World Haemophilia Day: Q&A with Professor Mike Laffan

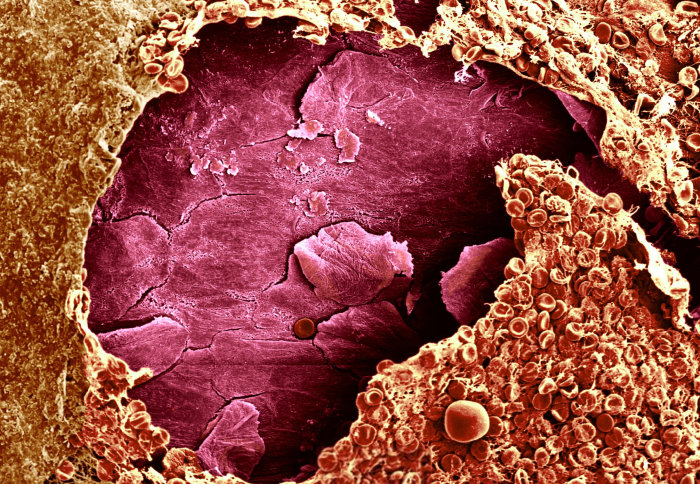

Blood clot forming over a wound

April 17 marks World Haemophilia Day, which this year focuses on the importance of sharing knowledge.

Established by the World Federation of Haemophilia, the aim of the day is to help increase awareness of the condition, and improve access to care and treatment.

Mike Laffan is Professor of Haemostasis and Thrombosis at the Centre for Haematology, Department of Medicine, and a member of The Imperial Network of Excellence in Vascular Science. We spoke to Professor Laffan in the lead up to World Haemophilia Day to discuss his latest research into gene therapy treatments, and his thoughts on raising awareness of the condition.

How has our understanding and treatment of haemophilia changed over the years?

In the 19th and early 20th century, haemophilia was generally regarded as a lethal disorder. People would suffer from recurrent bleeds into their muscles and joints. By the time these individuals reached early adulthood, they would have accumulated so much damage from these bleeds that they were often bedbound, and later died from resulting complications.

Then, in the later part of the 20th century, scientists managed to work out what was missing in these people’s blood. They made concentrates of the two clotting proteins that were lacking – factor VIII (haemophilia A) or factor IX (haemophilia B). In the seventies and eighties, blood was taken from thousands of people in order to extract the proteins needed. However, the devastating by-product of this was the transmission of hepatitis and HIV to around 5,000 people, many of whom died as a result.

Following this, scientists then began artificially manufacturing factors VIII and IX – these are known as ‘recombinants’. By creating these factors synthetically, the risk of transmitting hepatitis and HIV was eliminated. Under pressure from Members of Parliament and The Haemophilia Society, the Government started a ‘recombinant for all’ programme in the early 2000s. This means that everyone now has access to recombinant treatment, should they want it.

The next thing we’ve done is to treat people more intensively and make it possible for them to treat themselves at home. At the moment, the standard of care for someone with haemophilia A, for example, would be to inject themselves with factor VIII concentrate at home every other day. This is essentially what we call ‘replacement therapy’. We can now also deliver the concentrate to their home, and only need to check in with them every six months or so, unless they have a specific problem. We aim to prevent them from getting any bleeds at all, but this is often not completely successful and patients still develop arthritis as a complication.

Are there any alternatives to replacement therapy?

Until recently, the focus of progress has been to make safer, purer concentrates. In the earlier recombinant forms, there were some animal, as well as human, proteins present due to the manufacturing process. There were a series of developments to remove these, so recombinants are now completely free of animal and human protein.

In the last few years, we’ve seen the development of things like extended half-life products. These are factor VIII and IX molecules that have been modified to make them survive longer in circulation, so that you don’t have to inject so frequently. They’ve worked fairly well, but have not been quite as transformative as we would have hoped.

Another approach is a bit more complicated: it involves using something called ‘non-replacement therapy’. Scientists have created an antibody that mimics the effect of factor VIII in the body, and different companies are now looking at producing the things that counterbalance factor VIII, rather than replacing factor VIII itself. At all times in our blood, we have a balance of factors that help it to clot, and prevent it from clotting too much. One of the attractions of this counterbalancing exercise is that it avoids one of the complications of replacement therapy. For people who have no factor VIII in their blood, sometimes when we give them a recombinant, their body treats it as a foreign protein and starts producing antibodies – or inhibitors – which neutralise the treatment.

