Bacteria can ‘divide and conquer’ to vanquish their enemies

Some bacteria can release toxins that provoke their neighbours into attacking each other, a tactic that could be exploited to fight infections.

Bacteria often engage in ‘warfare’ by releasing toxins or other molecules that damage or kill competing strains. This war for resources occurs in most bacterial communities, such as those living naturally in our gut or those that cause infection.

This behaviour is strongly reminiscent of the human ‘divide and conquer’ strategy. Dr Despoina Mavridou

As well as producing toxins that directly kill their competitors, bacteria can release toxins that can act as ‘provoking agents’. These provoking toxins make other strains increase their aggression levels by boosting their toxic response.

In a new study, led by Imperial College London and the University of Oxford and published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers used a combination of experiments and mathematical models to see what happens when bacteria provoke their competitors.

The art of bacterial war

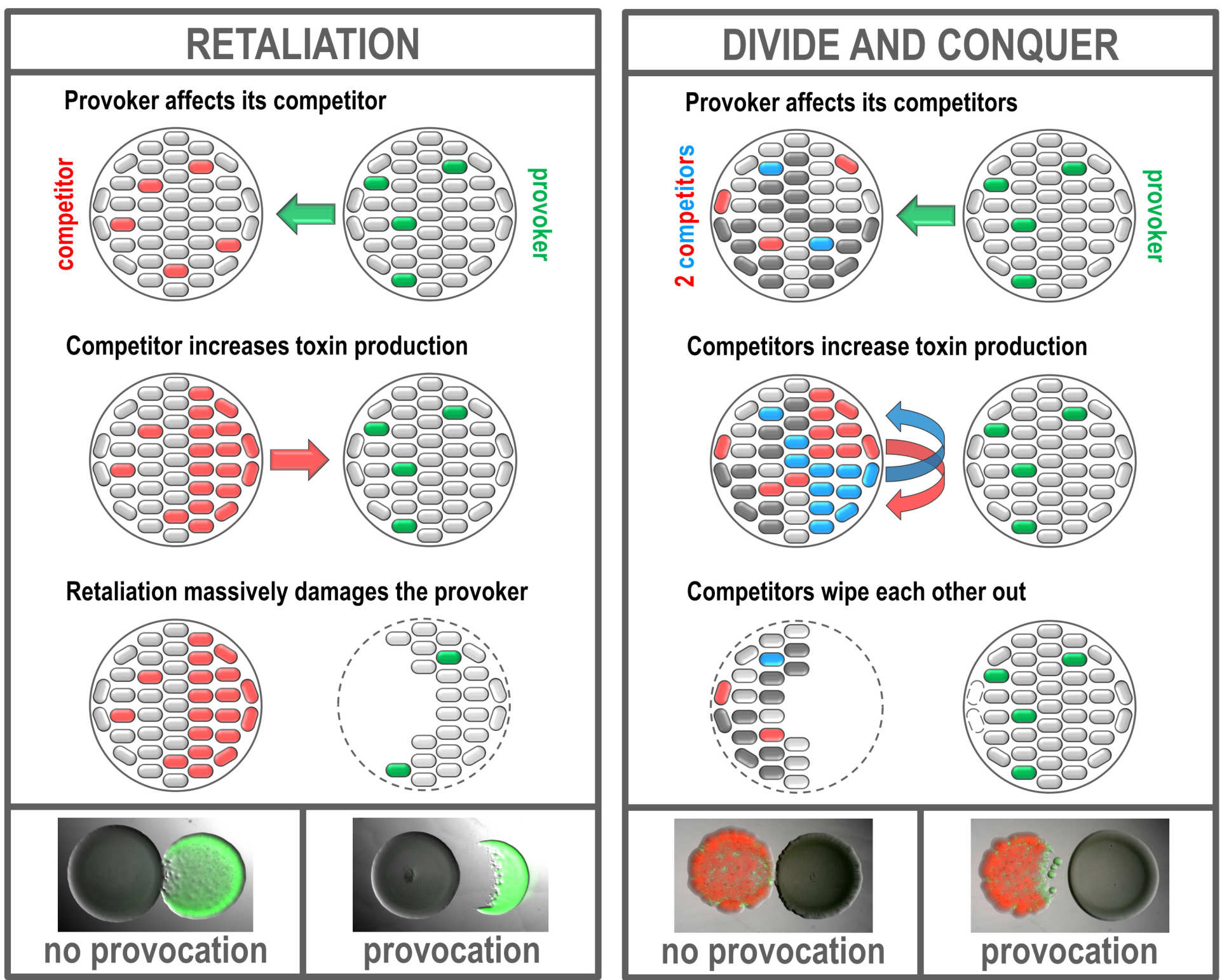

They found that when used against a single competitor, provocation backfires: the provoked strain mounts a strong toxic counterattack and harms the provoking strain.

