Three ways Imperial scientists are leading the fight against HIV/AIDS

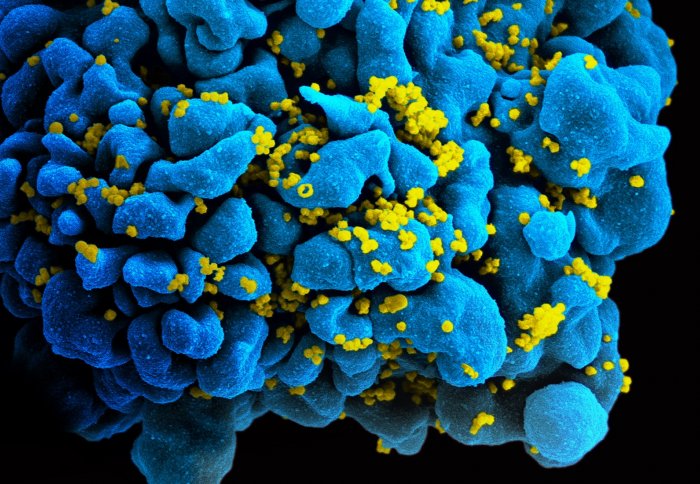

An HIV-infected H9 T-cell

World AIDS Day is held on 1 December each year as an opportunity for people around the world to unite in the fight against HIV.

The advent of antiretroviral therapy, introduced in 1995, has transformed the lives of those living with HIV. Globally, around 17 million of the 34 million HIV-positive people now have access to this treatment, which can leave them with a life expectancy almost that of someone uninfected.

There is clearly still a long way to go to treat everyone with HIV, and we still do not have a cure for those infected. Here we look at three ways Imperial scientists are leading the way in the fight to achieve these goals.

1 – Scientists have developed a rapid HIV test on a USB stick

The device, created by scientists at Imperial College London and DNA Electronics, uses a drop of blood to detect HIV, and then creates an electrical signal that can be read by a computer, laptop or handheld device.

This new technology is not only very accurate, but can also determine the amount of virus in the bloodstream in under 30 minutes. Assessing this ‘viral load’ is crucial to monitoring a patient’s treatment.

This new technology is not only very accurate, but can also determine the amount of virus in the bloodstream in under 30 minutes. Assessing this ‘viral load’ is crucial to monitoring a patient’s treatment.

In some cases the anti-retroviral treatment stop working – perhaps because the HIV virus has developed resistance to the drugs. The first indication of this would be a rise in virus levels in the bloodstream.

Senior study author Dr Graham Cooke explained: “Monitoring viral load is crucial to the success of HIV treatment. At the moment, testing often requires costly and complex equipment that can take a couple of days to produce a result. We have taken the job done by this equipment, which is the size of a large photocopier, and shrunk it down to a USB chip.”

2 – HIV infection rates could be halved by ramping up existing strategies

Imperial researchers, in collaboration with the Stichting HIV Monitoring Foundation, conducted this study on data collected from almost all men having sex with men (known as MSM) in the Netherlands.

Their work suggests that using a combination of more comprehensive annual HIV testing, together with rapidly treating infected men, and even treating some uninfected men (known as prophylactic treatment), could reduce new cases of HIV infections.

Their work suggests that using a combination of more comprehensive annual HIV testing, together with rapidly treating infected men, and even treating some uninfected men (known as prophylactic treatment), could reduce new cases of HIV infections.

The results showed that 71 per cent of new infections were from men who did not know they were infected – and almost half of all transmissions occurred from men in their first year of infection.

Dr Oliver Ratmann, lead author of the study from Imperial’s School of Public Health said: “The question we needed to answer was why new HIV diagnoses haven’t significantly reduced, despite antiretrovirals being available since 1996."

"The findings of this study support making more broadly available antiretrovirals for prophylactic use by uninfected individuals in the MSM community."

3 – Researchers are coming together to find a cure for HIV infection

The CHERUB collaboration brings together five UK Biomedical Research Centres to engage internationally in one of the most exciting new fields of biomedical research – that of an HIV cure.

Although antiretroviral therapy can reduce the level of HIV in the blood to undetectable levels, the virus survives in latent reservoirs. These latently infected cells can be reactivated and start producing HIV again, meaning that antiretroviral therapy can’t cure HIV infection.

Imperial’s Professor Sarah Fidler is working as part of a trial taking an innovative approach to developing a cure by trialling a two-step method with patients on antiretroviral therapy. They aim to use a drug to first awaken the latent viral cells in patients, and then use the patient's own immune system to kill them.

Professor Fidler, who runs clinics for people with HIV at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, talked about this trial and current treatments for HIV at a recent Imperial College AHSC seminar.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Mr Al McCartney

Faculty of Medicine Centre