Saturn's 'weird' magnetic field perplexes scientists

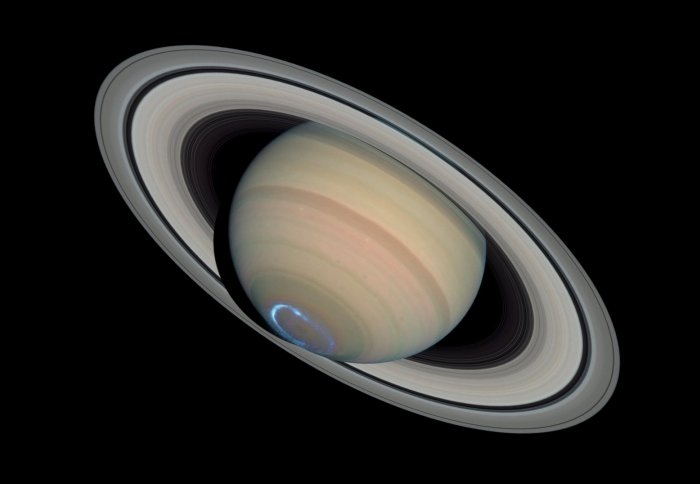

Saturn's magnetic field interacts with the solar wind and creates ultraviolet auroras. Image: NASA

The Cassini probe's first results from inside Saturn's rings make scientists question the conventional wisdom on how planets form magnetic fields.

As NASA's Cassini spacecraft makes its unprecedented series of weekly dives between Saturn and its rings, scientists are finding – so far – that the planet's magnetic field has no discernable tilt.

This is surprising, since scientists believe that for planets to generate magnetic fields, there must be a tilt between its rotation axis and its magnetic field axis.

For example, on Earth, while the geographic North Pole is located in the high Arctic Ocean, the magnetic north pole is off eastern Canadian Arctic islands.

Positions of the magnetic north pole

Earth’s magnetic north pole also migrates, affecting the strength of the magnetic field: currently it is moving northwards. Our magnetic field is important for shielding us from the solar wind and geomagnetic storms, which can severely disrupt communications and power grids on the ground.

Based on data collected by Cassini's magnetometer instrument, Saturn's magnetic field appears to be surprisingly well aligned with the planet's rotation axis. Previously, mission scientists thought that 0.06 degrees would be the lower limit of tilt that could generate the observed magnetic field. However, the results show the tilt may be much less than this.

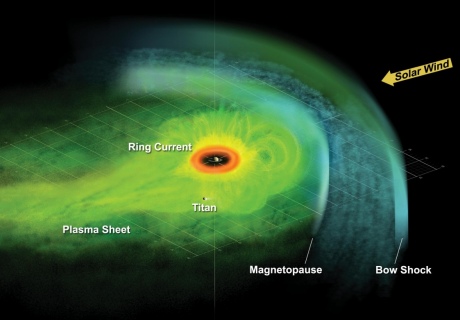

Scientists currently think that planetary magnetic fields require some degree of tilt in order to sustain currents flowing through the liquid metal deep inside the planets (in Saturn's case, thought to be liquid metallic hydrogen). With no tilt, the currents would eventually subside and the field would disappear.

How long is a day on Saturn?

The degree of tilt would also resolve the question of how long a day is on Saturn. This is currently unknown, because the swirling gases visible on the surface make it impossible to track a point on the surface as the planet rotates.

The spectacular science being revealed is a testament to the fantastic spacecraft and science teams that have enabled these Grand Finale orbits to happen. The observations so far from the magnetic field are very surprising and certainly not as we expected.

– Professor Michele Dougherty

Professor Michele Dougherty from the Department of Physics at Imperial, who leads Cassini’s magnetometer, said: "The tilt seems to be much smaller than we had previously estimated and quite challenging to explain. We have not been able to resolve the length of day at Saturn so far, but we're still working on it."

The lack of a tilt may eventually be rectified with further data. Professor Dougherty and her team believe some aspect of the planet's deep atmosphere might be masking the true internal magnetic field. The team will continue to collect and analyze data for the remainder of the mission, including during the final plunge into Saturn.

Cassini is now in the 15th of 22 weekly orbits that pass through the narrow gap between Saturn and its rings. The spacecraft began its finale on 26 April and will continue its dives until 15 September, when it will make a mission-ending plunge into Saturn's atmosphere.

The magnetometer data will also be evaluated in concert with Cassini's measurements of Saturn's gravity field collected during these final stages. Early analysis of the gravity data collected so far shows discrepancies compared with parts of the leading models of Saturn's interior, suggesting something unexpected about the planet's structure is awaiting discovery.

Artist's concept of the Saturnian plasma sheet based on data from Cassini. Image: NASA/JPL/JHUAPL

Professor Dougherty said: “The instrument and the spacecraft were originally designed to be in orbit at Saturn for four years and 13 years later we are still there and everything is in really good shape! What we should remember is that neither Cassini nor the instruments were designed to carry out these Grand Finale orbits.

"The spectacular science being revealed is a testament to the fantastic spacecraft and science teams that have enabled these Grand Finale orbits to happen. The observations so far from the magnetic field are very surprising and certainly not as we expected.”

Sampling Saturn

As well as investigating Saturn’s interior, Cassini has been able to make several other observation and sampling ‘firsts’ during its dives inside the rings. It obtained the first-ever samples of the planet's atmosphere and main rings, while its ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) has sniffed the outermost atmosphere, called the exosphere.

Close-up of Saturn's north pole, taken 18 July 2017. Image: NASA

Cassini's imaging cameras have also captured some of the highest-resolution views of the rings and planet they have ever obtained.

Cassini Project Manager Earl Maize at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California said: "Cassini is performing beautifully in the final leg of its long journey. Its observations continue to surprise and delight as we squeeze out every last bit of science that we can get."

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division