More evidence Earth-like planets could sustain life as their atmospheres probed

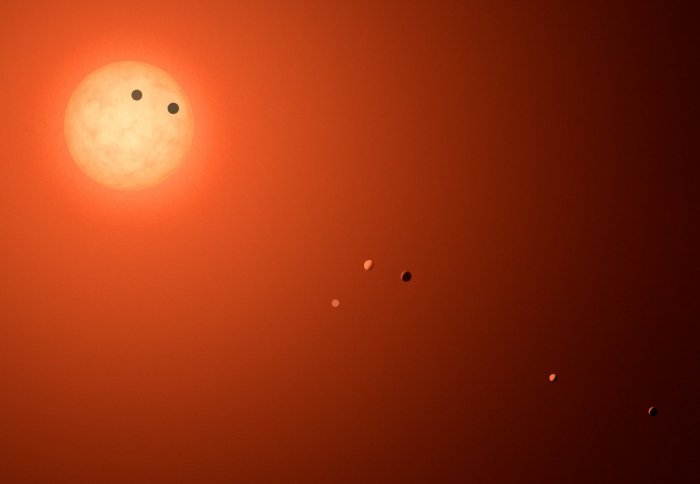

Artist's impression of the TRAPPIST-1 system. Credit: NASA

Three Earth-like planets orbiting the TRAPPIST-1 star have atmospheres that might be hospitable to life, a new study shows.

Researchers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope have analyzed the atmospheres of four Earth-sized extrasolar planets orbiting the nearby star TRAPPIST-1, located about 40 light-years from Earth.

These planets remain the best example of extra-solar planets that could have liquid water and possibly life on their surfaces.

– Dr James Owen

The planets orbit at a distance from the star that means their surfaces are potentially not so hot that liquid water would boil, but not so cold it would freeze, in a region called the ‘habitable zone’. Liquid water at the surface is thought to be one of the conditions necessary for life on other planets.

However, just being in the habitable zone does not mean liquid water is present – it also depends on the composition of the atmosphere. For example, if there is too much hydrogen or helium, and the atmosphere is ‘puffy’, there would be a strong greenhouse effect and the surface water would boil.

Now, an international team of researchers have conducted the first survey of the planets’ atmospheres, and revealed that at least three of them do not have ‘puffy’, hydrogen-rich atmospheres.

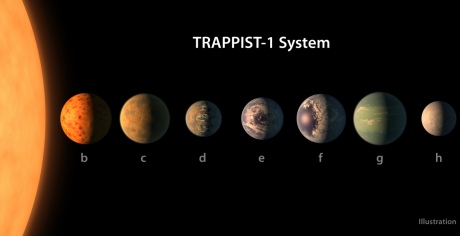

The results instead favour more compact atmospheres around rocky planets like those of Earth, Venus, and Mars. The study, which is the first to probe atmospheres of planets in a habitable zone, is published today in the journal Nature Astronomy.

On the right track

Co-author of the study Dr James Owen, now at the Department of Physics at Imperial, said: “These new observations show the atmospheres of the TRAPPIST-1 habitable zone planets do not contain large amounts of hydrogen and helium, meaning these planets remain the best example of extra-solar planets that could have liquid water and possibly life on their surfaces.

“This work is very exciting as it shows we are on the right track for trying to detect life on planets around other stars by being able to obtain a spectrum from the atmosphere of a planet residing in the habitable zone.”

Lead author Dr Julien de Wit, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, describes the positive implications of these measurements: “The lack of hydrogen envelopes supports further the terrestrial nature of the planets and is an important step in the exploration of those worlds ultimately aiming to determine if the planets harbor liquid water and/or organisms.”

The TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit a red dwarf star that is much smaller and cooler than our sun. In fact, the star is so cool that liquid water could exist on the surface of planets orbiting much closer to it than they would if they orbited a larger, hotter star like our sun. Red dwarf stars are the most common type of star, so there are many potential habitable planets are similar to those around TRAPPIST-1.

The TRAPPIST-1 planets complete an orbit in only a few days. As they cross the star, a small section of the star’s light passes through the atmosphere of the exoplanet and interacts with the atoms and molecules in it. This leaves a weak fingerprint of the atmosphere in the spectrum of the star, which is what Hubble detected.

Diverse planets

The planets may possess a range of atmospheres, just like the terrestrial planets in our solar system. Co-author Dr Hannah Wakeford, from the University of Exeter, said: “One of these four could be a water world.

“One could be an exo-Venus, and another could be an exo-Mars. It’s interesting because we have four planets that are different distances from the star, so we can learn a little bit more about our solar system, because we’re learning about how the TRAPPIST star has impacted its planets.”

The team plans to conduct follow-up observations in ultraviolet light to search for trace hydrogen escaping the planets’ atmospheres, produced from processes involving water or methane lower in their atmospheres.

By ruling out the presence of a large abundance of hydrogen in the planets’ atmospheres, Hubble is also helping to pave the way for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scheduled to launch in 2018. JWST and other next-generation telescopes will probe deeper into the planetary atmospheres, searching for heavier gases such as carbon, methane, water, and oxygen, which could offer signatures for life.

-

'Atmospheric reconnaissance of the habitable-zone Earth-sized planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1' by Julien de Wit et al is published in Nature Astronomy.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division