Explosions, Nobel Prizes and poems: a history of the Department of Chemistry

Frances Micklethwait

A new book follows Imperial's Department of Chemistry from 1845-2000, exploring its most famous figures, innovative research and colourful characters.

The Department of Chemistry was born long before Imperial College London existed. Its oldest roots are in the Royal College of Chemistry, founded in 1845 with the help of Prince Albert, and its charismatic first professor was A.W. Hofmann, one of the foremost of all organic chemists. Since then, it has changed names, locations and chiefs, but has always been a leader in the field, according to a new history published this year by two chemistry alumni.

One of the chemistry labs in 1912

Professors Hannah Gay and Bill Griffith both completed chemistry degrees at Imperial. Professor Gay later moved on to study the history of science, and she was commissioned by Imperial to write The History of Imperial College London 1907-2007 to mark the College’s centenary. Professor Griffith still has an active role in the Department, continuing a distinguished career in inorganic coordination chemistry.

The Department has produced three chemistry Nobel Prize winners and been instrumental in the development of a huge variety of topics in organic, inorganic, physical, materials and computational chemistry as well as nanochemistry.

But its history is more than achievements and great minds. Professor Griffith picked out some of his favourite and most noteworthy stories from the book to illustrate some of the character of the Department – there are many others in the book.

Frederick Field's chemical verse

In the early days of the Royal College of Chemistry, Frederick Field (who joined in 1858, and after whom the dyestuff Field’s Yellow is named) distinguished himself as the ‘College poet’, penning lines like:

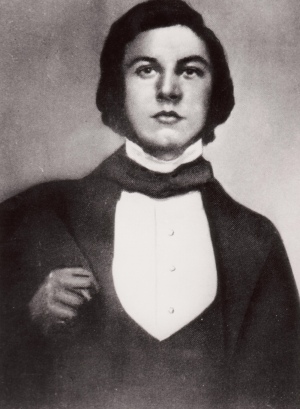

William Perkin in 1852, one of the very first ‘selfies’

F surely stands for FARADAY, and F should stand alone

The letter of the alphabet, the chemist of the throne.

And:

Thrice welcome Frankland, every one will say

Hail to the rising chemist of the day!

Father of Ethyl! that portentous birth

Which to its very centre shook the Earth

And:

Of purple PERKIN next we sing, a very clever cove,

Whose name in every nation is identified with mauve.

The Perkin named above was William Perkin, renowned for creating the silk dye later called mauveine. Perkin patented his invention and set up a successful London factory to make it and other dyes. He is often called the founder of British chemical industry.

War stories: Explosive liquids and invisible inks

Members of Imperial's Department of Chemistry also served in the Home Guard at Buckingham Palace

Imperial’s was the only chemistry department to remain open during the Second World War, and much defence-related research was carried out there, including work on the production of penicillin, vitamins A and B1, incendiary devices, and antidotes to poison gases. Other projects included making tablets that looked like aspirins but which, when introduced into chemical vats, ate holes through the walls.

Researchers also experimented with ways to put cars out of action by adding something to the petrol. Researcher Alexander King was given a car to carry out experiments – which he did on the roads within Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park.

At first nothing worked well, and King said: “The car seemed to enjoy every foul mixture we fed it.” But then he experimented with a substance (the toxic and explosive liquid, nickel carbonyl) that might coat spark plugs and halt the car.

King brought a quart of the liquid in a thick glass bottle with him on a train from Wales, but he ran into two bombing raids on the way. He feared that he and his fellow passengers would be killed – either by a direct hit or, were the bottle to break, by poison. In the end, he made it safely back to London, but the substance was deemed too dangerous to be of any practical use.

Martha Whiteley and Derek Barton

In WWII, two later Nobel laureates from Imperial were also involved in research when they were research students there. Derek Barton (Nobel 1969) worked on invisible inks, and Geoffrey Wilkinson (Nobel 1973) was seconded by the department in 1943 to work on the Tube Alloys project in Canada – a codename for the atomic bomb project.

The Department was also open during the First World War, and benefitted from the pioneering work of, amongst others, two of its female researchers, Frances Micklethwait and Martha Whiteley. Micklethwait, for example, worked on antidotes for mustard gas. Both women joined the Department in the 1890s, despite the many professional barriers to women at the time.

Flashes and bangs! Health and safety in the 1950s

One researcher, Eddie Abel, went on to have a prestigious career, but is perhaps best remembered in the department for causing an explosion in the 1950s. The blast blew out some windows as well as the door to his supervisor Professor Geoffrey Wilkinson’s office, and there was a spectacular fire in Abel’s lab, adjoining that office.

A first-year undergraduate remembers Wilkinson being ‘ten minutes into his lecture when the double doors of the lecture theatre bowed inwards’. The building shook, people outside the doors were running around shouting, and some were unravelling fire hoses. Wilkinson, however, carried on lecturing until someone came and grabbed him saying: ‘Professor Wilkinson, please come!’

But he soon returned ‘grinning’, picked up his chalk, and resumed the lecture. The students then stamped their feet causing him to pause and say: ‘Oh, you want to know what is going on... well my lab’s on fire from floor to ceiling but there is nothing I can do about it’.

Abel was told that on no account was the experiment that caused the explosion to be attempted again in any of the departmental laboratories. Undeterred, Abel came to the department very early on Saturday mornings and prepared the compound on the spacious fire escape outside the lab.

He wore three lab coats and a big towel around his head for protection. There were some more flashes and bangs, and with them came huge clouds of grey-green smoke. Some construction workers, working overtime on the new wing of the Science Museum, were amused witnesses and after each bang shouted ‘do it again prof’.

Moving on: White City on the horizon

Imperial’s chemistry department is rooted in the past but has always looked to the future. This has not always gone smoothly.

In the mid-1980s a proto computer network came to the department when a copper cable was installed connecting the Chemistry building to the computing centre in the mechanical engineering building.

Professor Henry Rzepa relates that, when exploring how to connect the two South Kensington chemistry buildings electronically, he crawled through some underground tunnels, lost his way, and surfaced via a manhole cover in the floor of the men’s toilet, scaring the lone occupant who immediately fled.

An impression of the Molecular Sciences Research Hub building upon completion

Although the book covers the period up until 2000, Chemistry will be the first department to start a fresh chapter for Imperial, by moving its research hub out to the new White City campus in early 2018. The Molecular Sciences Research Hub aims to drive a new way of doing chemistry that transcends disciplinary and institutional boundaries in the search for solutions to some of the great challenges facing humanity.

-

The Chemistry Department at Imperial College London: A History, 1845 – 2000 by Hannah Gay and William P. Griffith is published by World Scientific Publishing, Abingdon.

If you are Imperial chemistry staff, student or alumni, the publishers are offering a 25 per cent discount if ordered by 31 May 2017. For more information please contact Maria Tortelli.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division