However, when there are three or more strains present, provocation causes the other competing strains to increase their aggression and attack each other. This can lead to the competitors wiping each other out, especially when the provoking strain is shielded from, or resistant to, their toxins.

Senior author Dr Despoina Mavridou, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: “This behaviour is strongly reminiscent of the human ‘divide and conquer’ strategy, famously delineated by Niccolò Machiavelli in his book The Art of War and shows that bacteria are capable of very elaborate warfare tactics.”

Exploiting aggression

The researchers suggest that the strategy could be exploited to manipulate microbial communities. Lead author Dr Diego Gonzalez, from the University of Lausanne, said: “We could envisage exploiting provocation in alternative antimicrobial approaches. For example, exposing established bacterial communities to low levels of known antimicrobials could promote warfare and cross-elimination of different strains.”

This approach could be particularly useful to help eradicate resistant biofilms – layers of bacteria that form for example in industrial water pipes and are hard to remove. It could also be used to treat some bacterial infections if the composition of the bacterial community responsible for the infection is well known.

Dr Mavridou added: “By provoking other strains to attack each other, the toxin of the provoker is more effective than what would be expected based on its real toxicity. Using toxin-mimicking chemicals, we could potentially manipulate microbial aggression to our own benefit.”

The study’s other authors are Akshay Sabnis from the Medical Research Council Centre for Molecular Bacteriology and Infection at Imperial and Professor Kevin Foster from the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford.

Listen above to an audio report on the study (is listen to the whole episode of the Imperial College Podcast)

-

‘Costs and benefits of provocation in bacterial warfare’ by Diego Gonzalez, Akshay Sabnis, Kevin R. Foster, and Despoina A. I. Mavridou is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

-

Full image captions:

Retaliation: Toxin producers produce a small amount of toxin all the time (green and red cells). A provoking toxin-producer (right) is sensed through its released toxin by its competitor (left), which in turn becomes more aggressive by producing more toxin, causing significant damage to the provoker. The panels at the bottom show the difference in outcome when a strain is non-provoking (green colony, left panel) or provoking (green colony, right panel) against the same competitor (unlabelled colony in both panels).

Divide and conquer: A provoking toxin producer (right) is sensed through its released toxin by its competitors (left); the competitors are closer to one another than to the provoking strain. Provocation leads to increase in aggression in the competing mixed colony, but in this case the produced toxins wipe out the two competing strains while affecting the provoker less. The panels at the bottom show the difference in outcome when a strain is non-provoking (unlabelled colony, left panel) or provoking (unlabelled colony, right panel) against the same set of competitors (red/green colony in both panels).

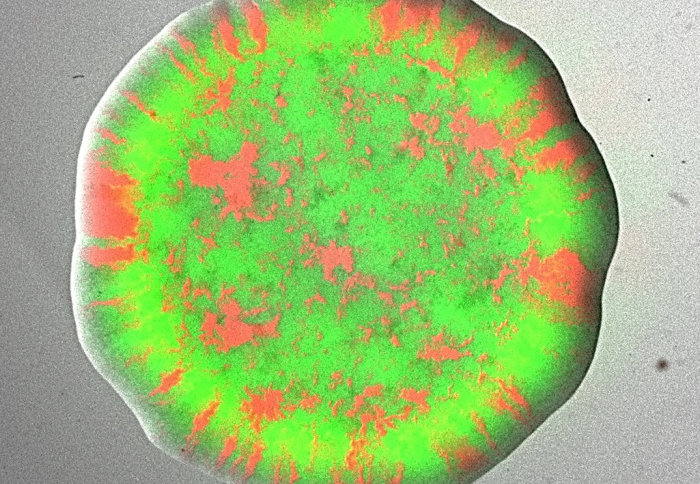

Bottom image: Provocation can be beneficial in mixed communities. Colonies consist of three toxin producers (red, green and unlabelled). The strain of interest (red toxin producer) is resistant to the toxins of its two competitors in both cases, but can take over the colony only if it can pit the two other strains against each other (right panel).

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division