What role does scar tissue play in recovery from heart disease?

Researchers explore whether helping make better scar tissue in your heart could be a possible alternative to re-growing new tissue.

Heart disease is the number one cause of death globally, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), affecting millions of people every year. In addition many people are incapacitated by or recovering from heart disease. Internationally there are a lot of scientists working on better treatments for those who suffer from heart attacks. The Cardiac Biophysics and Systems Biology team, lead by Professor Peter Kohl, at the Harefield Heart Science Centre has recently reviewed one unusual aspect of the research in this area. Their findings, printed in today’s issue of Nature Reviews in Drug Discovery, suggest that we should be working with nature to improve her natural response to heart damage – the formation of scar tissue.

Scar tissue growing in your heart is nature’s way of repairing cardiac tissue damage. While damage in itself is a bad thing, this repair mechanism is vital. Scars prevent the mechanical failure of your heart’s pumping action, which keeps our blood moving around our body, and us alive. But scar cells (called cardiac fibroblasts) also have side effects as they can obstruct the electrical signals that control the coordination of this same pumping action by the heart. This has led to fibroblasts being thought of as a 'the problem', rather than ‘the solution' to what otherwise would be instant death.

Current research in this area, including the work of Professor Peter Kohl of the National Heart & Lung Institute (NHLI), is exploring whether improving repair of heart tissue (i.e. making better scars) is a therapeutically valid option that may be within easier reach than cardiac regeneration (making new muscle). So instead of fighting the scar, which has proved hard to achieve, we should aim at 'making better scars' by targeted improvements in scar properties.

Fibroblasts are the cells in our bodies responsible for building the structural framework for our tissues, and cardiac fibroblasts carry out this job in our hearts, to provide support for components like blood vessels and muscle cells. We also know these cardiac fibroblasts play a role in signaling in the heart, and in the formation of scar tissue that helps to repair the heart after an injury, such as myocardial ischaemia (when blood flow to your heart is reduced). The cardiac fibroblasts key role in scar formation also makes them crucial to heart repair after traumatic events such as surgery.

New research is already looking at how we can work with the cardiac fibroblasts to help recovery from heart disease. Several existing drugs act, at least partially, through effects on heart connective tissue. This latest review in Nature looks at how fibroblasts work in the heart, at current treatments that involve them, and it identifies future targets for research and development. The aim is that in ten years’ time people suffering from a heart attack could be put in a scanner to assess the damage to their heart, and then receive an injection to allow their bodies to build ‘better’ scar tissue, helping them to recover more successfully. The injection could contain genetically targeted information, that affects the cells that participate in heart tissue repair, to enhance their capabilities. This enhancement may be that the scar tissue grows to be mechanically more similar to the heart muscle around it, as natural scars often 'overcompensate', forming very stiff tissue. Or the injection could allow the fibroblasts to passively conduct electrical signals between surrounding heart muscle cells, making the scars 'electrically invisible'. In fact targeting strategies have already been developed to make fibrobalsts express new proteins when they repair the heart and these are being tested in animal research, so hopefully we are on our way to achieving this goal.

This latest review was carried out by Professor Peter Kohl of NHLI in collaboration with Professor Robert Gourdie of Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, and Professor Stefanie Dimmeler of the University of Frankfurt.

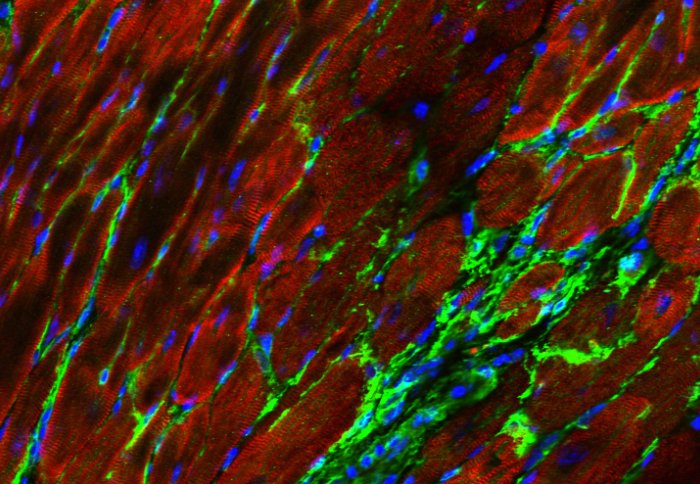

Photo credit: Dr. Patrizia Camelliti (NHLI & University of Surrey).

Photo description: Image of cardiac muscle cells (red) which, after an injury are replaced in scar tissue by fibroblasts (green). The non-muscle cells in this tissue can be genetically targeted to express non-native proteins (here a fluorescent marker). Such celltype-specific targeting is hoped to allow us in future to steer cardiac scar properties to patient benefit. Blue = cell nuclei.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Ms Helen Johnson

Communications Division