WHO World No Tobacco Day: why the key to quitting smoking could lie in our guts

A team of researchers at Imperial College London is investigating whether gut hormones could play a vital role in helping people to quit smoking.

To mark WHO World No Tobacco Day 2018, we spoke to Dr Tony Goldstone, who leads the Gut Hormones in Addiction Study (GHADD) at Imperial College London, about his research into nicotine addiction.

Tell us about the work you’re doing to investigate the role that gut hormones play in nicotine addiction.

We are in the middle of a large Medical Research Council-funded study called the Gut Hormones in Addiction Study (GHADD). This is investigating whether some of the hormones in our gut, that we know regulate our appetite and food intake, may also play a role in altering how much we crave drugs like alcohol and nicotine. In animal studies, researchers have seen that gut hormones, such as ghrelin and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), not only alter how much food animals will eat, but also how much nicotine they consume.

We are undertaking the first study to investigate whether these hormones might also modulate how humans respond to cigarettes, with the aim of potentially developing a treatment to help people quit smoking. More specifically, we are studying people who were dependent on nicotine, and have recently given up smoking cigarettes. We know that statistically they have a high risk of relapsing. Right now, there is a need for better medications to help people get through this period. That is one of the things we are hoping to achieve in the future as a result of this study.

Another key issue that people face when they stop smoking is that they tend to gain weight. Although cigarettes are bad for you, the weight gain that often comes from stopping smoking can sometimes counteract some of the health benefits. In addition, people are put off quitting smoking in the first place because they are worried about putting on weight.

Interestingly, because the gut hormones we are investigating modulate appetite, they may have a double benefit in reducing cravings for both cigarettes and high-calorie foods. We are looking at whether we are able to target both with these potential treatments.

On this basis, is there the potential to develop one treatment for multiple addictions?

Yes, this is one of things we are investigating. We now know that these gut hormones operate via the brain circuitry that modulates our sense of reward, and also stress. What we have learnt from animal studies is that these hormones have an effect on many different “rewards” (e.g. nicotine, alcohol), because they are targeting the system in our brain that controls our cravings for all of these things.

What advantage does this investigation of gut hormones have over other approaches to tackling nicotine addiction?

There are a couple of drugs currently available to help people stop smoking, and they do have benefits. One of the potential issues with these treatments, however, is the way in which they target brain pathways, which can sometimes result in unwanted side effects.

Conversely, in the case of gut hormones, every time we eat food we change the levels of hormones in our blood. Therefore, the side effect profile of these hormonal-based therapies is small, because increasing the levels in our blood is a naturally occurring process. Secondly, the gut hormone approach can potentially target two of the key problems in nicotine dependence – stopping cigarette cravings as well as the weight gain that often comes after quitting. There isn’t any evidence that the drugs currently used to help with smoking cessation can do this.

What does the GHADD study entail, from a participant’s perspective?

We are looking for people who have stopped smoking at least six weeks ago, but not more than two years ago. At the start of the study, they need to have been off any form of nicotine replacement – for instance, nicotine patches, gum or vaping – for at least two weeks.

We are also recruiting a separate group of people, who were previously dependent on alcohol, and have stopped drinking between six weeks and five years ago. This group are allowed to be current cigarettes smokers.

The participants first come for a screening visit where we assess their eligibility. For safety reasons, we can’t study people who have diabetes or significant heart or lung problems. If they pass the screening visit, they will then come back for three study visits, which take place over a three- or four- week period. Each of those visits lasts for a whole day, but they do not need to stay overnight.

At one of those visits, they’ll be given a saline infusion, which acts as a dummy placebo. On the second visit, they’ll receive an infusion of one of the two different hormones that we’re studying: ghrelin, and a version of GLP-1. The participant and researchers won’t know on which day they’ll receive the different types of infusion.