However, the ultimate goal is to get closer to a cure, and that really means gene therapy. When we talk about gene therapy, we are not necessarily correcting the faulty gene. What we’re actually doing is giving patients a new, functioning copy of the gene in question. At the moment, the way that works is to put the new gene inside a viral particle. These will generally migrate to the liver cells, where they then start producing factor VIII and IX. Interestingly, this isn’t the place that factor VIII is made normally: it’s typically produced in the lining of the blood vessels (endothelial cells). Liver cells are very good at making things and secreting them into the blood.

Is gene therapy now the focus of your research?

We’ve recently been running clinical trials at the NIHR Imperial CRF, the results of which were published at the end of last year. These are the first successful clinical trials in haemophilia A /factor VIII deficiency. All but one of the participants in the phase 1-2 study who received this high-dose gene therapy treatment ended up with levels of factor VIII that were in the normal range, and these levels were maintained a year later.

In one sense they’re cured, but, of course, we don’t know how long it will last. However, previous animal studies indicate that it could be for quite a while. Also, this treatment doesn’t fundamentally change a person’s genetic make-up, and they will still pass on haemophilia. It’s like a great big sticking plaster – but a highly effective one! As they now have normal levels of factor VIII, these individuals no longer have to inject themselves, they don’t suffer bleeds anymore, and they can pretty much do any activity they like.

We started the phase 3 study in December 2017, and the aim here is to find out what the ideal dose is for this treatment. All the participants are being followed-up continually to check that their factor VIII levels are as they should be.

What do you think are the most urgent questions that research needs to answer?

Everyone is very keen to find out whether we can get gene therapy right, and whether it really works in the long term. Unfortunately, some of these questions – particularly around safety – will only be answered after many years, because we need to monitor trial participants over an extended period of time.

We’ve developed treatments that undeniably work and can transform an individual’s quality of life – it’s crucial that everyone around the world has easy access to them Professor Mike Laffan

Another key question is, can we get cheap gene therapy for the rest of the world? We need to figure out how we can provide gene therapy to patients in developing countries. Depending on a country’s infrastructure and the funding available, it may be very difficult to organise the service as we’re able to organise it here. Patients elsewhere in the world may not be able to get access to recombinant home delivery, and therefore not able to self-inject. It may also be difficult for them to get to a hospital to receive regular treatment, or even be diagnosed with haemophilia in the first place. It would therefore be more efficient for them to attend hospital once to receive gene therapy treatment, which could then last for years.

The theme of this year’s World Haemophilia Day is “sharing knowledge”. How do you think we can better share knowledge about haemophilia with the wider public?

The World Federation of Haemophilia (WFH) World Congress is being held in Glasgow this year. It’s a slightly unusual scientific meeting because it’s attended not only by doctors, but by nurses, physiotherapists and patients. This is one way that you can share knowledge.

The treatment for haemophilia around the world is very patchy. This is partly because, historically, it’s been an expensive condition to treat. Patients and patient organisations in developing countries find it difficult to get enough funding allocated for haemophilia. However, the cost of treatment is steadily reducing. Part of what the WFH meeting will be about is how we can use and share resources more efficiently.

In some ways, there is a very mixed set of messages being sent out to the public when it comes to haemophilia. A new enquiry has been started in the UK into how the government handled the aforementioned HIV/hepatitis transmission by blood products. This was initiated because some people have been critical of how it was dealt with by health services at the time, predominantly in England. This might lead to some confusion about how we treat haemophilia today. One important thing to underline is that, whatever happened in the eighties, the prospects for haemophilia now are much, much better.

Why do you think awareness-raising incentives like World Haemophilia Day are important?

As with other diseases, haemophilia has to compete for funding. In order to do that, people not only need to be aware of what the problems are, but also what can be done about them; they need to see just how beneficial the investment can be.

By highlighting these important questions around the development of new therapies, it could help to drive funding. We’ve developed treatments that undeniably work and can transform an individual’s quality of life – it’s crucial that everyone around the world has easy access to them.

Find out more about World Haemophilia Day 2018

Images: David Gregory & Debbie Marshall | Wellcome Images

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Ms Genevieve Timmins

Academic Services