Is gravity and old mineshafts the next breakthrough in energy storage?

A new report by researchers at Imperial College London predicts that gravity-fed energy storage systems may provide long-term savings.

Analysis by a team based in the Centre for Environmental Policy, suggests that technology from the company Gravitricity is well suited to provide grid balancing and rapid frequency response services to grid operators.

While it has quite a high up front cost, with the better power-to-energy cost ratio and 25 year life span Gravitricity comes out looking like a compelling proposition. Oliver Schmidt Centre for Environmental Policy

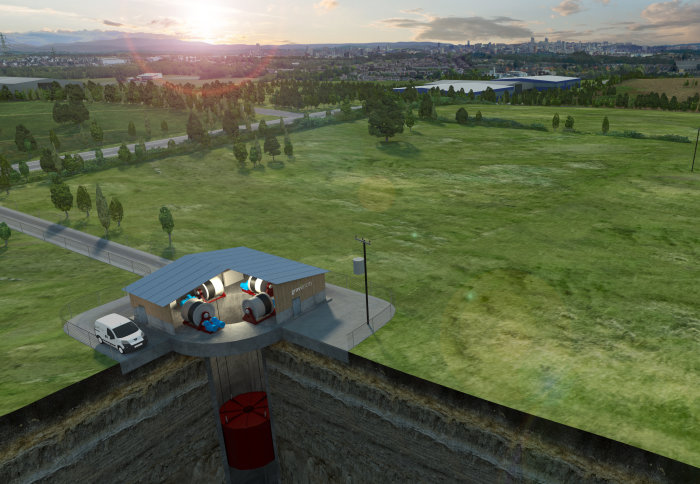

The company, led by an Imperial graduate, specialises in a gravity-fed energy storage system, which stores excess electrical power as potential energy. The idea is to suspend a large weight, up to 2000 tonnes, in vertical shafts and use excess electricity to winch it to the top of the shaft. The weight, and its energy, can then be released when required. Initial projects will be in existing mine shafts.

The Gravitricity team wanted an independent assessment of their technology and so at the end of last year commissioned Oliver Schmidt, a research postgraduate on the Science and Solutions for a Changing Planet DTP, to produce a cost assessment of their solution to the energy storage problem.

“I made sure our study was rigorous and compared all technologies on a level playing field,” Oliver says, “While it has quite a high up front cost, with the better power-to-energy cost ratio and 25 year life span Gravitricity comes out looking like a compelling proposition.”

The report takes into account a wide range of factors from the required initial investment and operating costs to potential degradation and changes to the cost of energy. The team concluded that the technology would be particularly well suited to help grid operators by providing grid balancing and rapid frequency response services.

Both Charlie Blair, Managing Director, and Miles Franklin, Lead Engineer, are graduates of the College and so it was natural for them to seek out researchers at the College to do the work.

“Miles and I wanted to really test the work we had done, so we came back to Imperial and talked to a few people to find out who would be suitable,” explains Charlie, “This is a first-of-a-kind project and we wanted to make sure we were working with the right people. Obviously we are happy with the conclusions and to see that we could be even more competitive in 2025 than we are now.”

To request a copy of the report please contact charlie.blair@gravitricity.com.

If you are interested in having researchers at Imperial College London conduct a similar study for your company please contact Imperial Consultants who will work with you to find a suitable researcher to work with.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Neasan O'Neill

Faculty of Engineering