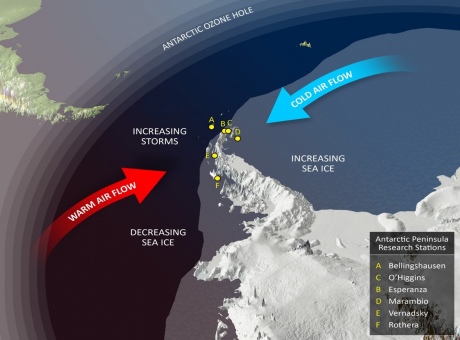

"Our study highlights the complexity and difficulty of attributing effect to cause. The ozone hole, sea ice and westerly winds have been significant in influencing regional climate change in recent years. Even in a generally warming world, over the next couple of decades, temperatures in this region may go up or down, but our models predict that in the longer term greenhouse gases will lead to an increase in temperatures by the end of the 21st Century."

A wide range of climate data was analysed for this study, including atmospheric circulation fields, sea-ice records, ocean surface temperatures and meteorological observations from six Antarctic Peninsula research stations with near-continuous records extending back to the 1950s.

Climate influences on the Antarctic Peninsula

Professor Siegert said, "This study uncovers an important interplay between the ozone layer and the wind in of the world's most challenging and extreme environments."

"It begs a question as to the climate variability in other regions of Antarctica - where there is far more ice with the potential to melt and cause sea-level rise - as well as in the Arctic and other locations."

In the last month, the levels of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide in the atmosphere above Antarctica rose past the 400 parts per million milestone, contrasting with the pre-industrial level of 280 parts per million recorded in Antarctic ice cores. Climate model simulations predict that if greenhouse gas concentrations continue to increase at currently projected rates their warming effect will dominate over natural variability (and the cooling effect associated with recovering ozone levels) and there will be a warming of several degrees across the region by the end of this century.

"While it is true, as some have pointed out, that Antarctic melting is predominantly affected by the warming ocean, we cannot exclude the effect of atmospheric conditions," Professor Siegert added.

Floating ice shelves border much of the continent, and act as a buttress that prevents ice from flowing from the land into the sea. When warmer air temperatures cause the surface of the ice shelves to melt, this can lead to them rapidly disintegrating.

Floating ice shelves border much of the continent, and act as a buttress that prevents ice from flowing from the land into the sea. When warmer air temperatures cause the surface of the ice shelves to melt, this can lead to them rapidly disintegrating.

"This is particularly worrying, as the Antarctic land ice could be lost much faster without the support from the ice shelves, making them more vulnerable to the effects of climate change," Professor Siegert explained.

Scientists are now pursuing further research to understand how the variability in climate affects global temperature conditions.

"We will be in a better position to predict how Antarctica may change in the coming century," said Professor Siegert.

Adapted from a press release by British Antarctic Survey.

Read more

Absence of 21st century warming on Antarctic Peninsula consistent with natural variability by John Turner, Hua Lu, Ian White, John C. King, Tony Phillips, J. Scott Hosking, Thomas J. Bracegirdle, Gareth J. Marshall, Robert Mulvaney and Pranab Deb. Nature doi:10.1038/nature18645

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Simon Levey

Communications Division