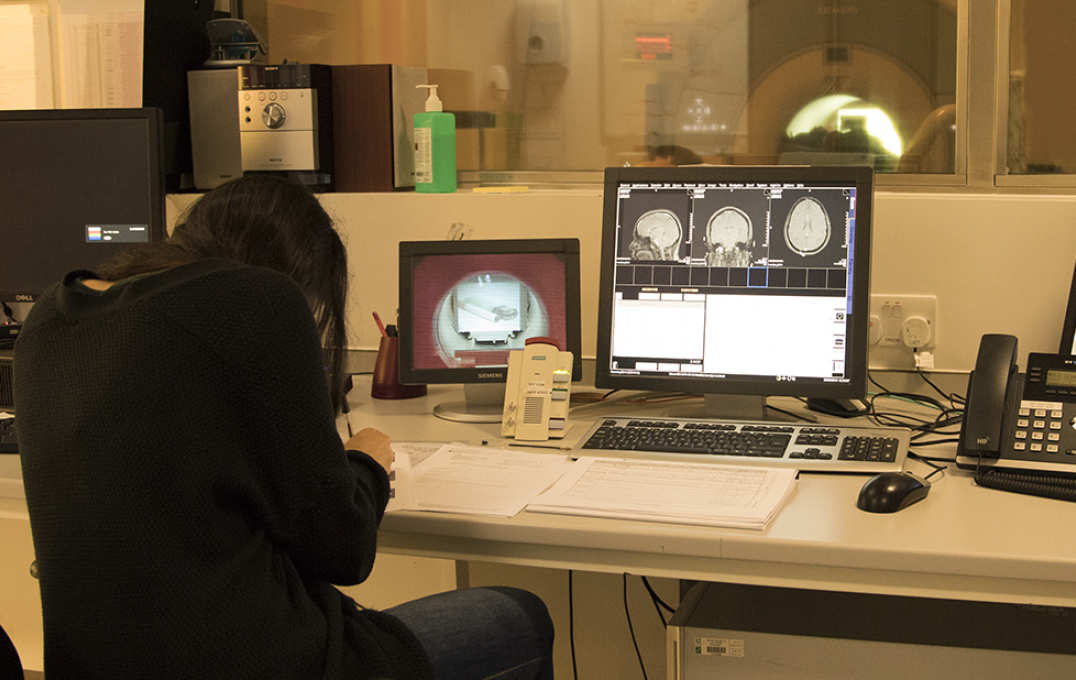

We will then ask them periodically throughout the day about how hungry they are, and how much they want a cigarette. We will also take blood samples to measure their hormone levels. About two hours following the start of the infusion, they undergo about an hour of brain scanning. We ask them to perform different tasks while they are in the scanner. Firstly, they look at a variety of different pictures of food, cigarettes and alcohol, and rate how appealing they find the images. This allows us to see whether the hormones reduce the response of the brain’s reward system. As the participants have only recently given up smoking, they may still crave cigarettes and respond positively to them.

The participant then takes part in a monetary incentive delay task. Here, they have to press a button very quickly in response to a cue in order to win or prevent the loss of money. This is a very good way of activating the brain’s reward system, and again allowing us to see whether the hormones have any effect on its responses.

The final activity is what we call an ‘unpleasant images task’. This is a way of testing how the brain responds to negative emotions. We know that one of the main reasons why people start smoking again – and also why they drink and overeat – is stress. We’re looking to see if these hormones will reduce how the brain responds to these unsettling triggers. Reducing stress response in the brain is another potential mechanism by which these hormones might help with smoking cessation.

Outside of the scanner, the participant will then perform some computer-based tasks. They play some games where we measure how quickly they can respond to prompts on the screen, which helps us to see whether the hormones inhibit repetitive actions.

At the end of the study, we give the participant different foods to taste and eat in order to assess their appetite, and to see whether we can reduce their food intake.

Beyond research, what other steps do you think need to be taken to stem the negative impact of smoking on public health?

We know that smoking remains one of the top global health issues. In this country, the restriction of smoking in public spaces has certainly made a huge impact. The prevalence of smoking is declining, but we still have a way to go.

There are big problems in the developing world, where smoking has a much higher prevalence than in this country Dr Tony Goldstone

Vaping has a lot of potential to help matters, although there has been some controversy about the possible risks associated with it. I think it needs to be made clear that any potential risks involved in vaping are significantly less than smoking tobacco. This is because vaping liquid contains nicotine but not tobacco, although there are some other substances in the liquid at low concentrations. Whatever the potential health concerns are about these other additives, they are likely to be considerably less harmful than the carcinogens found in tobacco.

Although there have been some controversial statements made by certain bodies about vaping, the general view held by the nicotine research community is that it has a big part to play in the reduction of risk and harm with smoking tobacco. I think that is what it has to be about: harm reduction, not trying to stop nicotine use altogether. It’s worth noting that vaping also has another benefit in allowing people to gradually reduce their use over time by self-adjusting the dose. There isn’t much evidence to suggest that nicotine by itself has any major detrimental effects. What we need to look out for is the tobacco industry’s involvement in the future of vaping; there are critical questions to be answered about whether they can actually help or be a hindrance.

Of course, we are just talking about how things are in the United Kingdom. There are big problems in the developing world, where smoking has a much higher prevalence than in this country, and we have a long way to go in this regard.

A recent US-based study revealed that the perceived risk of smoking had declined significantly between 2006 and 2015. Do you think that people in the UK have a good understanding of the risks involved in smoking?

I would hope that in this country, through the changes made to branding on cigarette packets, there is a good awareness. Of course, those that are still smoking are likely to be highly resistant to taking on board the risks, and perhaps understanding the full health implications.

I think that perhaps what hasn’t been successfully conveyed to the public is the benefits of stopping smoking. People think that, because they’ve smoked cigarettes for so long without seeing any immediately obvious negatives, there’s no point in stopping. However, within quite short periods of time after quitting smoking, the risks of heart disease and even of lung cancer can decline. Public health messaging tends to focus on the negative aspects, but the data about the benefits of quitting are generally under-reported and under-appreciated by the general public.

Another problem is that anecdote always trumps data, because we have a tendency to cling to our personal beliefs. Those beliefs, as we’ve learnt in recent political times, are very powerfully held, so breaking them down can be incredibly difficult. Trying to find an appropriate public health message that gets around this continues to be a real challenge.

If you are interested in learning more about the study or becoming a participant, please visit www.ghadd.co.uk.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Ms Genevieve Timmins

Academic Services