Floating plastic pollution from Europe and the US is accumulating in the Arctic

Plastic waste entering the seas from both sides of the North Atlantic is accumulating in the Arctic Ocean, where it can damage local wildlife.

The low population of the Arctic Circle means little plastic waste is generated there. However, a new study has shown that the Greenland and Barents Seas (east of Greenland and north of Scandinavia) are accumulating large amounts of plastic debris that is carried and trapped there by ocean currents.

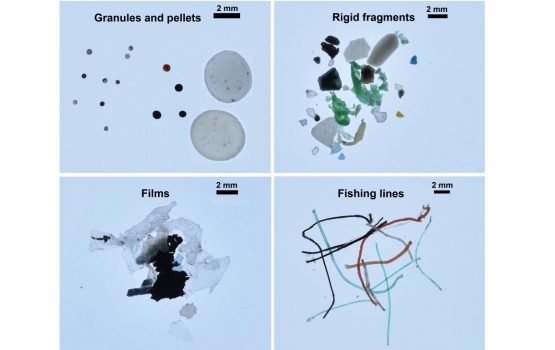

The new study, published today in Science Advances, found that the Greenland and Barents seas have accumulated hundreds of tons of plastic debris composed of around 300 billion pieces, mainly fragments around the size of a grain of rice. The vast majority of these fragments originate form the North Atlantic.

The team behind the study is composed of researchers from eight countries, led by Professor Andrés Cózar from the University of Cadiz in Spain, and including Dr Erik van Sebille from the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London.

Plastic is transported from the North Atlantic to the Arctic by the Gulf Stream, a huge ocean current that also carries warm waters from the Gulf of Mexico to northern Europe and the US east coast.

Once it gets to the Arctic Ocean, this current sinks and travels back to the equator, but the plastic does not sink with it, leaving it to build up in Arctic waters.

Ecosystem under threat

Plastic is a problem for local wildlife as marine organisms mistakenly eat, are poisoned by, or become tangled in floating plastic, which damages their health and can kill them.

Dr van Sebille, who now works at Utrecht University, said: "The Arctic is one of the most pristine ecosystems we still have. And at the same time it is probably the ecosystem most under threat from climate change and sea ice melt. Any extra pressure on the animals in the Arctic, from plastic litter or other pollution, can be disastrous.”

It is our plastic that ends up there, so we have a responsibility to fix the problem.

– Dr Erik van Sebille

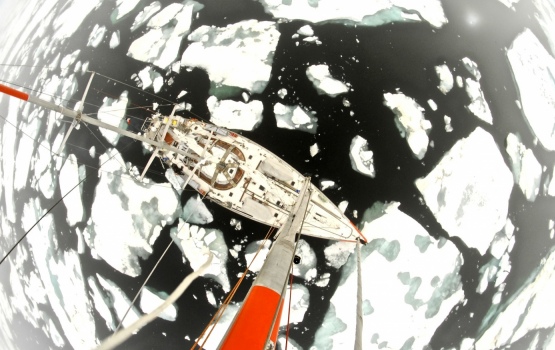

The team sailed on an expedition to the Arctic Ocean in order to complete a global map of floating plastic pollution. The expedition lasted five months and circumnavigated the Arctic ice cap aboard the research vessel Tara.

Professor Cózar said: “The plastic concentrations in the Arctic waters were usually low, but we found an area located in the north of the Greenland and the Barents seas with quite high concentrations. There is continuous transport of floating litter from the North Atlantic, and the Greenland and Barents seas act as a dead-end for this poleward conveyor belt of plastic.”

Prevention is the cure

To find the fate of plastic in the North Atlantic, team used data from over 17,000 drifting satellite-tracked buoys floating on the surface of the ocean. They then pieced together how the plastic ended up in the Arctic hotspots by using advanced statistics, which model how ocean currents move these buoys.

Dr van Sebille said: "What is really worrisome is that we can track this plastic near Greenland and in the Barents Sea directly to the coasts of northwest Europe, the UK and the east coast of the US. It is our plastic that ends up there, so we have a responsibility to fix the problem.

"We need to stop the plastic from going into the ocean in the first place. Once the plastic is in the ocean, it's too diffusive, too small and too intermingled with algae to easily filter out. Prevention is the best cure."

-

'The Arctic Ocean as a dead-end for the global plastic conveyor belt' by Andrés Cózar et al is published in Science Advances.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division