When collecting bird sperm, method matters

Different methods of collecting bird sperm produce different sperm lengths, potentially affecting the conclusions of fertility studies.

Scientists who are studying fertility in birds often use sperm length as an indicator of reproductive success. In birds, sperm length is a measure of how well the sperm can swim, and therefore their chance of success.

The size of the difference in average sperm length between sampling techniques is large enough to affect the outcome of analyses based on mixed methods.

– Antje Girndt

However, when collecting sperm, researchers often use a combination of different methods. Now, scientists at Imperial College London, the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Germany and the University of Linköping, Sweden have found different methods preferentially produce different lengths of house sparrow sperm.

This could potentially affect the outcomes of fertility studies. The results are published today in PLOS ONE.

The research team at Imperial College London, led by Dr Julia Schroeder, studies both a captive population of house sparrows and wild sparrows on the island of Lundy in the Bristol Channel. They look at questions of social behaviour and genetics, such as why sparrows ‘cheat’ on their partners.

To reach their conclusions, they often look at fertility, for example when trying to answer why females cheat with older males, who may be less fertile but more genetically ‘fit’.

Sparrow sperm

Lead author of the new study Antje Girndt, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial and the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, investigates how fertility changes with age. She said: “The size of the difference in average sperm length between sampling techniques is large enough to affect the outcome of analyses based on mixed methods.

“We would recommend avoiding mixing methods, or if that is not possible, then accounting for the differences when interrogating the data.”

The abdominal massage technique

Ms Girndt and colleagues tested three commonly used methods for collecting bird sperm: sampling faeces, female decoy and abdominal massage.

Reproductively active male birds lose sperm every time they defecate, just as human males can when they urinate, so collecting samples of faeces is a relatively simple method. However, this produced on average the shortest sperm in the study.

Ms Girndt believes there may be several reasons for this: “It could be that the sperm is not yet mature – the structure looks mature, but it may not have finished growing yet.

“Alternatively, it could be the poorest quality sperm. Sparrows have a short breeding season, and they replenish their stock overnight. This means they always need to have room for the best sperm.”

Previously, researchers have had success in using a dummy female when collecting sperm from zebra finches, which best represents a ‘natural’ situation, but it did not work so well with house sparrows. In this study, which involved placing a ‘presenting’ stuffed female on a perch with a male, the team failed to get enough samples for a proper comparison.

Video above: A trial with a dummy female

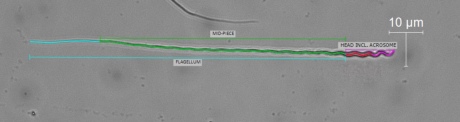

The third method is abdominal massage, which involves gently squeezing a swelling called the ‘cloacal protuberance’, whose main function is thought to be sperm storage and maturation. This method produced longer, potentially more mature sperm than the faeces.

Ms Girndt hopes the results of the study will help inform her and her colleagues’ own fertility work, as well as that of other researchers. She said: “In the past I have found that even changing the type of microscope I use affects the results of a study, so making sure we are as consistent as possible in our own methods is crucial.”

-

'Method matters: experimental evidence for shorter avian sperm in faecal compared to abdominal massage samples' by Antje Girndt, Glenn Cockburn, Alfredo Sánchez-Tójar, Hanne Løvlie, and Julia Schroeder is published in PLOS ONE.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division