Imperial professor set to steer the UK Space Agency

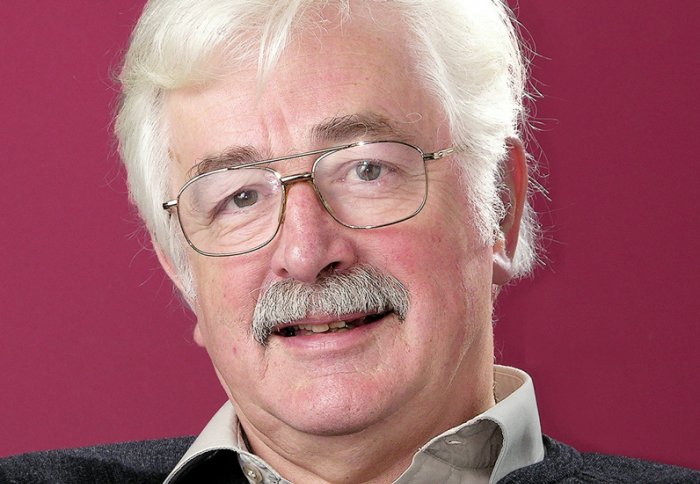

Professor David Southwood has been appointed to a top role the UK Space Agency as it navigates Brexit and celebrates Tim Peake's success.

Professor Southwood is a Senior Research Investigator in the Department of Physics at Imperial, focusing on solar-terrestrial physics and planetary science. He has also been the Director of Science and Robotic Exploration at the European Space Agency and President of the Royal Astronomical Society.

For my grandchildren, the most impressive thing I’ve ever done is to know Tim Peake!

He now takes on a new role as Chair of the Steering Committee for the UK Space Agency, which advises the agency on its strategic direction. Hayley Dunning sat down with him to discuss the strengths of the UK space industry and what the future holds.

Congratulations on the new role! What are you looking forward to?

It’s particularly exciting to take it on at the moment where we have to redefine everything and redesign it because there’s been a vote to leave the European Union. Space is one thing this country hasn’t been able to do on its own, ever. In the early 1960s we chose to go with the Europeans, so we have more than 50 years of cooperation with Europe.

We will remain in the European Space Agency and we will remain in the EUMETSAT [European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites] but we will not remain in the EU, and that’s increasingly where space for everyday life is being organised – navigation systems and environmental monitoring, and so on. So we’ve got a real challenge, and I guess I like living a difficult life!

What areas of space is the UK involved in?

We’re involved in most major space science satellite programs, we have a large commercial market in telecommunications satellites. Space is expensive to join in, launching something is expensive for example, and so when you’re building a big satellite you spend an enormous amount of time testing it to make sure it won’t fail.

CubeSat. Image: NASA

However, we’ve also got quite creative small satellite and CubeSat [miniature satellite] companies that do think in a different way. The breakthroughs are when you can do it so cheaply that you can afford to lose a satellite. There’s a great tension in the space game between absolute quality assurance, which is our tradition, and the idea that if you can make them cheaply enough and miniature enough that you can afford to lose a few.

What do you think will change in the next 20 years?

The way we use space-based technologies every day. It’s opening up – you already use GPS and other things you are not even aware of. It’s because space gives you global coverage. It’s surveillance of our environment, it’s communications on any part of the globe and it’s getting internet anywhere.

We’re landing on Mars in a couple of months’ time, a mission has just arrived around Jupiter, and we’ve seen back to the origin of the Big Bang. Space exploration is still mind-expanding in that regard; it’s just that the everyday aspect is economically important. The inspirational aspect is important for getting people to understand what the technology can do. But the everyday aspects allows them to do things they never could have done before.

Speaking of the inspirational aspect, what do you hope for the outcomes of Tim Peake’s mission?

The UK from space. Image: Tim Peake/ESA

From the space station, he had contact with one million school children in Great Britain. For my grandchildren, the most impressive thing I’ve ever done is to know Tim Peake! What’s wonderful about being an astronaut is that you can take people with you. All those kids went with him. There are barriers to people becoming scientists that are largely psychological. Finding a scientist with personality who can lead you on is really important.

I would always be happy to see more UK people in space – the extraordinary manner in which Tim Peake took us along with him shows us it’s important to have astronauts. We have unmanned airplanes and driverless trains, but people relate to people.

What do you think of criticisms of human spaceflight being too expensive and we should stick to robotic space exploration?

You can say that it costs so much, but you can’t gauge the absolute economic return. If somebody takes you out of the everyday into thinking the sky’s the limit, how do you value that?

Robotic and human exploration are different. Humans in space take us all up there. I have a rule. One of the disappointments of my career is never having been in space. I’ve been there psychologically, thought myself there, instruments I’ve built have been there, but I’ve never been there myself. I think if you’ve ever thought ‘I’d love to do that’ you can’t object to some level of human spaceflight.

You built the magnetometer instrument aboard the Cassini spacecraft. How did your career lead you from building space missions to leading them?

I was head of Physics at Imperial 20 years ago, before I went into the European Space Agency. The point at which I went in was when we launched Cassini - the same month - but it wouldn’t get to Saturn for seven years.

Impression of Cassini at Saturn. Image: ESA/NASA

I figured I would take three years out from Imperial to set up a new Earth Observation programme at ESA. But when that was finished, I had the opportunity to become the Director of Science there, looking in the opposite direction – instead of looking at the Earth, looking out to the Solar System.

That was terrific fun because it was a time when Cassini got to Saturn, and my instrument started working. I handed over responsibility to Michele Dougherty [Department of Physics] and I found myself in charge of landing on Titan with the Huygens probe. We were building Rosetta and had launched it that same year. It’s long term when you work in space!

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division